The 2020 documentary The Social Dilemma raises a number of legitimate concerns about the negative impacts of social media technology on our society, but it somehow fails to connect the dots from its critique of social media to a far broader set of problems. The danger of this narrow view is that it leaves the audience thinking the problems are specific to social media, an idea which is likely to result in scapegoating social media platforms without addressing the more pervasive underlying issues. The ‘social dilemma’ is not specific to social media – the same incentives and methodologies driving all of the problems the film spotlights are also ultimately the same ones that contaminate all the other media and communication we encounter in our advertising driven, consumer capitalist version of democracy.

If you watch the film, I encourage you to think about how we must address these problems not only within the realm social media, but in society more broadly, across all media and technology we use to communicate with our fellow citizens.

How Social Media Technology Influences Social Behavior

To the film’s credit, it does a decent job of enumerating many of the ways that social media shapes social behavior:

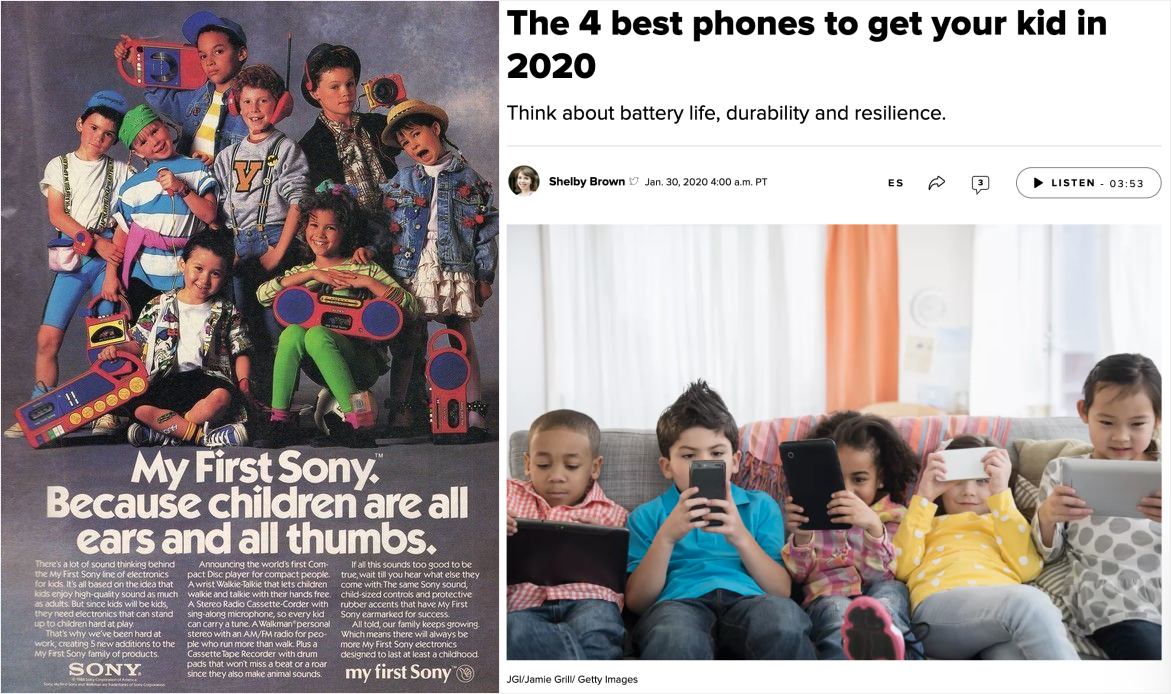

1. The hardware form factor of content delivery is new – mobile phones are ubiquitous and every member of the household has one. In past generations, a household consumed the same content (a single copy of a newspaper), often together, at the same time (sitting around a radio or TV together). Mass market paperbacks and cheap consumer electronics – VHS, cable TV proliferation, personal devices like the Walkman, etc – arguably were all steps towards “personalized” (and isolated) consumption. In the 90s, you already had kids watching MTV in the basement, mom watching the news, dad watching golf… So while fragmentation is not necessarily a totally new phenomenon, it is fair to say that never before has every individual’s world been so personalized, fragmented, and disconnected. This cannot be good for social cohesion.

