Mariana Mazzucato’s The Value of Everything is part critique of the ‘financialization’ of all modern institutions and part history of the theory of value. What I found most interesting about this book were not any of the specific recommendations Mazzucato suggests for rescuing the economy, but her elucidation of many of the basic premises and assumptions that underly many of the most fundamental measures we have of economic health of nations (eg, GDP).

Here are some of the bits I particularly enjoyed:

This idea of the ‘production boundary’ separating productive from unproductive activity was something I either (i) had never learned about or (ii) had forgotten about. In any case, it is an important concept, in this book, and also more generally to keep in mind as a key assumption that undergirds a lot of policy:

To understand how different theories of value have evolved over the centuries, it is useful to consider why and how some activities in the economy have been called ‘productive’ and some ‘unproductive’, and how this distinction has influenced ideas about which economic actors deserve what — how the spoils of value creation are distributed.

For centuries, economists and policymakers — people who set a plan for an organization such as government or a business — have divided activities according to whether they produce value or not; that is, whether they are productive or unproductive. This has essentially created a boundary — the fence in Figure 1 below — thereby establishing a conceptual boundary -sometimes referred to as a ‘production boundary’ — between these activities.16 Inside the boundary are the wealth creators. Outside are the beneficiaries of that wealth, who benefit either because they can extract it through rent-seeking activities, as in the case of a monopoly, or because wealth created in the productive area is redistributed to them, for example through modern welfare policies. Rents, as understood by the classical economists, were unearned income and fell squarely outside the production boundary. Profits were instead the returns earned for productive activity inside the boundary.

Historically, the boundary fence has not been fixed. Its shape and size have shifted with social and economic forces. These changes in the boundary between makers and takers can be seen just as clearly in the past as in the modern era. In the eighteenth century there was an outcry when the physiocrats, an early school of economists, called landlords ‘unproductive’. This was an attack on the ruling class of a mainly rural Europe. The politically explosive question was whether landlords were just abusing their power to extract part of the wealth created by their tenant farmers, or whether their contribution of land was essential to the way in which farmers created value.

A brief history of the production boundary:

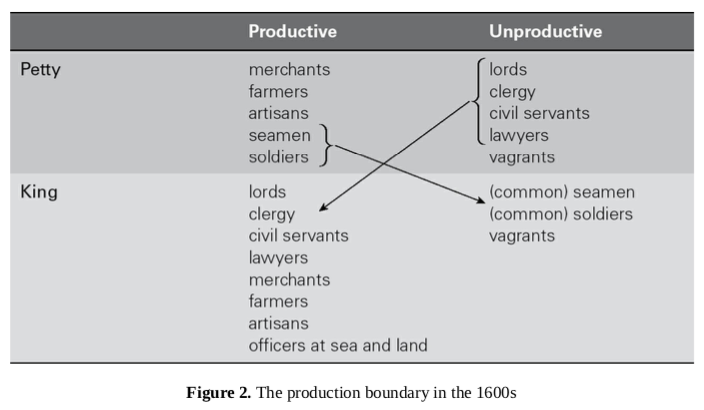

For Sir William Petty (1623–87), productive activity included only “the production of ‘Food, Housing, Cloaths, and all other necessaries’,” with

‘Husbandmen, Seamen, Soldiers, Artizans and Merchants … the very Pillars of any Common-Wealth’ on one side; and ‘all the other great Professions’ which ‘do rise out of the infirmities and miscarriages of these’ on the other. By ‘great professions’ Petty meant lawyers, clergymen, civil servants, lords and the like. In other words, for Petty some ‘great professions’ were merely a necessary evil — needed simply for facilitating production and for maintaining the status quo — but not really essential to production or exchange. Although Petty did not believe that policy should be focused on controlling imports and exports, the mercantilists influenced him heavily. ‘Merchandise’, he argued, was more productive than manufacture and husbandry; the Dutch, he noted approvingly, outsourced their husbandry to Poland and Denmark, enabling them to focus on more productive ‘Trades and curious Arts’. England, he concluded, would also benefit if more husbandmen became merchants.

Gregory King (in the 1690s) deemed productive work anything where income was greater than expenditure.

As in Petty’s work, an implicit production boundary began to emerge when King thought merchant traders were the most productive group, their income being a quarter more than their expenditure, followed by the ‘temporal and spiritual lords’, then by a variety of prestigious professions. On the boundary were farmers, who earned almost no more than they spent. Firmly on the ‘unproductive’ side were seamen, labourers, servants, cottagers, paupers and ‘common soldiers’. In King’s view, the unproductive masses, representing slightly more than half the total population, were leeches on the public wealth because they consumed more than they produced.

via The Value of Everything, Mazzucato.

Francois Quesnay (1694–1774), a physiocrat, believed the earth was the source of all value, hence only trades that drew value from the earth were productive:

via The Value of Everything, Mazzucato.

