Pre

I chose this, as I mentioned in the calendar invite, because it has some thematic relevance to the seminar Kortina and I are about to hold around narrative and computation. Since the role of narrative was a theme in the last two films, Ace in the Hole and Gaslight, it’s somewhat unintentionally also a continuation of that thread of film picks. I want to start with an excerpt from Kortina’s preamble from Gaslight, because it’s a sentiment that can also prime you for today’s film:

Over the past year or two, at what seems to be an accelerating rate, I’ve found a noir tinge to many of my own social interactions… A glance exchanged in the hallway, where you catch what you are sure is a look of utter despair in the eyes of your neighbor, like they have just been staring straight into the abyss and have not yet had time to compose themselves before your encounter… An offhand remark in casual conversation–a remark with innocuous intention, that was mistakenly uttered with a certain phrasing that gives it a grave and tragic significance that you are ninety-nine percent certain was recognized by all of the participants – all of whom, however, let the thing lie without any explicit acknowledgement… It’s as if everyone is taking great care to maintain the facade that until now you thought was just your own misperception.

My take on this in general is that: everyone knows; there are good reasons that no one should say; the conspiracy is essential. This is more or less what Kortina alluded to with his Fitzgerald quote, that a first rate intelligence is indicated by being able to keep deeply contradictory ideas in mind while retaining the ability to function, or Plato’s Noble Lie, or his favorite articulation: The madness of Sincerity. While this does resonate with me pretty deeply, it, for reasons alluded to in this film, is too misanthropic to me, despite my steadfast belief that misanthropy needs to be more deeply accommodated for. What’s more is that I think stories, symbols, and metaphors offer a much more resilient and workable model in certain cognitive niches than more concrete structural models, meaning and social conspiracy, being two notable ones. An articulation that I particularly like is that of the Ring of Mordor; You must bear it’s heavy and dark weight in order to make connections with the different types of people around you and to embark on things earnestly together, to integrate socially; if you put it on, you get super-powers but in a consuming, narrow, and destructive sense, so you must carry it, but carry it lightly. Or Cormac McCarthy’s more brief formulation, where a father repeatedly asks his son in the midsts of a wasteland: Are you carrying the fire?

Two other non-sequiturs:

..

