One of the striking and sad things about the pandemic for me has been a disconnect between my own relatively uninterrupted experience and what I see as the broader, more traumatic experience. One of the key drivers of the more dramatic disparity is the technology that is being deployed in response to the pandemic.

In this essay, I will suggest a framework for teasing out the distribution of relative winners and losers resulting from the adoption of new technology. Using this framework, I’ll argue that COVID is accelerating the “virtualization” of the economy and that the adoption of new technology and norms like remote work, Zoom meetings, and delivery commerce will drive lumpier (power) distributions of earnings.

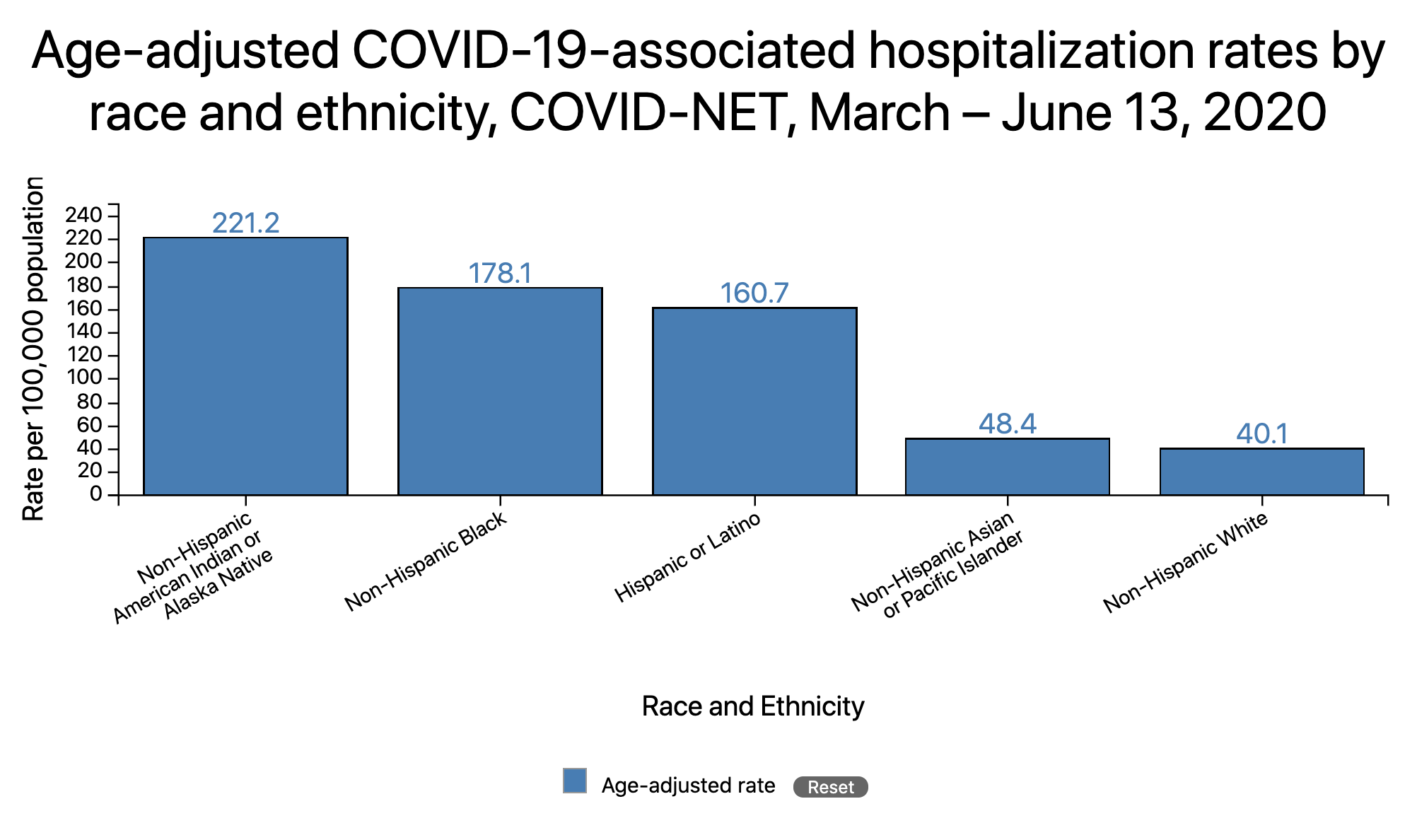

While this essay focuses on disparity in economic consequences, I want to acknowledge the disparity in health consequences of COVID.