Francois Quesnay (1694–1774), a physiocrat, believed the earth was the source of all value, hence only trades that drew value from the earth were productive:

Contrasting sharply with the prevailing mercantilist thinking that gave gold a privileged place, Quesnay believed that land was the source of all value. Figure 3 illustrates how for him, in the end, everything that nourished humans came from the earth. He pointed out that, unlike humans, Nature actually produced new things: grain out of small seeds for food, trees out of saplings and mineral ores from the earth from which houses and ships and machinery were built. By contrast, humans could not produce value. They could only transform it: bread from seeds, timber from wood, steel from iron. Since agriculture, husbandry, fishing, hunting and mining (all in the darker blob in Figure 3) bring Nature’s bounty to society, Quesnay called them the ‘productive class’. By contrast, he thought that nearly all other sectors of the economy — households, government, services and even industry, lumped together in the lighter blob — were unproductive.

via The Value of Everything, Mazzucato.

Quesnay’s contemporary** ARJ Turgot** expanded upon Quesnay’s theory of value, adding that artisans were productive because they helped refined products of the land:

via The Value of Everything, Mazzucato.

Quesnay’s contemporary** ARJ Turgot** expanded upon Quesnay’s theory of value, adding that artisans were productive because they helped refined products of the land:

Other economists quickly weighed in with analysis and criticism of Quesnay’s classification. Their attack centred on Quesnay’s labelling of artisans and workers as ‘sterile’: a term that served Quesnay’s political ends of defending the existing agrarian social order, but contradicted the everyday experience of a great number of people. Refining Quesnay’s thinking, his contemporary A. R. J. Turgot retained the notion that all value came from the land, but noted the important role of artisans in keeping society afloat. He also recognized that there were other ‘general needs’ that some people had to fulfil — such as judges to administer justice — and that these functions were essential for value creation. Accordingly, he re-labelled Quesnay’s ‘sterile’ class as the ‘stipendiary’, or waged, class. And, since rich landowners could decide whether to carry out work themselves or hire others to do so using revenues from the land, Turgot labelled them the ‘disposable class’. He also added the refinement that some farmers or artisans would employ others and make a profit. As farmers move from tilling the land to employing others, he argued, they remain productive and receive profits on their enterprise. It is only when they give up on overseeing farming altogether and simply live on their rent that they become ‘disposable’ rent collectors. Turgot’s more refined analysis therefore placed emphasis on the character of the work being done, rather than the category of work itself.

Turgot’s refinements were highly significant. In them, we see the emergent categories of wages, profits and rents: an explicit reference to the distribution of wealth and income that would become one of the cornerstones of economic thought in the centuries to come, and which is still used in national income accounting today. Yet, for Turgot, land remained the source of value: those who did not work it could not be included in the production boundary.

Adam Smith (1723–90), David Ricardo (1772–1823) and Karl Marx (1818–83), the classical economists, saw value not in land, but in labor:

Smith, Ricardo and others of the time became known as the ‘classical’ economists. Marx, a late outrider, stands somewhat apart from this collective description. The word ‘classical’ was a conscious echo of the status given to writers and thinkers of the ancient Greek and Roman worlds, whose works were still the bedrock of education when the term ‘classical economics’ began to be used in the later nineteenth century. The classical economists redrew the production boundary in a way that made more sense for the period they lived in: one which saw the artisan-craft production of the guilds still prominent in Smith’s time give way to the large-scale industry with huge numbers of urban workers — the proletariat — that Marx wrote about in the third quarter of the nineteenth century.…. Although their theories differed in many respects, the classical economists shared two basic ideas: that value derived from the costs of production, principally labour; and that therefore activity subsequent to value created by labour, such as finance, did not in itself create value.

