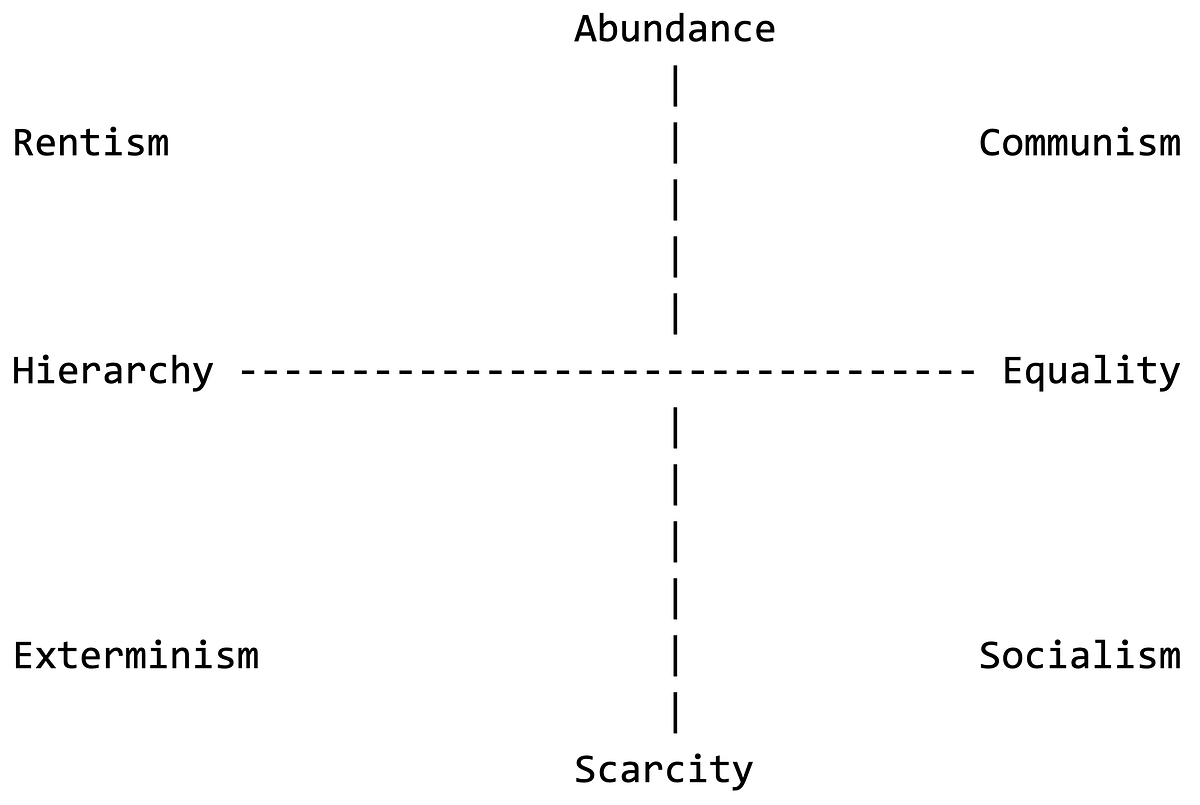

I just read Peter Frase’s Four Futures: Life After Capitalism twice — like The Lessons of History, it is both concise and full of great thinking, a rare occurrence. What is particularly refreshing about this discussion of what might come after capitalism is that it is neither utopian nor dystopian. Rather, the basic approach is to frame the possibilities as a 2x2 matrix, with an abundance/scarcity axis and a hierarchy/equality axis.

It mixes a bit of science fiction with history and political philosophy and is one of the more sober bits of futurism I have read.

Notes and quotes…

I really appreciate the admission that doing away with capitalism does not mean you eliminate status and power dynamics — you just swap out money for a different form of power (rather, a different set of power hierarchies, which he argues would be more diverse since everything under capitalism is fungible for money):

A communist society would surely have hierarchies of status — as do capitalist and all societies. But in capitalism, all status hierarchies tend to be aligned, albeit imperfectly, with the master hierarchy of capital and money. The ideal of a postscarcity society is that various kinds of esteem are independent, so that the esteem in which one is held as a musician is independent of the regard one achieves as a political activist, and one can’t use one kind of status to buy another. In a sense, then, it is a misnomer to refer to this as an “egalitarian” configuration; it is not, in fact, a world that lacks hierarchies but rather one of many hierarchies, no one of which is superior to any other.

This jab at Wikipedia made me chuckle:

In principle, Wikipedia bills itself as “the encyclopedia that anyone can edit,” a perfectly democratic and flat institution. In practice, it is neither so structureless nor so egalitarian. Partly this is because it reinscribes the inequalities of the society around it: a disproportionately large number of editors are white men, and the content of Wikipedia reflects this. With only 13 percent female contributors according to a 2010 survey, things like feminist literature get lesser coverage than minor characters from The Simpsons.