The early numbers confirm that the impacts of COVID-19 are indeed very different for different populations – this report from the CDC estimates that the hospitalization rates are 4-5 times higher for Black, Hispanic, Latino, and American Indian people in the US vs whites:

This is a pretty long essay, so here is the tldr;

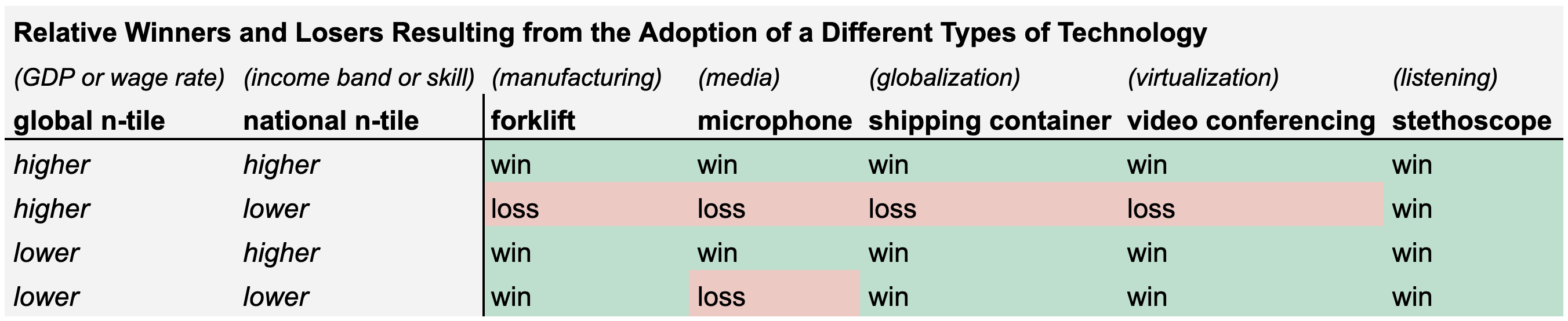

- We can extend the “microphone or forklift?” question from a 2007 Edward Leamer essay with a few more representative types – shipping container, video conferencing, stethoscope – to build a useful framework for thinking about the relative win/loss distributions of different kinds of new technology.

- As virtualization increases global competition for service work and knowledge work, the effects will mirror those of globalization, driving wages down by allowing jobs to move to geos / countries where labor is cheaper.

- As virtualization allows some local services to become “content,” the effects will mirror those of a “microphone technology,” resulting in superstar effects.

- Virtualization will benefit capital (owners of tech) and relatively favor labor in lower GDP countries / lower cost geos.

- One area where virtualization has the potential to create more jobs than it destroys is where it serves as a “stethoscope technology” that facilitates 1:1 listening.

Let’s dive in.

Setup: Forklifts and Microphones

In a 2007 essay in the Journal of Economics Literature, Edward Leamer asks the following question, which I think we can extend to build a framework that can help us understand the effects of any new type of technology (like virtualization).

“Is a computer more like a forklift or more like a microphone?”

Leamer goes on (emphasis mine, and I will quote at length rather than paraphrase):

It doesn’t matter much who drives the forklift, but it matters a lot who sings into the microphone. Think about the forklift first. You might be a lot stronger than I, but with a little bit of training, I can operate a forklift and lift just as much as you or any other forklift operator. Thus the forklift is a force for income equality, eliminating your strength advantage over me….

The effect of the microphone and mass media have been to allow a single talented entertainer to serve a huge customer base and accordingly to command enormous earnings. This creates an earnings distribution with a few extremely highly paid talented and trained individuals….

A computer is both a forklift and a microphone. Clerks in McDonalds no longer have to be able to read or to compute…. That’s the forklift. It doesn’t much matter who punches the buttons. Thus your intelligence advantage over me is eliminated by the computer, just as your strength advantage was eliminated by the forklift. But for many other operations it matters enormously who types on the computer. One example is computer programming. …. A talented architect with a computer assistant can serve a much enlarged customer base. A talented attorney, or a talented economist, or a talented radiologist with computer assistants can serve much enlarged customer bases. These talented individuals command high wages while the less talented struggle for customers.

Computer technology seems therefore to be taking us into a future where there are a few very talented, very well-paid people and the rest of us are doing the mundane computer-assisted tasks which don’t require us to read, write, or even think very much. Just push the right button now and then.

In other words, the information revolution may be a powerful force for income inequality by raising the compensation for natural talents and also the interaction between talent and training.