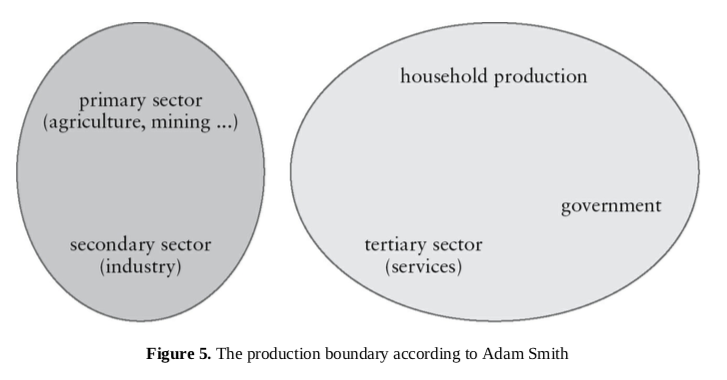

**Smith **drew the production boundary around physical production:

Value, Smith believed, was proportional to the time spent by workers on production. For the purposes of his theory, Smith assumed a worker of average speed. Figure 5 shows how he drew a clear line (the production boundary) between productive and unproductive labour. For him, the boundary lay between material production — agriculture, manufacturing, mining in the figure’s darker blob — and immaterial production in the lighter blob. The latter included all types of services (lawyers, carters, officials and so on) that were useful to manufactures, but were not actually involved in production itself. Smith said as much: labour, he suggested, is productive when it is ‘realized’ in a permanent object.25 His positioning of government on the ‘unproductive’ side of the boundary set the tone for much subsequent analysis and is a recurring theme in today’s debates about government’s role in the economy, epitomized by the Thatcher-Reagan reassertion in the 1980s of the primacy of markets in solving economic and social issues.

In Smith’s view, ‘how honourable, how useful, or how necessary soever’ a service may be, it simply does not reproduce the value used in maintaining (feeding, clothing, housing) unproductive labourers. Smith finds that even ‘the sovereign’, together with ‘all the officers both of justice and war who serve under him, the whole army and navy, are unproductive labourers’. Priests, lawyers, doctors and performing artists are all lumped together as unproductive too.

via The Value of Everything, Mazzucato.

Smith on three types of income — wages, profits, and rents:

via The Value of Everything, Mazzucato.

Smith on three types of income — wages, profits, and rents:

His emphasis on investment linked directly to his ideas about rent. Smith believed that there were three kinds of income: wages for labour in capitalist enterprises; profits for capitalists who owned the means of production; and rents from ownership of land. When these three sources of income are paid at their competitive level, together they determine what he called the ‘competitive price’. Since land was necessary, rent from land was a ‘natural’ part of the economy. But that did not mean rent was productive: ‘the landlords, like all other men, love to reap where they never sowed and demand a rent [from the earth] even for its natural produce’. Indeed, Smith asserted, the principle of rent from land could be extended to other monopolies, such as the right to import a particular commodity or the right to plead at the bar. Smith was well aware of the damage monopolies could do. In the seventeenth century, a government desperate for revenue had granted — often to well-placed courtiers — an extraordinary range of monopolies, from daily necessities such as beer and salt to mousetraps and spectacles. In 1621 there were said to be 700 monopolies, and by the late 1630s they were bringing in £100,000 a year to the Exchequer.30 But this epidemic of rent-seeking was deeply unpopular and was choking the economy: more than that, it was one of the proximate causes of the Civil War, which led to the execution of Charles I. Many Englishmen understood what Smith meant when he said that a free market was one free of rent.

Mazzucato points out an inconsistency in Smith’s theory of value (specifically calling into question the material/immaterial output line):

In essence, Smith was confused about the distinction between material and immaterial production. For Smith, as we have seen, a servant ‘adds’ no value that could be used by the master on something other than, literally, keeping the servant alive. But he also argued that if a manufacturing worker earns £1 in turning a quantity of cotton, whose other inputs also cost £1, into a piece of cloth that sells for £3, then the worker will have repaid his service and the master has made a profit of £1. Here a definition of productivity, irrespective of whether what is produced is a solid product or a service, emerges. Adding value in any branch of production is productive; not adding value is unproductive. Following this definition, services such as cleaning or vehicle repair can be productive -thereby invalidating Smith’s own material-immaterial division of the production boundary. The debates about Smith’s theories of value rumbled on for centuries. Other of Smith’s ideas, such as free trade and the unproductive nature of government, have also left an enduring legacy.

Ricardo defines rent:

Ricardo defined rent as a transfer of profit to landlords simply because they had a monopoly of a scarce asset. There was no assumption, as in modern neoclassical theory (reviewed in Chapter 2), that these rents would be competed away. They remained due to power relationships inherent in the capitalist system. In Ricardo’s time much of the arable land was owned by aristocrats and landed gentry but worked by tenant farmers or labourers. Ricardo proposed that the rent from more productive land always goes to the landlord because of competition between tenants. If the capitalist farmer — the tenant — wants to hang on to the largest possible profit by paying less rent, the landlord can give the lease to a competing farmer who will pay a higher rent and therefore be willing to work the land for only the standard profit. As this process goes on, land of increasingly poor quality will be brought into production, and a greater portion of the income will go to the landlords. Ricardo predicted that rents would rise.

Ricardo on distribution of the proceeds of production:

By highlighting the different types of incomes earned, such as rent, profits and wages, Ricardo drew attention to an important question. When goods are sold, how are the proceeds of that sale divided? Does everyone involved get their ‘just share’ for the amount of effort they put into production? Ricardo’s answer was an emphatic ‘No’.