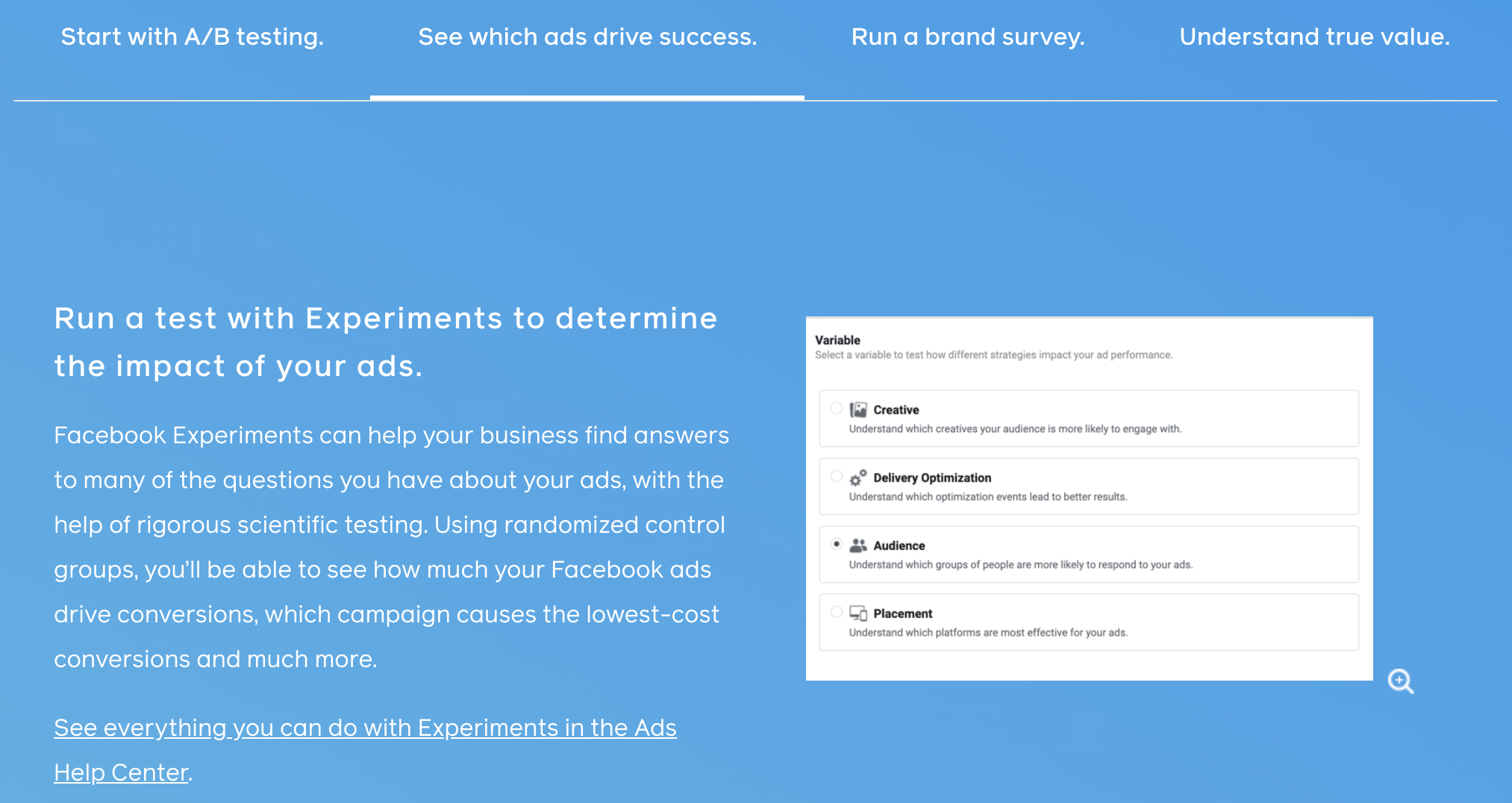

2. Consumer software is designed to be addictive and attention grabbing, with elements like red badges and infinite scroll feeds (not unlike magazine covers at the grocery checkout or the endless channel surfing offered by cable TV). While media and advertising have long made use of these tactics, the internet now enables rapid improvement of the best attention grabbing techniques via the standard practice of massive scale A/B experimentation.

3. Internet media companies can use algorithms to take advantage of ideas from psychology (like variable ratio reinforcement, the reward pattern of slot machines) to increase the addictiveness of their software. Notably, the movie fails to acknowledge that all content delivered over the internet – not just social media, but “news,” product merchandising, music, studio TV and film entertainment, Netflix (the distributor of The Social Dilemma), reference websites for technical q&a or medical information, personal blogs – pretty much all content delivery on the internet exploits these algorithms.