Now let’s extend some of his examples and dig a bit more into who wins and loses relatively when technology like a forklift has an “equalizing” effect.

Dispersion Patterns of Technology

When Leamer talks about the equalizing effect of a forklift, he talks about it as a sort of closed system – the technology is made available everywhere at once and facilitates competition across an entire population, which kind of makes it sound great for the lowest skilled workers in the population.

But I want to add a dimension to Leamer’s framework that considers not only your starting position within a country, but also the relative position of your country relative to other countries (ranked by per capita GDP, workers’ rights, cost of living, or anything else that correlates with cost of labor).

An example will help illustrate why this additional dimension matters.

Take the perspective of a national economy as a closed system – if you start off in one of the lower bands, the forklift might enable you to do a job you previously could not do, making you relatively better off than before.

Now, let’s consider the global perspective, and imagine you are this same person in a lower-ntile of the income distribution within your country. Add the extra dimension that you live in one of the higher GDP countries, so your initial position globally is better than that of someone with your same skills and job in one of the lower GDP countries. With this framing, even though the forklift levels the playing field within your own country, it also entails A LOT more competition for you from every other country, which means you’ll be relatively worse off globally (and, the workers in the lower GDP countries will be relatively better off).

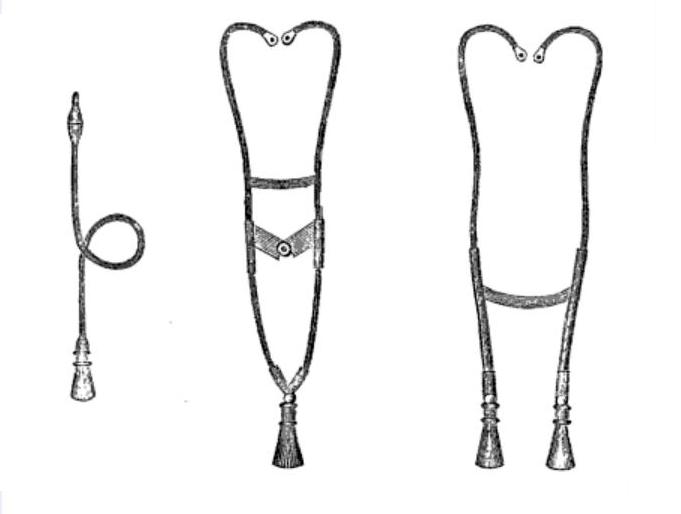

I have also added a few new technologies to Leamer’s forklift and microphone set (which I labeled as representatives of “manufacturing” and “media” respectively): shipping container for “globalization,” video conferencing for “virtualization,” and stethoscope for “listening.”

This little win / loss matrix provides a concise summary of the key technology trends afoot today:

A few notes:

- How I scored this is up for debate / somewhat speculative. I’m curious how others would score it differently.

- However you score it, I think the exercise demonstrates that all technologies do not benefit everyone equally.

- I have chalked up pretty much any new technology as a win for the capital class in any country, since they will typically either own related IP, earn a return on investment by provisioning the new technology, or extract rent if they control distribution, eg, in the case of media companies monetizing content.

full notes on how I scored my scorecard .............................................

- Forklift: high earners everywhere win because they own the tech, lower earners in higher GDP countries lose due to increased competition from lower earners in lower GDP countries (who relatively win).

- Microphone: a few superstars win big and can reach infinite audiences, consequently way fewer jobs (both singing and in related things like event production), the real winners are high earners in any country who own the distribution rights, technology, and relationships (eg, record labels, digital media companies).

- Shipping container: good for higher earners everywhere who own the containers, ships, distribution networks; good for lower earners in lower GDP countries when manufacturing is exported there, bad for lower earners in higher GDP countries because they lose manufacturing jobs.

- Video conferencing: good for high earners everywhere because it facilitates knowledge sharing and trade; good for lower n-tile / lower GDP workers when knowledge work is exported to them, bad for lower n-tile / higher GDP workers because they lose knowledge work jobs.

- Stethoscope: perhaps the most positive sum of all of these, least subject to monopoly / rents (tho you could argue that higher earners that own the tech benefit more than workers using the tech).

In the rest of this essay, I want to discuss the winners and losers posited in the “virtualization” column of this matrix.

Virtualization post-COVID as Globalization on Steroids

If adoption of virtualization technology resembles any other technological trend, I think it will be most similar to globalization, but on steroids.

Here are a few of my own personal observations and anecdotes how this is playing out during the pandemic.