If some input into production — such as good arable land — is scarce, the cost of producing the same output — a given quantity of corn — will vary according to availability of the input. The cost is likely to be lower with good land, higher with inferior land. Profits, instead, are likely to be higher with good land and lower with inferior land. The owner of good land will pocket the difference in profit between the good land and inferior land simply because he or she has a monopoly of that asset.38 Ricardo’s theory was so convincing that it is, in essence, still used today in economics to explain how rents work.39 Rents in this sense could mean a patent on a drug, control of a rare mineral such as diamonds, or rents in the everyday sense of what you pay a landlord to live in a flat. In the modern world, oil producers like those of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) collect rents from their control of an essential resource.

….

Here Ricardo made a fundamental point about consumption, by which he means consumption by capitalists, not just households. As with production, consumption can be productive or unproductive. The productive kind might be a capitalist who ‘consumes’ his capital to buy labour, which in turn reproduces that capital and turns a profit. The alternative — unproductive consumption — is capital spent on luxuries that do not lead to reproduction of that capital expenditure. On this matter, Ricardo is absolutely clear: ‘It makes the greatest difference imaginable whether they are consumed by those who reproduce, or by those who do not reproduce another value.’43

So Ricardo’s heroes are the industrial capitalists, ‘those who reproduce’, who can ensure that workers subsist and generate a surplus that is free for the capitalist to use as he or she sees fit. His villains are those ‘who do not reproduce’ — the landed nobility, the owners of scarce land who charge very high rents and appropriate the surplus.44 For Ricardo, capitalists would put that surplus to productive use, but landlords — including the nobility — would waste it on lavish lifestyles. Ricardo echoes Smith here. Both had seen with their own eyes the extravagance of the aristocracy, a class which often seemed better at spending money than making it and was addicted to that ultimate unproductive activity — gambling. But Ricardo parted company from Smith because he was not concerned about whether production activities were ‘material’ (making cloth) or ‘immaterial’ (selling cloth). To Ricardo, it was more important that, if a surplus was produced, it was consumed productively.

Marx and exchange as the source of value:

If commodities are exchanged — sold — they are said to have an exchange value. If you produce a commodity which you consume yourself it does not have an exchange value. Exchange value crystallizes the value inherent in commodities.

The source of that inherent value is the one special commodity workers own: their labour power, or — put another way — their capacity to work. Capitalists buy labour power with their capital. In exchange, they pay workers a wage. Workers’ wages buy the commodities such as food and housing needed to restore a worker’s strength to work. In this way, wages express the value of the goods that restore labour power.

via The Value of Everything, Mazzucato.

via The Value of Everything, Mazzucato.

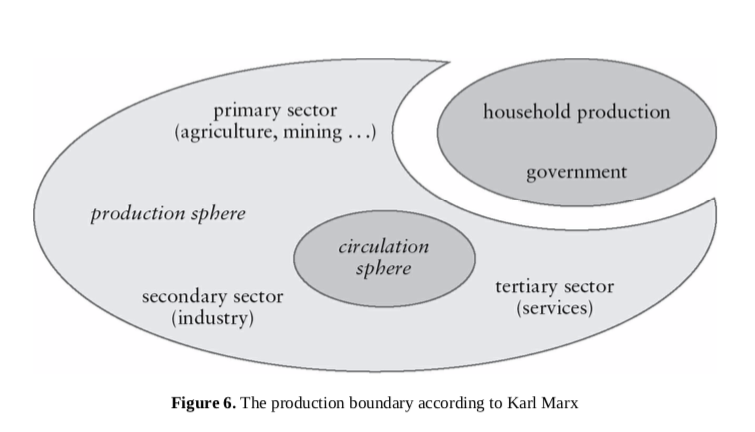

Marx refined Adam Smith’s distinction between productive (industry) and unproductive (services) sectors into something much more subtle. As can be seen in Figure 6, in Marx’s theory of value every privately organized enterprise that falls within the sphere of production is productive, whether it is a service or anything else. Here, Marx’s achievement was to move beyond the simple categorization of occupations and map them onto the landscape of capitalist reproduction. Marx’s production boundary now runs between goods and services production on one side and all those functions of capital that were not creating additional surplus value, such as interest charged by moneylenders or speculative trading in shares and bonds, on the other. Functions lying outside the production boundary take a chunk of surplus value in exchange for circulating capital, providing money or making possible surplus (monopoly) profits.

What is more, in distinguishing between different types of capitalist activity — production, circulation, interest-bearing capital and rent — Marx offers the economist an additional diagnostic tool with which to examine the state of the economy. Is the sphere of circulation working well enough? Is there enough capacity to bring capital to the market, so that it can be exchanged and realize its value and be reinvested in production? What proportion of profits pays for interest, and is it the same for all capitalists? Do scarce resources, such as ‘intellectual’ ones like patents on inventions, create advantageous conditions for producers with access to them and generate ‘surplus profits’ or rents for those producers?

