Pre

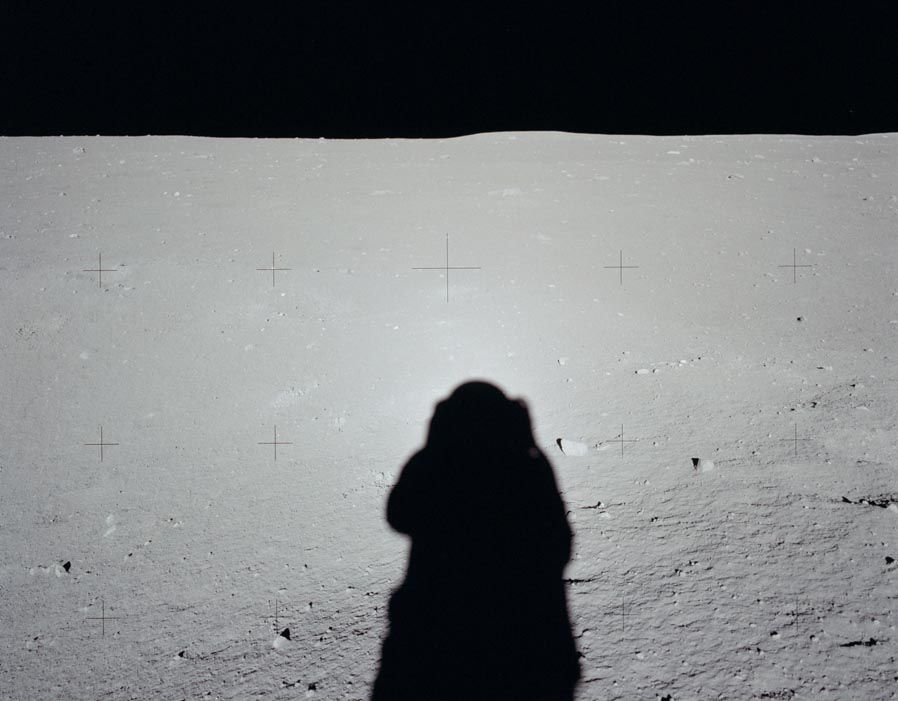

This movie has a certain ‘found’ aspect to it–that attribute of street art that I love. All of this beautiful footage of one of the coolest things that the human species has done was just sitting in the national archive for about 50 years, until a recent invention allowed them to scan and copy the original film without any risk of damaging it.

I first saw this movie at Sundance, and was pretty surprised that it did not pick up more distribution, so Sean and I are really excited to share it with a bunch of people today.

Post

There is a line in First Man–a dramatic film that tells the same story as Apollo 11–that really captures how I now think about the moon landing. Janet Armstrong tells NASA control:

You’re a bunch of boys making models out of balsa wood!

The comparison to “balsa wood” models does not feel far off, when you compare the tech of this NASA mission to what exists today–we have more powerful computers in our pockets than they used for this mission.

But the haunting–and perhaps more deeply true–element of this line is the implication that the whole thing is just a bunch of boys at play at a grand scale.

For The Emperor Has No Clothes, There is No Santa Claus, and Nothing is Rocket Science, I dug up the JFK speech responding to critics of the mission, articulating a justification for the endeavor:

But why, some say, the moon? Why choose this as our goal? And they may well ask why climb the highest mountain? Why, 35 years ago, fly the Atlantic? Why does Rice play Texas?

While JFK eventually lands on a sort of moral imperative argument about ensuring that the ‘good guys’ are first to unlock a new technological power, most of the speech has an existential tone, perhaps best captured in the comparison of the significance of the Apollo 11 mission to a college football game between Rice and Texas.

I love how subversive this idea is–you have the President of the United States and figurehead of pretty much all Western democracy talking about what will be one of the greatest accomplishments of the species–and, by the way, in retrospect, I think this is indeed one of the coolest things the species has ever done–and he reduces it to the same significance / insignificance as a college football game.

Space inspires awe, reminds us that all of the things that seem so big and important and meaningful to us reduce to a pale blue dot in space.

Last night I watched this movie Kung Fu Panda. The epiphany for the protagonist (spoiler alert!) is learning that his father’s soup has no secret ingredient, and that the ancient Dragon Scroll that is supposed to contain the ancient wisdom and secrets of the kung fu masters of history is blank.

Hearing JFK compare the Apollo 11 mission to a college football game is kind of a similar moment to learning that the message of the Dragon Scroll is “nothing.”

On the one hand, this is kind of earth shattering, because we want there to be something. We’ll seek out cruel and ancient masters in foreign and remote places and endure endless suffering in hopes that there is actually something that will be revealed after we have somehow earned the wisdom, and we really don’t want to believe that all the suffering was for nothing.

On the other hand, there is some sort of liberation in the meaninglessness. Instead of enduring for some sort of extrinsic reason–which no matter what it is, if it is extrinsic, can feel sort of obligatory, imposed, or even tyrannical–the meaninglessness gives us the freedom to choose to do the thing because we want to do it for it’s own sake. JFK makes this point, too, in his address:

We choose to go to the moon. We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win.

When I think of all the meaningless things I might do in life, being part of this Apollo 11 mission is one of the most sublime. The thrill of working with a team of people, drilling and dialing everything to the level of precision and excellence in execution required to pull this off must have been unparalleled.

This is why the denouement of this story, the return to Earth, and subsequent quarantine in an Airstream trailer, fascinates me.

It points to a danger in the celebration of the sublime–if you attach meaning to something like the Apollo 11 mission, what must every moment of your life after you have succeeded in this be like?

I am reminded of some bits from Mierle Laderman Ukeles’ Manifesto for Maintenance Art:

B. Two basic systems: Development and Maintenance. The sourball of every revolution: after the revolution, who’s going to pick up the garbage on Monday morning?

Development: pure individual creation; the new; change; progress; advance; excitement; flight or fleeing.

Maintenance: keep the dust off the pure individual creation; preserve the new; sustain the change; protect progress; defend and prolong the advance; renew the excitement; repeat the flight;

….

C. Maintenance is a drag; it takes all the fucking time (lit.)

The mind boggles and chafes at the boredom.

The culture confers lousy status on maintenance jobs = minimum wages, housewives = no pay.

clean your desk, wash the dishes, clean the floor, wash your clothes, wash your toes, change the baby’s diaper, finish the report, correct the typos, mend the fence, keep the customer happy, throw out the stinking garbage, watch out don’t put things in your nose, what shall I wear, I have no sox, pay your bills, don’t litter, save string, wash your hair, change the sheets, go to the store, I’m out of perfume, say it again—he doesn’t understand, seal it again—it leaks, go to work, this art is dusty, clear the table, call him again, flush the toilet, stay young.

This is Janet Armstrong’s critique, one I try to remember when I look back with awe on the achievement of the Apollo 11 mission: none of it matters / it’s all worth celebrating: the dish washings and fence mendings along with the moon landings.