The Shift to Remote Work via Zoom / Slack Will Stick

COVID has forced all firms who can virtualize to experiment with it, and the results have largely been positive. For desk jobs, the technology to support remote work has existed for quite awhile, but I think two things held back the shift to remote until now.

First, there was hesitation on the part of firms about losing the high bandwidth / low latency forms of communication afforded by physical proximity. Many at my own company (a small SAAS software business) were specifically skeptical about losing (1) water-cooler and lunch chats for unstructured / exploratory discussion, and (2) white-boarding and tapping people on the shoulder for resolving issues and questions immediately.

So far, in the short term, we have not missed these as much as we expected. If anything, net/net, our team is higher productivity than when in the office.

Another pre-COVID concern we had with remote work was that if we had most people in the office everyday and a few remote employees, this would give a relative advantage (in terms of being part of important conversations) for those in the office vs remote. Going FULLY remote (as the pandemic has forced everyone to do) makes this a non-issue, however. A friend who is a software engineer at Twitter in NYC confirmed this concern (and its mitigation), reporting that it was great for him when his company went fully remote, because it has levelled the playing field by forcing all conversations online and removing the option for important conversations to happen in-person at HQ in the Bay Area.

Another anecdote from a friend at a ‘unicorn’ pre-IPO tech company: many senior PMs and engineers have already moved out of the Bay Area to other low cost geos (Nashville, Montana)… BUT the dream of earning a Bay Area salary and working remote where cost of living is far cheaper is not materializing. Management has already anticipated the hack, and workers leaving the Bay Area are taking pay cuts.

This starts to touch on the key question I want to ask: if the shift toward virtualization and remote work sticks (which I suspect it will, tho WSJ and Nicholas Bloom think otherwise), who wins / loses relatively?

- Firms will lower their costs by employing workers in lower cost geos in the U.S.

- Firms could dramatically lower their costs further by employing workers in countries with a lower cost of labor.

- In short, increased intra- and inter- national competition for jobs that firms previously thought “must be in HQ” will put downward pressure on wages. (This will be great, eg, for software engineers in Ukraine.)

- Firms will lower the costs of having an office (real estate) and associated benefits (meals).

- All of these savings will be captured by firms, with few benefits (other than maybe reduction in commute times) accruing to workers.

- Real estate in hubs (like the Bay Area) – which arguably captured most of the higher wages anyway – will suffer.

Most of the virtualization technologies at play for desk work are fairly obvious: Zoom or Google Meet for video conferencing, Slack or Discord for group chat, etc.

One technology that I’ve been tracking that will intersect with these other virtualization trends in interesting ways is machine translation. Services like Unbabel are already used by large firms to enable service work to cross language barriers – workers who natively speak Thai can service requests from customers who only speak Spanish or Mandarin. This technology has already deployed for email and chat support, and it is likely that it will soon be ready to handle realtime phone support as well. This will dramatically change the shape of the labor supply for all sorts of service work (and pretty much any other type of knowledge work) by creating a lot more global competition for work that was once constrained by language barriers.

Virtualization of Services and Retail Will Favor Big Corporations (vs Mom and Pop, Local Businesses)

Speaking of service work, it is not just IT / desk jobs that will virtualize. All sorts of other local services that consumers were hesitant to virtualize – either because of nostalgia or fear of change or a desire to support local – are being forced to “go virtual” by government mandate.