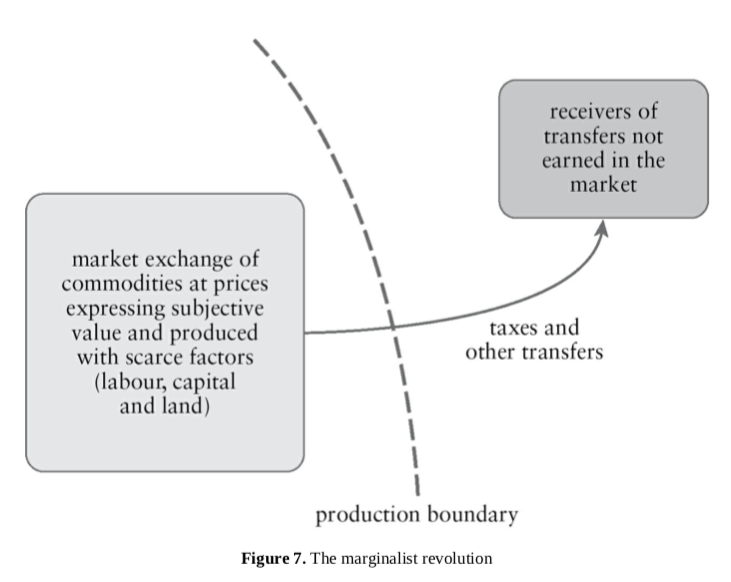

The neoclassical / marginal utility theory economists: Leon Walras (1834–1910), William Stanley Jevons (1835–82), Carl Menger (184-1921), Alfred Marshall (1842–1924) on ‘the mechanics of utility and self-interest’

The ‘marginal revolutionaries’, as they have been called, used marginal utility and scarcity to determine prices and the size of the market. In their view, the supply and demand of scarce resources regulates value expressed in money. Because things exchanged in a monetary market economy have prices, price is ultimately the measure of value. This powerful new theory explained how prices were arrived at and how much of a particular thing was produced.9 Competition ensures that the ‘marginal utility’ of the last item sold determines the price of that commodity. The size of the market in a particular commodity — that is, the number of items that need to be sold before marginal utility no longer covers the costs of production — is explained by the scarcity, and hence price, of the inputs into production. Price is a direct measure of value. We are, then, a long way from the labour theory of value.

via The Value of Everything, Mazzucato.

Now, Mazzucato gets to the crux of why these differing theories of value matter today:

via The Value of Everything, Mazzucato.

Now, Mazzucato gets to the crux of why these differing theories of value matter today:

In the subjective marginalist’s approach, wages, profits and rent, along with wages and profits, all arise from ‘maximizing’: individuals maximizing utility and firms maximizing profits. Thus labour, capital and land are input factors on the same footing. The distinction between social classes, including who owns what, is obliterated, since whether one lends out capital or works for wages depends on an unexplained initial endowment of resources.

Wages are determined by the worker equalizing the (diminishing) marginal utility of the money obtained from working with the ‘disutility’ of working, for example less leisure time. At the prevailing wage rate, the amount of time spent on work determines the income. This assumes that the amount of employment can be flexibly adjusted. If this is not the case, the marginal utility of taking a job might become less than the utility derived from an equivalent time of leisure; someone chooses not to work. As we have seen, this means that unemployment is therefore voluntary.

Profits and rent are thus determined analogously: the owners of capital (money) will lend it until the marginal utility from doing so is lower than that of consuming their capital. Landlords do the same with their land. For instance, the owner of a house might rent it out and then decide to let her daughter live there for nothing, effectively consuming capital because rent earnings are forgone. The justification for any profits is thus related to individual choices (based on psychology) and the psychological assumption that people derive less utility from future consumption (discounting). So the return on capital and land is seen as compensation for future marginal utility at a level which could be enjoyed today if the capital were consumed instead of lent.

In classical economics, therefore, rents are part of the ‘normal’ process of reproduction. In neoclassical economics, rents are an equilibrium below that which is theoretically possible — ‘abnormal’ profits. The main similarity is that both theories see rent as a type of monopoly income. But rent has a very different status in the two approaches. Why? Chiefly because of the divergent value theories: classical economics fairly clearly defines rent as income from non-produced scarce assets. This includes, for example, patents on new technologies which — once produced — need not be reproduced any more; the right to issue credit money, which is restricted to organizations with a banking licence; and the right to represent clients in court, which is restricted to members of a Bar association.16 Essentially, it is a claim on what Marx called the pool of social surplus value — which is enormous compared to any individual production capitalist, circulation capitalist, landowner, patent holder and so on.