4. Social media leverages friend endorsements to earn your attention and trust – a point that gets less attention than it should in a movie that is nominally about the problems new and specific to social media. You are more likely to click / trust a link accompanied by a face you know. Print ads and TV commercials have long leveraged a similar tactic by paying celebrities with broad public recognition to endorse their products. Likewise, before the proliferation of social media, political ads sought the American “everyman” and national political campaigns selected “random” citizens to ask questions at publicized town halls:

Maybe they really can coexist – humanity and politics, shrewdness and decency. But it gets complicated. In the Spartanburg Q&A, after two China questions and one on taxing Internet commerce, as most of the lobby’s pencils are still at the glass making fun of the local heads, a totally demographically average 30-something middle-class soccer mom in rust-colored slacks and those round, overlarge glasses totally average 30-something soccer moms always wear gets picked and stands and somebody brings her the mike. It turns out her name is Donna Duren, of right here in Spartanburg SC, and she says she has a fourteen-year-old son named Chris, in whom Mr. and Mrs. Duren have been trying to inculcate family values and respect for authority and a noncynical idealism about America and its duly elected leaders.

– David Foster Wallace, John McCain, The Weasel, Twelve Monkeys, and the Shrub

This is an age-old tactic – well, at least one dating back to the dawn of mass media – of making appeals to the authority of tribe, of trying to persuade you by showing you “people just like you” rather than making an appeal to reason.

Alternatively, appeals to popular authority sometimes feature experts, who are explicitly not “just like you.” While expert knowledge is in many cases superior to the cursory beliefs we might have as non experts, how and why we give credence to experts matters, as Agnes Callard recently wrote in an op-ed arguing that philosophers should not sign petitions:

The petition aims to effect persuasion with respect to what appears in the first part not only by way of any argument contained therein but also by way of the number and respectability of the people who figure in the second part.

….

The problem is that even if it’s true, the fact that many believe it doesn’t shed any light on it why it’s true — and that is what the intellectually inquisitive person wants to know…. One expert is a learning opportunity; being confronted with an arsenal of experts is about as conducive to conversation as a firing squad.

Petitions make appeals to popularity (an “arsenal” of signers) or authority (the credentials of “expert” signers) – and Callard rightly points out that neither of these help the audience learn.

This I think is the crux of the real dilemma of social knowledge – while it is indeed a superpower that our species can leverage the aggregate knowledge of past generations and experts in any field, making use of an idea we do not fully understand always exposes us to some risk. Placing more credence in ideas that are more broadly accepted or endorsed by experts can reduce our exposure when we take such risks or act as a sort of shortcut to finding the best ideas we have not necessarily verified for ourselves, but this cannot serve as a complete substitute for understanding. Or, as Callard puts it, when we leverage social knowledge, it is easy to miss out on a “learning opportunity.”

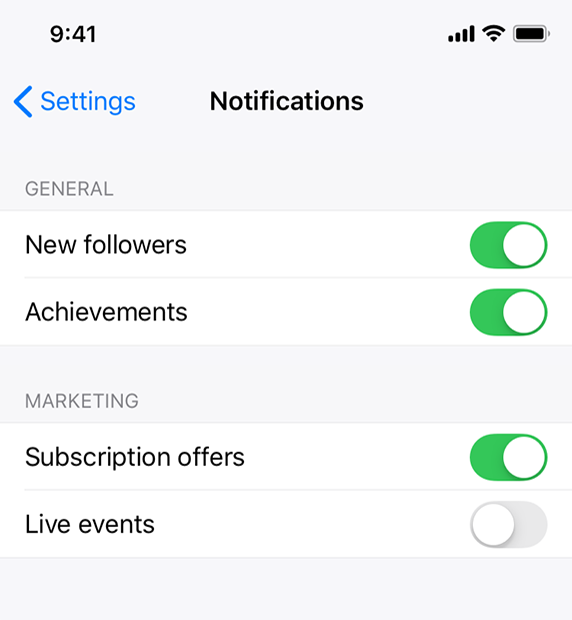

5. Mobile software leverages push notifications to grab your attention even when you have not explicitly chosen you want to look at your phone. This has made one of the most distasteful elements of consumer capitalism – advertising – more pervasive than ever. It is now available in the form of an API to every app installed on your phone.