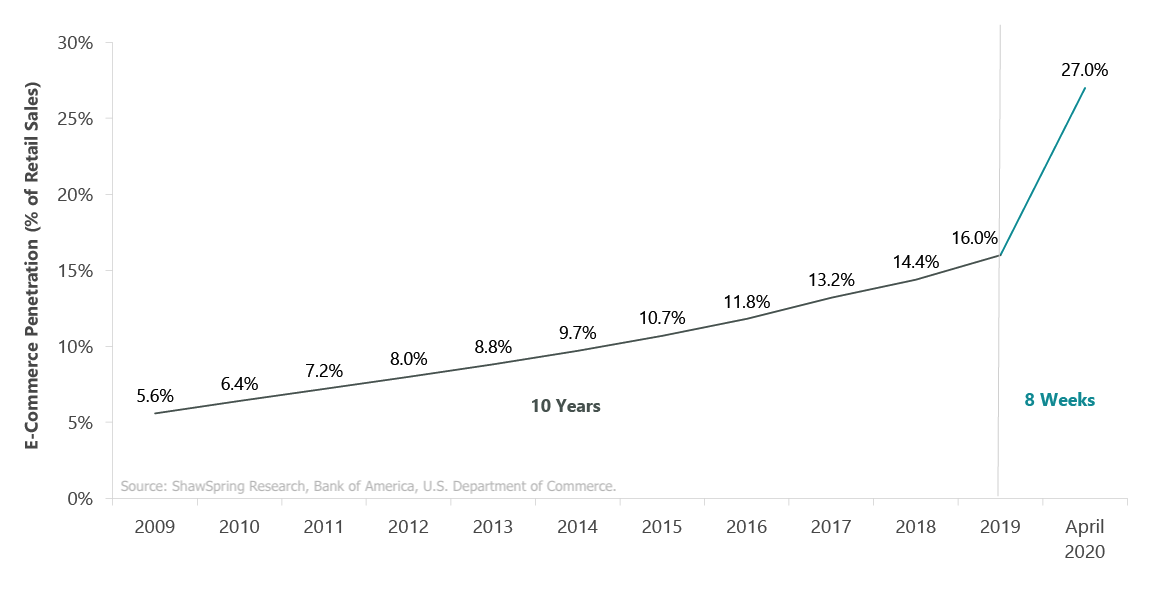

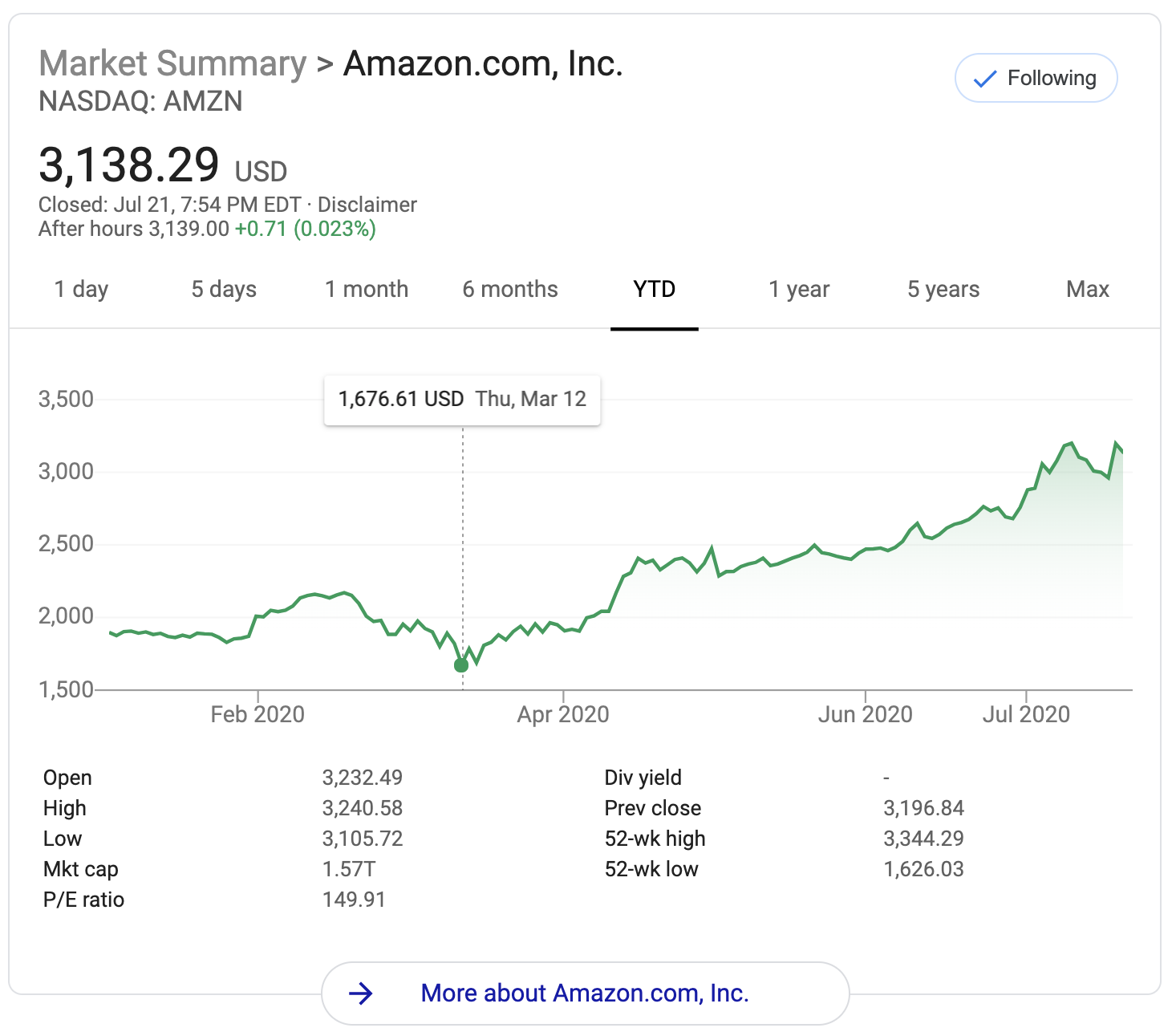

Many shoppers are trying out delivery and ecommerce during the pandemic – because they must:

Looking at my own behavior, before the pandemic, I was making a concerted effort to buy less on Amazon, because (1) I was starting to feel bad about all the cardboard boxes and (2) I was trying to shop more at local businesses, eg, buy produce from the local grocery co-op or farmers’ market, beer from the bodega down the street, etc.

Thanks to COVID, my Amazon purchasing has picked way up. And I’m cutting my own hair instead of going to a local barber, cutting my toenails instead of going for an occasional pedicure. I’m not going to local bars and restaurants at all (with the exception of ordering a pizza every once in a while).

All of this is really tough on small / local businesses.

With a lot of desk-work, the switching costs of virtualization were paid before the pandemic (most companies already had a lot of the software and process in place they needed to go remote – they just had to start fully using it). In the physical world, virtualization can be far more expensive and more difficult, especially for small / local businesses. Running an on-demand delivery network, eg for a grocery store or restaurant, requires a bunch of skills, technology, and a fleet of vehicles – and many mom-and pop businesses were just not set up with all of this going into the pandemic.

Even for a small business that has set up what it takes to virtualize, it is difficult to match the consumer experience that larger companies can provide. At scale, companies can stock inventory at local warehouses to minimize transport distance and minimize the cost of each trip by delivering to larger and denser sets of customers, so they can run more frequent deliveries and reduce shipping times. And, larger firms have stockpiles of cash and access to cheap debt they can use to weather months of low demand (cf the struggle of small businesses like Prune to just keep the lights on).

All of this – and a host of other scale efficiencies – make the accelerating adoption of e-commerce great for scaled players – eg Amazon, Instacart, Doordash – transferring market share to them, away from local grocery stores, restaurants, liquor stores, pharmacies, bodegas, pizza places, and the like.

Virtualization post-COVID as “Microphone Tech” on Steroids

While some of the effects of virtualization discussed above will resemble the effects of globalization, others will more closely resemble the effects of a “microphone technology.”

Here are a few other behaviors that have changed for me as a result of the pandemic:

- I have stopped going to local live music, theatre, and comedy.

- I have stopped going to local yoga studios, exercise and dance group classes.

- I have stopped going to the local gym, YMCA, and pool.

While I don’t have a Peloton bike, I did get their app a little over a year ago so I could do their treadmill workouts at my gym. Since the beginning of the pandemic, I have substituted outdoor runs for their treadmill workouts, but I have started using their yoga classes. I’m not sure I like any of the instructors quite as much as the teachers from my old studio, but in many ways the Peloton offering provides better ‘value’ than many studios:

- There are many different instructors and class types.

- There are many different lengths of classes (I used to love my NYC studio’s 60 minute class – an uncommonly short class – and I have actually been using the 30 min Peloton class quite a bit at home, which I would never do at a studio / is not even available at any studio I know).

- There’s no commute time to / from the studio – this is a huge time savings benefit.

- It’s way more cost effective, with an all-you-can-eat flat monthly fee of $13 / mo (vs $15 - $20 / class at a studio, or $150 - $200 / mo for an “unlimited” studio membership).

What I miss about the studio is the social element – seeing other students and bantering before and after class, giving a big hug to Brownie (the maternal woman who runs the kitchen at one of my favorite studios) whenever I see her, getting an occasional bit of personalized feedback from an instructor. But for most people, even though they will lose the social element, I think the convenience and dramatically lower cost will almost certainly make virtual yoga a better value than studio yoga. Post-pandemic, I know I’ll continue substituting virtual classes for at least some studio classes.

What does this mean in terms of winners and losers? Virtual yoga scales to infinite class sizes in a way that is not bounded by the limits of studio space, so there will likely be a lumpy distribution of winners, with a few superstar teachers growing massive audiences – perhaps a “Taylor Swift of yoga” will emerge out of India? And, fewer students will seek out local teachers near their homes or offices, making it hard for up-and-coming teachers or neighborhood studios to compete in the generic group class category of yoga.