By contrast, in neoclassical economics — in general equilibrium -incomes must by definition reflect productivity. There is no space for rents, in the sense of people getting something for nothing. Tellingly, Walras wrote that the entrepreneur neither adds nor subtracts from value produced. General equilibrium is static; neither rents nor innovation are allowed. A relatively recent refinement, the more flexible partial equilibrium analysis, allows us to disregard interactions with other sectors and introduce quasi-rents, and has since the 1970s led to the idea of ‘rentseeking’ by creating artificial monopolies, for example tariffs on trade.

The problem is that there is no hard-and-fast criterion with which to assess whether the entrepreneur creates ‘good’ new things or is imposing artificial barriers in order to seek rents.

The neoclassical approach to rent, which largely prevails today, lies at the heart of the rest of this book. If value derives from price, as neoclassical theory holds, income from rent must be productive. Today, the concept of unearned income has therefore disappeared. From being seen by Smith, Ricardo and their successors as semi-parasitic behaviour -extracting value from value-creating activity — it has in mainstream economic discourse become just a ‘barrier’ on the way to ‘perfect competition’. Banks which are judged ‘too big to fail’ and therefore enjoy implicit government subsidy — a form of monopoly — contribute to GDP, as do the high earnings of their executives.

Our understanding of rent and value profoundly affects how we measure GDP, how we view finance and the ‘financialization’ of the economy, how we treat innovation, how we see government’s role in the economy, and how we can steer the economy in a direction that is propelled by more investment and innovation, sustainable and inclusive. We begin by exploring in the next chapter what goes into — and what is omitted from -that totemic category, GDP, and the consequences of this selection for our assessment of value.

How the the accepted theory of value is used in computing GDP:

In this same way, the modern accounting concept of GDP is affected by the underlying theory of value that is used to calculate it. GDP is based on the ‘value added’ of a national economy’s industries. Value added is the monetary value of what those industries produce, minus the costs of material inputs or ‘intermediate consumption’: basically, revenue minus material input cost. Accountants call the intermediate inputs a ‘balancing’ item because they balance the production account: cost and value added equal the value of production. Value added, however, is a figure specifically calculated for national accounting: the residual difference (residual) between the resource side (output) and the use side (consumption).

The sum of all industry value-added residuals in the economy leads to ‘gross value added’, a figure equal to GDP, with some minor corrections for taxes. GDP can be calculated either through the production side, or through the income side, the latter by adding up the incomes paid in all the value-adding industries: all profits, rents, interest and royalties. As we will see below, there is a third way to calculate GDP: by adding up expenditure (demand) on final goods, whose price is equal to the sum of the value added along the entire production chain. So GDP can be looked at through production (all goods and services produced), income (all incomes generated), or demand (all goods and services consumed, including those in inventory).

So which industries add value? Following marginalist thinking, the national accounts today include in GDP all goods and services that fetch a price in the market. This is known as the ‘comprehensive boundary’. As we saw in Chapter 2, according to marginalism the only economic sectors outside the production boundary are government — which depends on taxes paid by the productive sectors — and most recipients of welfare, which is financed from taxation. Adopting this principle to calculate GDP might seem logical. But in fact it throws up some real oddities which call into question the rigour of the national accounting system and the way in which value is allocated across the economy. These oddities include how government services are valued; how investments in future capacity, such as R&D, are measured; how jobs earning high incomes, as in the financial sector, are treated; and how important services with no price (such as care) or no legal price (such as the black market) are dealt with. In order to explain how these oddities have arisen, and why the system seems to be so idiosyncratic, we need briefly to look at the way in which national accounting and the idea of ‘value added’ has developed over the centuries.

Arthur Cecil Pigou (1877–1959) argued GDP should measure welfare:

In the first half of the twentieth century marginalists had become aware of their theory’s limitations, and began to debate the inclusion of nonmarket activities in national income accounting. One of Alfred Marshall’s students, the British economist Arthur Cecil Pigou (1877–1959), who succeeded him as Professor of Political Economy at Cambridge, argued that since market prices merely indicated the satisfaction (utility) gained from exchange, national income should in fact go further: it should measure welfare. Welfare, Pigou argued, is a measure of the utility that people can gain through money — in other words, the material standard of living. In his influential 1920 book The Economics of Welfare, Pigou further defined ‘the range of our inquiry’ as being ‘restricted to that part of social welfare that can be brought directly or indirectly into relation with the measuring-rod of money’.8 On the one hand, Pigou was saying that all activities which do not really improve welfare (recall the discussion of welfare principles from Pareto discussed in Chapter 2), should be excluded from national income, even if they cost money. On the other hand, he stressed, activities which do generate welfare should be included — even if they are not paid for. In these, he included free or subsidized government services.

Simon Kuznets (1901–85) excluded government activity from GDP:

One of Pigou’s most prominent disciples was the first person to provide an estimate of the fall in national income of the United States during the Great Depression. The Belarusian-born Simon Kuznets (1901–85), a Professor of Economics at Harvard, won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1971 for his work on national accounts. Believing that they incurred costs without adding to final economic output, Kuznets, unlike Pigou, excluded from the production boundary all government activities that did not immediately result in a flow of goods or services to households — public administration, defence, justice, international relations, provision of infrastructure and so on.