Notifications - System Capabilities - iOS - Human Interface Guidelines - Apple Developer

Notifications - System Capabilities - iOS - Human Interface Guidelines - Apple Developer

Again, I don’t think pervasive advertising is fundamentally new – for a long time, we’ve had similarly intrusive advertising in public spaces with billboards or Cinnabon pumping their scents into the air or telemarketers and political campaign robo-dialers calling your home and cell phone or below minimum wage activists accosting you on the street or town council candidate posters staked in suburban front lawns or stickers of fish with feet on car bumpers or any t-shirts with words or logos on them. We can no longer call most of the spaces we occupy outside of our home or office “public” spaces – they are nearly all “commercial” spaces. Think about the design of the Whole Foods, of Bed Bath & Beyond, think of the language on the menu at your favorite restaurant (“locally farmed organic small batch hand massaged kale”) or the vibe of your local coffee shop – all of these are designed and optimized for conversion, just like the internet. We would do well to remember that the internet is far more a commercial space than it is a public space. (The greatest trick the Devil ever pulled was convincing the world he didn’t exist…)

6. The internet and social media have decentralized and democratized content production and distribution more than ever before. You might argue that this decentralization and democratization first became available with the advent of the printing press, which enabled people to print pamphlets, but it is fair to say that today content production and distribution are far lower cost and more broadly accessible than ever before.

7. Similarly, the reach and speed of the internet used to be only accessible to a very few centralized broadcasters in the era of TV / radio. Now these are far more broadly accessible than ever before.

The Problem is Not Social Media

While The Social Dilemma correctly identifies many of the systemic failures that have been introduced (or exacerbated) by social media technology, it does not draw historical parallels to similar challenges posed by other new communication technologies that changed the way we debate in public, understand our fellow citizens, and work towards consensus. The film fails to locate the “dilemma” as a fundamental challenge of social coordination and democracy that extends far beyond the domain of social media.

As a result, if you might walk away from the film thinking “all we have to do is fix social media.” In the best case, this might result in a local “solution” that simply pushes the same problems to another domain or medium.

This is not to say we can ignore the very real problems the film does highlight – we should certainly address these problems:

Addiction to mobile devices can result in isolation and depression.

Demagogues and profiteers can exploit powerful new technology to amplify their own voices for personal gain.

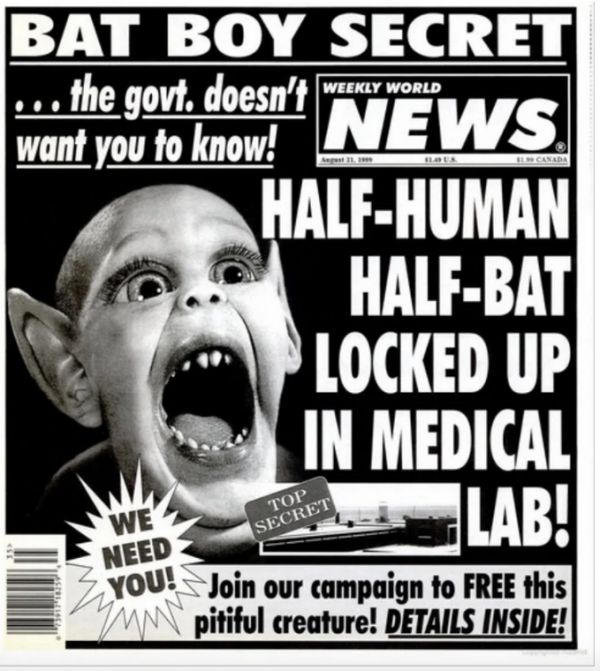

Misinformation and ‘fake news’ can degrade trust in institutions and fragment our worldviews with conflicting ideas about what constitutes reality, making it difficult to reach consensus on public policy.

Bat Child, Weekly World News.

Bat Child, Weekly World News.

But the film does not propose any great ideas for solving these problems …

Censorship is a Slippery Solution

Understandably, the natural response to all of these threats – addiction, misinformation, exploitation by demagogues – is to try to prevent them. The simplest reaction is prohibition, which might be appropriate in some domains (eg, with opiates).

But in the realm of communications technology, prohibition amounts to censorship. This might take the form of (1) calls for the corporate owners of social media platforms to perform more stringent content ‘moderation’ or (2) public mobs cancelling speakers who have uttered phrases they disagree with.

In either case, these strategies can seem attractive when you imagine they will only ever apply to the censorship of speech of others when you disagree with it, but they are far less attractive when you imagine others use them to silence your own speech.

And, the deeper problem with both of these flavors of censorship is that there is no codified set of rules agreed upon by the public defining exactly what speech should and should not be censored, which would leave this arbitration to the whim of corporations and mobs.