As did this jab at Star Wars, which I have always thought was kind of overrated and popular mostly because light sabers are cool toy merchandise:

Certain types of speculative fiction are more attuned than others to the particularities of social structure and political economy. In Star Wars, you don’t really care about the details of the galactic political economy. And when the author tries to flesh them out, as George Lucas did in his widely derided Star Wars prequel movies, it only gums up the story. In a world like Star Trek, on the other hand, these details actually matter. Even though Star Wars and Star Trek might superficially look like similar tales of space travel and swashbuckling, they are fundamentally different types of fiction. The former exists only for its characters and its mythic narrative, while the latter wants to root its characters in a richly and logically structured social world.

A postwork future of automation robots does not necessarily entail abundance:

Why, the reader might ask, is it even necessary to write another book about automation and the postwork future? The topic has become an entire subgenre in recent years; Brynjolfsson and McAfee are just one example. Others include Ford’s Rise of the Robots and articles from the Atlantic’s Derek Thompson, Slate’s Farhad Manjoo, and Mother Jones’s Kevin Drum. Each insists that technology is rapidly making work obsolete, but they flail vainly at an answer to the problem of making sure that technology leads to shared prosperity rather than increasing inequality. At best, like Brynjolfsson and McAfee, they fall back on familiar liberal bromides: entrepreneurship and education will allow us all to thrive even if all of our current work is automated away.

The one thing missing from all these accounts, the thing I want to inject into this debate, is politics, and specifically class struggle. As Mike Konczal of the Roosevelt Institute has pointed out, these projections of a postwork future tend toward a hazy technocratic utopianism, a “forward projection of the Keynesian-Fordism of the past,” in which “prosperity leads to redistribution leads to leisure and public goods.” Thus, while the transition may be difficult in places, we should ultimately be content with accelerating technological development and reassure ourselves that all will be for the best in the best of all possible worlds.

This outlook ignores the central defining features of the society we currently live in: capitalist class and property relations. Who benefits from automation, and who loses, is ultimately a consequence not of the robots themselves, but of who owns them. Hence it is impossible to understand the unfolding of the ecological crisis and developments in automation without understanding a third crisis through which both are mediated, the crisis of the capitalist economy. For neither climate change nor automation can be understood as problems (or solutions) in and of themselves. What is so dangerous, rather, is the way they manifest themselves in an economy dedicated to maximizing profits and growth, and in which money and power are held in the hands of a tiny elite.

A really interesting longer bit on intellectual capital, something I wish more of the data as labor/property advocates would consider the implications of:

The very definition of intellectual property demonstrates what a malleable concept “property” can be. While its defenders tend to speak of it as though it is broadly analogous to other kinds of property, it is actually based on a quite different principle. This irks even some conservative libertarian economists, like Michele Boldrin and David K. Levine. In their book Against Intellectual Monopoly and other works, they observe that intellectual property rights mean something quite different from property rights in land or physical objects.

The right to intellectual property is ultimately not a right to a concrete thing but to a pattern. That is, it does not just protect “your right to control your copy of your idea” in the way that it protects my right to control my shoes or my house. Rather, it grants the right to tell others how to use copies of an idea that they “own.” As Boldrin and Levine say,

This is not a right ordinarily or automatically granted to the owners of other types of property. If I produce a cup of coffee, I have the right to choose whether or not to sell it to you or drink it myself. But my property right is not an automatic right both to sell you the cup of coffee and to tell you how to drink it.

This form of property is by no means new. The writer’s copyright has been a part of English law since 1710, and the United States Constitution explicitly delineates the government’s right “to promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.” But the significance of intellectual property has increased, and it promises to continue increasing as the physical productivity of the economy grows.

In an echo of the struggle over enclosure, there are ongoing fights over the expansion of intellectual property into more and more areas. Fashion designers have historically not been able to copyright their designs in the United States, but large designers and their legislative allies are pushing bills that would allow them to sue the makers of cheap knockoff dresses and shoes. More ominous is the move to extend intellectual property protection to nature itself. In the 2013 decision Bowman v. Monsanto Co., the US Supreme Court upheld the conviction of Vernon Bowman, an Indiana farmer who had been found guilty of violating patents held by the agribusiness giant Monsanto. His crime was to plant seeds from a crop of soybeans that contained genetically modified “Roundup Ready” genes that made them resistant to herbicide. The decision affirmed Monsanto’s ability to force farmers to buy seeds anew every year, rather than use the seeds from the previous year’s crops.

If you were going to reduce from 4 to just 2 possibilities, this sounds about right:

Rosa Luxemburg, the great early twentieth-century socialist theorist and organizer, popularized a slogan: “Bourgeois society stands at the crossroads, either transition to socialism or regression into barbarism.” That’s truer today than it has ever been. In this book, I will suggest not two but four possible outcomes — two socialisms and two barbarisms, if you will.

I highly Rx reading Peter Frase’s Four Futures: Life After Capitalism in full.