John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946) accounted for govt spending in GDP:

In the late 1930s and the 1940s national accountants took up Keynes’s ideas about how government could invigorate an economy, and came to view government spending as directly increasing output. For the first time in the history of modern economic thought, government spending became important — in stark contrast to Kuznets’s omission of many government services from the national income. This redefinition of government as a contributor to national product was a decisive development in value theory. Keynes’s ideas quickly gained acceptance and were among the main influences behind the publication of the first handbook to calculate GDP, the United Nations’ System of National Accounts (SNA): a monumental work that in its fourth edition now runs to 662 pages.

This (I think) was the first time I had heard of the System of National Accounts, and I am now kind of interested to go find public data sets around this and take a look at them. A cursory search led to: https://www.bea.gov/data/economic-accounts/national

The SNA brings together various different ways of assessing the national income that had developed over centuries of economic thinking. Decisions about what gets included in the production boundary have been described as ‘ad hoc’, while national accountants admit that the SNA rules on production are ‘a mix of convention, judgment about data adequacy, and consensus about economic theory’. These include devising solutions based on ‘common sense’; making assumptions in the name of ‘computational convenience’ — which has important consequences for the actual numbers we come up with when assessing economic growth; and lobbying by particular economic interests.

In fairness, there have always been practical reasons for this ad hoc approach. Aspects of the economy, from R&D and housework to the environment and the black economy, proved difficult to assess using marginal utility. It was clear that a comprehensive national accounting system would have to include incomes from both market exchange and non-market exchange — in particular, government. With market-mediated activity lying at the heart of the marginalist concept of value, most estimators of national income wanted to adopt a broader approach.

Some more on how GDP is computed (in particular, this distinction between ‘intermediate’ and ‘final’ goods is an interesting one):

National income accounting, then, incorporates many different accounting methods. The system simultaneously allows an integrated view of the different aspects of the economy — both production (output) and distribution of income — and obliges national income accountants to link each commodity produced with someone’s income, thereby ensuring consistency. To maintain consistency between production, income and expenditure, the national accounts must record all value produced, income received, money paid for intermediate and finished goods and so on as transactions between actors in the economy — the government, or households or a particular sector — in which each actor has an account. This helps provide a detailed picture of the economy as a whole.

Expenditure on final goods must add up to GDP (as the price of intermediate goods goes into the price of the final goods). So it is possible to compute GDP from the expenditure side and, as we saw in Chapter 1, Petty used this method to estimate national output as early as the seventeenth century. Modern national accounts divide expenditure into the following categories:

GDP = Consumption by households © + Investment by companies and by residential investment in housing (I) + Government spending (G).

This can be expressed as: GDP = C + I + G.

For simplicity’s sake we will ignore the contribution of net exports. Two observations are in order: first, on the expenditure side, companies only appear as investors (demanding final investment goods from other companies). The remainder of spending (aggregate demand) is split between households and the government. Government expenditure is only what it spends itself; that is, excluding the transfers it makes to households (such as pensions or unemployment benefits). It is its collective consumption expenditure on behalf of the community. By focusing on government only in terms of the spending, it is by definition assumed to be ‘unproductive’ — outside the production boundary.

Much of government spending is classified as final (not intermediate) spending, so, Mazzucato argues, the value of government is undercounted in the GDP calculation:

Given these lower prices, the usual way of calculating value added for a business doesn’t work with government activities. Let’s recall that value added is normally the value of output minus costs of intermediate inputs used in production. The value added by a business is basically workers’ wages plus the business’s operating surplus, the latter broadly similar to gross operating profit in business accounting terms. So adding up the nonmarket prices of government activities is likely to show less value added, because they are set with a different, non-commercial objective: to provide a service to the public. If the non-market prices of the output are lower than the total costs of intermediate inputs, value added would even show up as negative — indeed, government activities would ‘subtract’ value. However, it makes no sense to say that teachers, nurses, policewomen, firefighters and so on destroy value in the economy. Clearly, a different measurement is needed. As the British economist Charles Bean, a former Deputy Governor for Economic Policy at the Bank of England, argues in his Independent Review of UK Economic Statistics (2016),20 the contribution to the economy by public-sector services has to be measured in terms of ‘delivering value’.21 But if this value is not profit, what is it?