Post

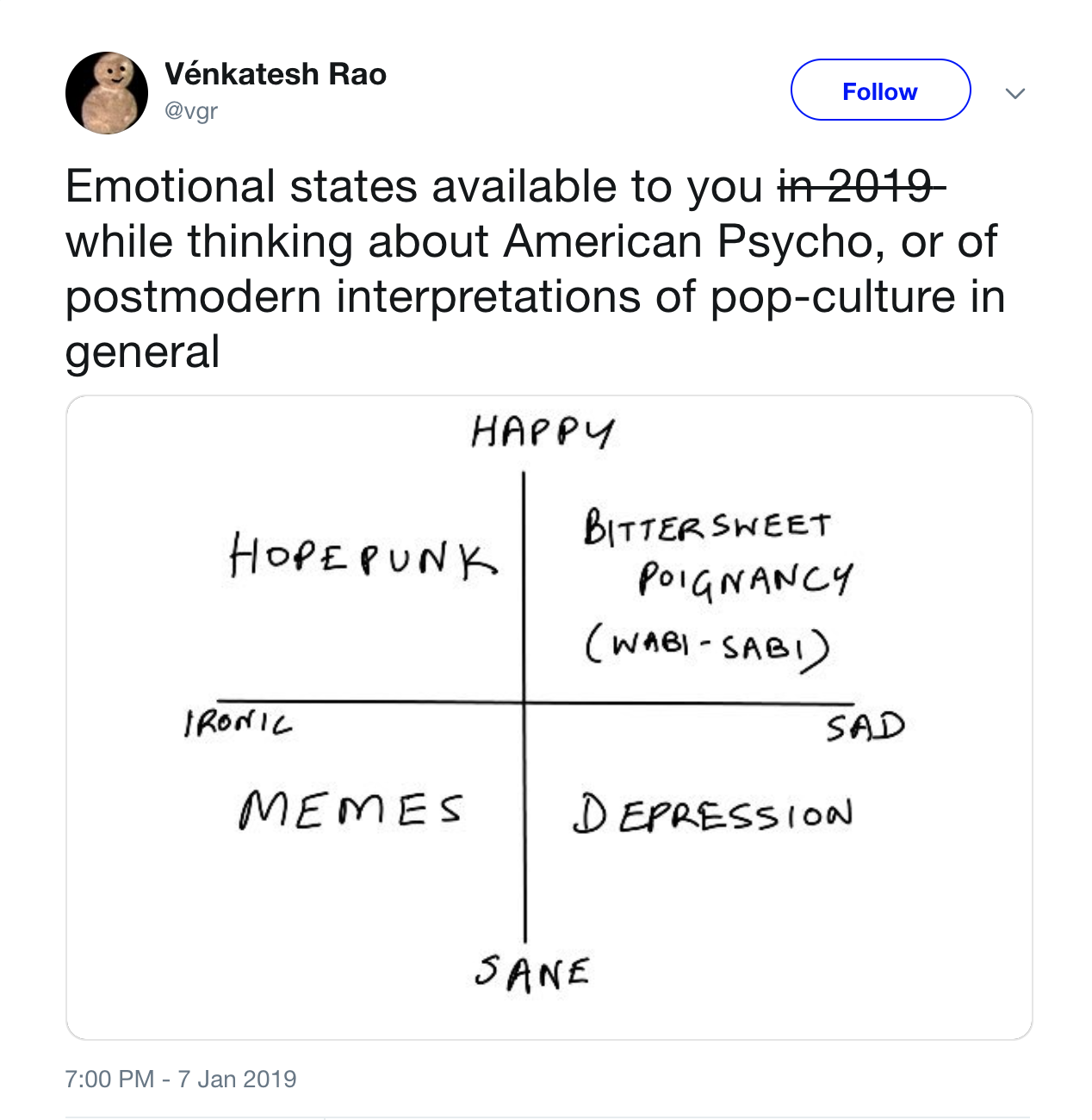

For those of you who don’t know, Venkat Rao is an internet blogger who focuses on writing essays to ‘refactor’ modern conceptions. Within this subculture, he’s known to use 2x2 matrices as a rhetorical device to explore possibility spaces, often in very insightful ways. It feels appropriate, despite the fact that I hate when people do this, that I make my next point with a cheap détournment of a subcultural symbol:

It’s a cheeky matrix for sure; you’re first impression of it is that it’s ironic since you’re expecting the axes to be labelled with duals, but they’re clearly not duals, but then you think about it for a second and see that it describes a pretty broad possibility space, and start to see how they might be duals. But now I’m hijacking the sentiment to apply it to the theme of this movie. While you’re in the headspace of the hyperreal, I think here it’s illustrative on different levels.

This is not a subtle movie; the themes aren’t subtle, the dialog is on the nose, the action sequences are graphic. It’s unabashedly an indulgent recapitulation of the postmodernist ideas. I won’t do an analysis of how Debord’s Spectacle, Barthes’ world of semiology, or Baudrillard’s simulacra are are repeatedly illustrated here. I mostly leave this as an exercise to the reader or viewer. It’s not that the issues are now irrelevant, they are not, it’s just that the problem space feels tired and stale. Reading postmodernist work, which I find to be a giant mass of abstruse language, is useful if you want to place a waypoint on your understanding of how Western thought has evolved, but I think modern Americans intuitively understand the issues that they present. If you want to get more of my or Kortina’s take on the sociological status quo, read our notes on narrative from the seminar.

Instead, as per usual, I’ll talk about oddities that came to mind mind when thinking about this film. To prep, I read the film’s screenplay. One thing that was surprising and slightly funny to me was the extent to which the screenplay’s text and stage directions made use of cultural references as a device for communicating a scene, and of course, how effective this was in communicating a scene. Given that this is a film that seems to indict modern life of being cultural simulacrum, it is obviously ironic; whether or not it’s intentional, who knows. Take for example a description of Bateman’s apartment:

A huge white living room with floor-to-ceiling windows looking out over Manhattan, decorated in expensive, minimalist high style: bleached oak floors, a huge white sofa, a large Baselitz painting (hung upside down) and much expensive electronic equipment. The room is impeccably neat, and oddly impersonal - as if it had sprung straight from the pages of a design magazine.

Call it indulgent screenwriting or bad filmmaking, but there are poetic elements in this screenplay that are hard to get across in cinematic cuts. Take this bit, from Patrick’s introduction sequence:

Bateman walks into his bathroom, urinates while trying to see his reflection in a poster for Les Miserables above his toilet.

And some notes from Hugo about what he intended to do with Les Miserable to really luxuriate in the poetic connection:

So long as there shall exist, by reason of law and custom, a social condemnation, which, in the face of civilization, artificially creates hells on earth, and complicates a destiny that is divine with human fatality; so long as the three problems of the age—the degradation of man by poverty, the ruin of women by starvation, and the dwarfing of childhood by physical and spiritual night—are not solved; so long as, in certain regions, social asphyxia shall be possible; in other words, and from a yet more extended point of view, so long as ignorance and misery remain on earth, books like this cannot be useless.

The book which the reader has before him at this moment is, from one end to the other, in its entirety and details … a progress from evil to good, from injustice to justice, from falsehood to truth, from night to day, from appetite to conscience, from corruption to life; from bestiality to duty, from hell to heaven, from nothingness to God. The starting point: matter, destination: the soul. The hydra at the beginning, the angel at the end.

Then the next lines from the screenplay:

There is an idea of a Patrick Bateman, some kind of abstraction, but there is no real me, only an entity, something illusory, and though I can hide my cold gaze and you can shake my hand and feel flesh gripping you and maybe you can even sense our lifestyles are probably comparable: I simply am not there.