Virtualization as Could also be a New and Massive “Stethoscope Tech” Opportunity

So, I’ve been thinking, how might you respond as a local yoga studio or teacher in light of all of this?

Sticking to our yoga example, let’s imagine a student who was taking 3 classes / wk @ $15 / class = $180 / mo. If they are now spending $15 / mo on an all-you-can-eat subscription to group (lecture style) classes, this frees up $165 / mo. Some might redirect this spend to an entirely different category of spending (or to savings), but some might have a fixed amount they want to spend on health / fitness activities – they might just have a ‘yoga budget’ in mind, or perhaps their employer offers some sort of “fitness stipend” reimbursement each month.

These latter might have newfound budget in the fitness category for something like private 1:1 instruction – which, by the way, could be far cheaper to deliver because transit to various 1:1 lessons comprises a large portion of the cost of service. And, perhaps there is a far larger market for a $50 private lesson than for a $150 private lesson. And, this is a service where it is difficult for a large market place to disintermediate the service providers (like say Zeel does for massage), because the 1:1 relationship between student and instructor that builds up over repeat lessons will build up important knowledge and personalization information that is not easily transferable.

Because it involves 1:1 listening, I think perhaps the appropriate representative for this job-creating kind of technology is the stethoscope.

Private yoga instruction is just one instance in this class of job that involves 1:1 listening that can easily crossover from physical to virtual delivery – some others, to name a few, are: tele-medicine, therapy, tutoring (vs lecture, in primary education), and probably a host of others I’m not thinking of at the moment – really, almost any kind of editing, proofreading, diagnostic, coaching, tutoring, or feedback could be done via virtual tête-à-tête instead of in-person.

And (to get uncharacteristically optimistic for a second) we could imagine how this sort of service economy reduces material waste. When mass production is cheap, fixing things is expensive, because it requires listening that doesn’t “scale” as efficiently as stamping out a brand new replacement on an assembly line.

When the chief problem for civilization is producing to satisfy basic needs in a world of scarce resources, not-scaling is bad. Given the pace of automation, more and more it looks like we are heading toward a world of abundant resources (at least those that satisfy basic needs), one where the chief scarce resource is good jobs. In such a world, jobs that “don’t scale” might be good, because they create demand for human labor.

The 1:1 listening roles enabled by ‘stethoscope’ technologies are exactly the type of labor that ‘scales’ in an important way for the next century – stethoscope tech is good at producing lots of jobs (as opposed to the ‘scale’ in producing goods that was historically more desirable).

“Industries” like childcare, healthcare (from fitness to nutrition to mental / psychological well-being), education, elderly care, and many others could all benefit from increased efficiency in 1:1 listening. All of these require lots of human attention.

How Virtualization Technology Can Accelerate Creation of 1:1 Listening Jobs

It’s fairly obvious how mass adoption of virtualization tech like video conferencing could facilitate this, but other trends could help as well – for example, the loosening of HIPAA regulation in response to COVID might stick and accelerate the shift to tele-medicine, and machine translation tools like Unbabel (mentioned above) could enable 1:1 listening across language barriers.

Another expensive / difficult aspect of 1:1 service that technology can make more efficient is scheduling and coordination (just try working as an executive assistant for a month if you have any doubts about the inefficiencies here). Technology can dramatically reduce time spent on the scheduling back-and-forth itself, and it can help increase utilization (schedulable slots filled).

One more area worth mentioning where technology can facilitate 1:1 virtual services is in the matching process. Navigating a market of millions of individual service providers presents a different challenge to consumers than choosing between a few name brands. But technology can make this problem tractable by providing matching and discovery algorithms and by aggregating reputation scores and ratings for service providers and for consumers (eg, a marketplace like Airbnb must aggregate reputation and reviews for hosts and guests in lieu of using a well-known, globo-brand promise and centralized operations to deliver a consistent customer experience the way Hilton can).

Sidebar: Big Data as Listening Tech?

This is an opportune time to digress on a sidebar asking whether or not big data aggregation will eliminate all of these 1:1 listening jobs.

In some cases, it probably will. For example, I have a friend who was experimenting with using synthetic data to train a machine vision algorithm to do yoga pose detection. While this algorithm is a long way from providing personalized feedback, it could be a first step in this direction. And in elite / professional athletics (eg, for baseball or golf swings), I’m sure coaching is already augmented by machine vision.