National accountants have therefore long adopted the so-called ‘inputs = outputs’ approach. Once the output is defined, value added can be computed because the costs of intermediate inputs, such as the computers that employees use, are known. But since government’s output is basically intermediate inputs plus labour costs, its value added is simply equal to its employees’ salaries. One significant consequence of this is that the estimate of government value added — unlike that of businesses — assumes no ‘profit’ or operating surplus on top of wages. (In Figure 8 above, the dark-grey line shows the value added of government; it is equal — with slight adjustments — to the share of government employment income in GDP.) In a capitalist system in which earning a profit is deemed the outcome of being productive, this is important because it makes government, whose activities tend to be non-profit, seem unproductive.

But then what about the light-grey line, which represents government final consumption expenditure? We have already seen that pensions and unemployment benefits paid by government are part of household final consumption, not government spending. More broadly, it is not obvious why government should have any final consumption expenditure in the way that households do. After all, companies are not classed as being final consumers; their consumption is seen as intermediate, on the way to producing final goods for households. So why isn’t government spending likewise classed as intermediate expenditure? After all, there are, for example, billions of school students or medical patients who are consumers of government services.

Indeed, following this logic, government is also a producer of intermediate inputs for businesses. Surely education, roads, or the police, or courts of law can be seen as necessary inputs into the production of a variety of goods? But herein lies is a twist. If government spending were to increase, this would mean that government was producing more intermediate goods. Businesses would buy at least some of those goods (e.g. some public services cost money) with a fee; but because they were spending more on them (than if government was not producing anything, and therefore not buying supplies from businesses), their operating surplus and value added would inevitably fall. Government’s share of GDP would rise, but the absolute size of GDP would stay the same. This does, of course, run counter to Keynesian attempts to show how increases in government demand could lift GDP.

Many economists made exactly this argument in the 1930s and 1940s -in particular Simon Kuznets, who suggested that only government nonmarket and free goods provided to households should be allowed to increase GDP. Nevertheless, the convention that all government spending counts as final consumption arose during the Great Depression and the Second World War, when the US needed to justify its enormous government spending (the spike in the light-grey line in Figure 8 in the early 1940s). The spending was presented as adding to GDP, and the national accounts were modified accordingly.22

Later in the twentieth century there were repeated attempts to clear up the confusion over whether certain kinds of government spending counted as intermediate or final consumption. This was done by identifying which government activities provided non-market and free services for households (for example, schools), as opposed to intermediate services for businesses (for example, banking regulation). The distinction is not easy to make. Governments build roads. But how much of their value accrues to families going on holiday and how much to a trucking company moving essential spare parts from factory to user? Neither family nor trucking company can build the road. But the family on holiday adds to total final demand; the trucking company is an intermediate cost for businesses.

In 1982, national accountants estimated that some 3 to 4 per cent of Swedish, German and UK GDP was government expenditure that, previously categorized as final consumption expenditure, should be reclassified as (intermediate) inputs for businesses. This had the effect of lowering government’s overall value added by between 15 to 20 per cent.23 To take an example of such reclassification, in 2017 the UK telecommunications regulator, Ofcom, compelled British Telecom (a private firm) to turn its broadband network operation Openreach into a separate company following repeated complaints from customers and other broadband providers that progress in rolling out broadband around the

country had been too slow and that the service was inadequate. At least part of the cost of Ofcom could be seen as beneficial to the private telecommunications sector. Yet the convention that all government spending should count as final consumption has proved remarkably resistant to change. Now we can see why government final consumption expenditure is bigger than its value added in Figure 8. The government’s value added only includes salaries. However, the government also purchases a lot of goods and services from businesses, from coffee to cars, from pencils to plane tickets, to the office rentals for regulating bodies such as Ofcom. The producers of these goods and services, not the government, take credit for the value added. Since government is treated as a final consumer, the purchase of goods and services increases its spending. Clearly, government expenditure can be higher than what it charges (e.g. fees for services) because it raises taxes to cover the difference. But need the value of government be undermined because of the way prices are set? By not having a way to capture the production of value created by government -and by focusing more on its ‘spending’ role — the national accounts contribute to the myth that government is only facilitating the creation of value rather than being a lead player. As we will see in Chapter 8, this in turn affects how we view government, how it behaves and how it can get ‘captured’ easily by those who confidently see themselves as wealth creators.

Basically, one of Mazzucato’s key arguments in this book is that we under account for the value of government because of some arbitrary decisions we make about the production boundary and what constitutes final vs intermediate government spending.

While I’m not completely sold we are under-valuing government, I learned a ton of economics history from this book and highly recommend reading the whole thing:

Mariana Mazzucato’s ****The Value of Everything**.**

Some of my recent essays on economics you may enjoy:

• Principles for Radical Tax Reform and a Universal Dividend • Speech is Free, Distribution is Not // A Tax on the Purchase of Human Attention and Political Power • Kinky Labor Supply and the Attention Tax • History of the Capital AI & Market Failures in the Attention Economy • Napkin Modeling the US Govt “P&L” // Income Tax and Redistribution Scenarios