And of course, it’s not just the metaphorical mirth you get from the thoughts of the Baselitz painting hung upside down or the virtual image of a symbolic man reflected at dull obfuscation of a bathroom poster about a story that embodies the platonic ideals that you miss out on without a reading since this type of story is a symbolic gold mine, something that’s made especially clear in written format where you have time to ruminate.

Poetry aside, usage of pop-cultural references in the screenplay comes off as extremely effective. David Foster Wallace in his ambitious essay E Unibus Pluram, constructs an argument about how the significance of television in western culture is understated. One of the mechanisms that he cites drives a cultural shift in psychology around how people communicate is the rise of pop references in media. He argues that this unprecedented rise in contemporary references as a rhetorical device is inextricably linked to how uniquely effective it is in a society that has consolidated both production and communication, and is itself ambivalent with fact that it has done so.

One of the most recognizable things about this century’s postmodern fiction was the movement’s strategic deployment of pop-cultural references - brand names, celebrities, television programs - in even its loftiest high-art projects. Think of just about any example of avant-garde U.S. fiction in the last twenty-five years, from Slothrop’s passion for Slippery Elm throat lozenges and his weird encounter with Mickey Rooney in Gravity’s Rainbow to “You”’s fetish for the New York Post’s COMA BABY feature in Bright Lights, to Don Delillo’s pop-hip characters saying stuff to each other like “Elvis fulfilled the terms of the contract. Excess, deterioration, self-destructiveness, grotesque behavior, a physical bloating and a series of insults to the brain, self-delivered.”[10]

The apotheosis of the pop in postwar art marked a whole new marriage between high and low culture. For the artistic viability of postmodernism is a direct consequence, again, not of any new facts about art, but of facts about the new importance of mass commercial culture. Americans seemed no longer united so much by common feelings as by common images: what binds us became what we stood witness to. No one did or does see this as a good change. In fact, pop-cultural references have become such potent metaphors in U.S. fiction not only because of how united Americans are in our exposure to mass images but also because of our guilty indulgent psychology with respect to that exposure. Put simply, the pop reference works so well in contemporary fiction because (1) we all recognize such a reference, and (2) we’re all a little uneasy about how we all recognize such a reference.

Thinking about this, it turned over some stones in my mind about an aspect of my taste in art. Particularly, I’ve known for a while that it’s usually tough for me to enjoy modern fiction I have very strong bias for the classics. When I read things by George Saunders, Bret Ellis, Jonathan Franzen, Thomas Pynchon, David Foster Wallace, etc, I almost always feel there’s some aesthetic hurdle I am making myself jump in enjoying them. I’m pretty sure that the cultural references play a role in this default distaste. I’ve said to a couple of people that one of my favorite aspects of travelling is that I don’t understand the advertisements and signs, and so feel a particular kind of cognitive freedom in foreign places. While I can’t deny the information density that signs carry, I have a default response to rage against cultural symbols, to opt-out of memes in many places where I can, because I recognize my vulnerability to the psychological trap of participation, most obviously with advertising where there is a clear misalignment of incentive, but the same clearly applies to general interpretations via popular opinion.

Part of the same paranoia I have around marketing, drives some of my default dislike of the entire branch of Pop Art. Richard Dawkins framed the situation well when he coined the term ‘meme’ in his book The Selfish Gene. There, he likens information encapsulated in cultural artifacts like conversation, books, and other media to genes, and makes the case that from an ecological perspective, the present distribution of cultural memes reflects a measure of fitness for replicability. It’s a distribution, that after many generations, can come to look something like intelligent design because the body of common memes seems largely so useful, but, he says, the top-down understanding is mistaken because the distribution is driven to competence without comprehension through bottom-up means of continuous global selection. Daniel Dennett pushed this idea further by recognizing that, much like viral genes, many primitive memes are very well suited for replication, but were mostly harmless and unuseful, just catchy in some way or another. But that today, there is a massive industry around creating, testing, and deploying effective memes; this is the marketing industry. Here’s a quote from my notes on narrative:

If marketing began as a set of methods and principles to articulate and sell a good to another individual, it has since, with scale and practice, transformed into something functionally different. Today marketing refers to something that serves a more general purpose; it is a process carried out by a social intelligence that tries to model and hack some aspect of the objective function for a separate targeted social intelligence by understanding some vulnerability common to all of the target group’s members. Marketing is the provision of an attack surface for corporate minds to hack bio minds.

Here’s Wallace again, with a similar sentiment:

For television’s whole raison is reflecting what people want to see. It’s a mirror. Not the Stendhalian mirror reflecting the blue sky and mud puddle. More like the overlit bathroom mirror before which the teenager monitors his biceps and determines his better profile. This kind of window on nervous American self-perception is just invaluable, fictionwise. And writers can have faith in television. There is a lot of money at stake, after all; and television retains the best demographers applied social science has to offer, and these researchers can determine precisely what Americans in 1990 are, want, see: what we as Audience want to see ourselves as. Television, from the surface on down, is about desire. Fictionally speaking, desire is the sugar in human food.

There are other things to be said about this movie re: schizophrenia, the duel between sincerity and fairness, and the movie’s ending (this is not an exit), but I will stop here for now. ..