In other cases, big data is about an entire network – it’s not so much about listening to you (as a single node) as it is about analyzing all of the relationships (edges) in the network. The reputation data I mentioned above is a great example of this – fraud and trust data is the core value of any sort of online marketplace like Airbnb or Uber or Ebay or Venmo. The network data does not replace the knowledge of the service provider (eg, the driver or the host) but it facilitates the matching.

Because the compute and memory requirements of the algorithms running on these large data sets are beyond the power of any single human, it’s not quite a “stethoscope technology” – data aggregation often, therefore, doesn’t so much replace an existing job as it makes possible some new type of interaction.

This does not mean, however, that a handful of large corporations should capture the IP of data aggregation or network analysis – co-operative or public ownership of network data paired with decentralized approaches to compute on it (cf seti@home, bittorrent, blockchain) are better models, imho (but that’s a whole ‘nother essay).

Sidebar: Deep Fakes + Language Models as Listening Tech?

Perhaps a more likely candidate for supplanting human 1:1 listeners could be some combination of deep fakes with language models, which might be used to create lifelike avatars that pass the turing test holding conversation over a “video conference” interface.

These could be instantiated as new and personalized characters – “the perfect listener for you” / I want a sports coach that is part Bo Jackson, part Jackie Chan / I want a therapist that’s a cross between Terry Gross, Miranda July, and Albert Camus – or as reincarnations of dead friends and family…

The key questions here are:

- Does it really matter if your listener is human?

- Does it really matter if your listener is human if you don’t know they’re not human?

- Could you imagine being lonely enough that you change your mind about how much you care?

There are some cases already where maybe we don’t care if our listeners are human or not. I don’t mind getting “advice” from the Youtube and Spotify recommendation algorithms. And what could be more impersonal than the financial transaction between patient and therapist when compared to the conversation with a friend? Perhaps we have already answered some of these questions…

I sometimes think this is the case when I’m using Google search (especially via voice / Siri). The machine listens to my question and provides an answer. Unlike scrolling a feed or watching TV, it requires my active participation in the conversation.

Search is one of those technologies that can seem like all upside, costless. But recently I have been wondering what Google search means for grandparents. I often overhear Nam asking her parents for advice on all sorts of things - gardening, stocks, cooking, buying a car, etc. My natural inclination, in contrast, is to immediately consult Google or Youtube search when I encounter a novel task or problem.

How must our entire generation’s parents feel about this? Getting asked for advice by your adult children probably used to be a much more important source of meaning before Google, a way to feel (and be) useful as a retired empty-nester. (The “OK Google” / “OK Boomer” coincidence is just too sad to be ironic.)

Speaking of the psychological impacts of technological displacement, there’s one last form of listening to discuss – call it “witnessing.” Perhaps one of the deepest, most fundamental psychological needs we have as humans is to be heard, to have our existence (in a vast, cold and dark universe) acknowledged. When this need goes unmet, we suffer loneliness, depression, despair.

I heard recently that the former Surgeon General of the U.S. attributes America’s greatest epidemics – the opioid crisis and obesity – to loneliness, so technology that helps alleviate loneliness – whether it facilitates delivery by another human or delivers respite via an AI agent – probably can’t come too soon.

It may seem far more likely that AI agents will serve as listening advisors, coaches, or recommenders, and it may seem far more “sci-fi” that AI avatars will satisfy our needs for witnessing and alleviate our loneliness, but for a long time many people develop strong relationships with non-human creatures (dogs for example), so perhaps our incredulity at this notion is unfounded, the result of some sort of nostalgia.

The 2013 film Her takes this thread to its logical end – when a machine CAN satisfy your desire to be heard (and everyone else’s), does that leave your desire to BE A LISTENER for other humans unmet?

Conclusions

We’ve covered a lot of ground (probably digressed a bit tbh), so I’ll wrap things here with a few takeaways:

COVID will accelerate the virtualization of the economy. Virtualization will increase global competition for service work and knowledge work, driving wages down in many countries where this work happens today. Virtualization will also transform some local services into “content” businesses, resulting in “superstar” effects and making things tough for local, mom-and-pop businesses like yoga studios. One area where virtualization has the potential to create more jobs than it destroys is where it serves as a “stethoscope technology” that facilitates 1:1 listening.

In the end, the ultimate scarce resource in our civilization might be human attention, and the last job may be listening to or witnessing the experience of other lonely humans. Perhaps this is good news if your biggest concern is technological job displacement, because this kind of work fundamentally “does not scale” – so it will provision lots of jobs.