If indeed some sort of moderation and limits are necessary to counterbalance the powerful new distribution and amplification powers granted by new technology, it is crucial that the rules for these limits be decided by the public and encoded as laws or arbitration processes that are subject to public scrutiny, so that the rules are applied fairly.

Even if you suppose the public can design appropriate limits on speech amplified by technology – which, I grant, is very likely necessary in some form – it is a dangerous place to introduce legislation.

For, unlike the case of, say, opiates, speech technology is instrumental to citizens critiquing, resisting, and keeping in check the powers of a corrupt state – and if the public encodes limits on speech that are too stringent, it may limit its ability to critique or change these restrictions in the future. This is one reason zealots are so paranoid about protecting free speech.

There are no clean answers, and however you draw the lines, some sort of asymmetric power is likely to result. In one extreme, you can imagine granting the state monopoly power over speech and tools it can use to massively amplify its own message and censor any messages it disagrees with. In another case, you can imagine a sort of wild west where nothing is censored, and the loudest, most extreme (and potentially hateful, dangerous, or violent) messages are free to propagate. In yet another case, where dollars are fungible for eyeballs, the broadest reach goes to the incumbents with the biggest advertising spend.

Each of these systems would have a distinct set of failure modes – worth evaluating not only in the average or ‘somewhat failing’ case, but also in the worst case scenario.

Media Literacy and Counter-Intelligence Tech is Half Baked

Far preferable to censorship (imho) would be some sort of counterintelligence strategy or technology, some mechanism we might use to massively level up our sense-making abilities – either as individuals or as a public.

There are rudimentary ideas floating around in this vein – eg, broad education about identifying fake news or misinformation. You might even say that The Social Dilemma is an example of such an effort. There are also efforts to develop ‘AI’ for detecting fake news.

The issue with a lot of these proposals is that they are not aligned with the interests of any institution with the power to broadly execute on them. I think the only way sense-making technologies and techniques will emerge is in a bottoms up fashion – almost guerilla-style – when the broader public realizes it is in their own self-interest, for existing institutions certainly don’t see an educated public of voters or consumers as aligned with the maintenance of their power.

But figuring out exactly how to navigate this landscape is complicated. You might start by massively discounting the veracity of all information that seeks you out (vs information you actively looked for) – because if the information is seeking you, and you’re not profiting from it, then someone else is. But you also don’t want to completely stick your head in the sand, because that cuts you off from the messages of your guerilla compatriots. And don’t forget, many of the messages from your friends on the ground that appear to emerge bottoms up are actually curated by corporate interest! Yikes…

The Real Dilemma

He who fights with monsters should take care he does not become a monster himself. – Beyond Good and Evil

The real dilemma – both for the film and for our society – goes unaddressed explicitly in the film and runs throughout as an implicit undercurrent in how the film attempts to present its argument. When you try to address problems of information sharing and attention economics, you encounter a Catch-22, a tension between distribution and persuasiveness on the one hand vs intellectual honesty and sound argument (in the sense that Callard desires) on the other hand. And it is here that the film fails in the same way as a TED Talk.

The Social Dilemma aspires to educate its audience, yet it expects too little of them.

A key premise of the film is that social media has eroded our attention span, left us with an appetite only for short bursts of entertainment, and dulled our ability to appreciate diverse perspectives and arguments that challenge our view of the world.

How do you speak to such an audience? Like a TED Talk, the film tries to neatly package up the simplest possible, one-sided argument it can.

While I certainly appreciate old-school, print journalism principles like brevity, clarity, and information hierarchy (“don’t bury the lead”) – I have far less sympathy for the critique “this is too complicated” (with the implied elision: “for the general public to understand,” “to scale,” “to attract attention,” etc). I’m not saying that we should abandon Occam’s razor – we should certainly seek the simplest explanations for the phenomena we encounter.

But the reality is that life is pretty complex, democracy is messy, and understanding the diverse perspectives of our fellow members of society requires a lot of effort.

Expecting too little of your audience is a tempting short term strategy – and it arguably leads to some wins in the short term. But ultimately this strategy further infantilizes an audience already trained to expect every answer and service to be spoon fed to them without any personal effort, via “frictionless” economic transactions (ideally at “low low prices”).

You can see how almost anyone addressing a broad audience collapses the capable listener into the mindless consumer wherever you look. Elected representatives compete for your attention with the news media and entertainment media. They don’t expect us to have informed opinions or understand why a certain position is better than another – they just ask us to vote for a particular party – the election game is all about “voter turnout” – not the best outcomes.

Likewise, The Social Dilemma must compete with your attention with all of these and with the latest superhero movie. In its effort to win attention, the film not only ignores much of the complexity of the problems it seeks to address, but also makes stylistic choices that may ultimately work against it.

Wait, Wasn’t this Movie Supposed to be an Indictment of Corporate Style and Technique?

Visually, the film looks like a Facebook or Google commercial – an expensive, very “produced” visual aesthetic that to me makes the film feel a little too slick and corporate and a bit less authentic.

The film mixes the interviews with a staged ‘dramatic’ narrative about a fictional family of actors playing people struggling to deal with their kids being addicted to social media and some over-the-top VFX scenes where one of the actors from MadMen is supposed to personify an AI that is tuning an algorithm to ‘hook’ one of the teens back into addiction to a phone. I understand the difficulty of explaining machine learning algorithms and their potential risks to the general public – tbh, a lot of the inner workings are black box even to software engineers working at companies deploying these algorithms. But I don’t think the personification ultimately explains much about how the algorithms actually work with any sort of useful accuracy – a more useful angle, imo, would be to explain the systems problems of attention economics / what happens when your time as a user is sold to the highest bidder, how this may or may not be aligned with your best interests, why the problem extends far beyond the algorithms to all of the actors involved in the market for attention, etc. A few of the snippets of interviews with Jaron Lanier touch upon this and do far more to explain the problem than the VFX / AI scenes. (Btw, I highly Rx Lanier’s books Who Owns the Future? and You Are Not a Gadget as follow-ups if you like the film and want to go deeper).

Ultimately, the dramatic interludes fail because I just don’t think they do enough to make us care about the characters involved. It doesn’t feel like something real is at stake, it just feels like a half-hearted attempt to manufacture a vague instance of a real and broad social problem using a nameless family. Again, I am reminded of corporate consumer tech commercials – upbeat ukelele music, guy is totally disorganized and overwhelmed deadbeat, goes to fancy Blue-Bottle-type coffee shop, gets amazing new todo-list app, gets his life in order, meets girl of dreams, falls in love, marries, lives happily ever after sharing photos of cute children with the grandparents. Yes, this is sort of narrative and has a ‘character,’ but it’s too vague to evoke more feeling than a photo of a forlorn child in an ad for a non-profit.

And all of these stylistic elements just feel really expensive – like the film is throwing money at the problem of making its argument.

Maybe all of this high-budget aesthetic is what it takes to reach a mass audience and the style isn’t off-putting to anyone other than me, but the high-budget production value just feels totally dissonant with the message of this film, especially when I compare it to documentaries I love like The Act of Killing, Far from Vietnam, Influence, The Century of the Self, The Fog of War.

And, if you really can’t stomach low-budget docs, consider Spike Jonze’s film Her, which had a $23mm budget, is absolutely gorgeous, and treats the topic of loneliness and technology with all of the nuance it deserves in a beautiful film with deeply compelling characters.

Despite All That, You Should Probably Still Watch The Movie

All of that said, what I think works the best about The Social Dilemma is the set of interviews with the creators of these technologies who all say, “we’d never let our kids near this stuff.” You’ve got to imagine this is not too different from how the people who make Krispy Kreme donuts, American Spirit cigarettes, or Oxycontin feel about exposing their kids to the products they are selling to other people.

And, I do think The Social Dilemma does a nice job summarizing many of the key problems that modern communication technology presents for a democracy. It is worth watching, if nothing else, as a warm up for the 4-part, far more expansive documentary mini-series, The Century of the Self. This fantastic doc expands its critique far beyond specific technology to the values and techniques of the ruling class that emerged with the advent of mass media and have prevailed ever since.

On that half-recommendation, I’ll end and leave you with one historical exhibit illustrating the origins of ‘the dilemma’ that far predates social media. It’s from Edward Bernays’ 1928 book, Propaganda, the playbook for governance in the age of mass media:

The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country.

We are governed, our minds molded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of. This is a logical result of the way in which our democratic society is organized. Vast numbers of human beings must cooperate in this manner if they are to live together as a smoothly functioning society.

Our invisible governors are, in many cases, unaware of the identity of their fellow members in the inner cabinet.

[I]n almost every act of our daily lives, whether in the sphere of politics or business, in our social conduct or our ethical thinking, we are dominated by the relatively small number of persons-—a trifling fraction of our hundred and twenty million—who understand the mental processes and social patterns of the masses. It is they who pull the wires which control the public mind, who harness old social forces and contrive new ways to bind and guide the world.