The Beach Bum, 2019

The Beach Bum, 2019

My senior year of college, I was supposed to go to Key West for spring break with some friends.

The night before we were supposed to leave, I lost all my money in a poker game – like 800 bucks. A friend loaned me enough cash to pay for a bus to get down there, but not back.

When I got there, I found a job on a lobster boat – setting traps – and I made enough money to pay for beer.

Instead of staying one week, I stayed six.

I got back to campus for the end of the semester, walked into the dorm at six AM, and my roommate said, “Where have you been? Don’t you have finals?”

I have one at nine, I said.

It was a music final, in this big auditorium. I went in wearing faded blue jean cut off shorts, no shoes, not even flip flops, no shirt, long sun-bleached hair, and a long mustache. When the professor saw me he said, “Mr. Kortina, where have you been all semester?”

Didn’t you get my doctor’s note? I’ve been in the hospital with mononucleosis.

He just looked at me for a few seconds, then said, “If you have the balls to walk in here looking like that, with that story, I’m not going to ask you any more questions.”

This was my favorite story my dad used to tell me at bedtime when I was growing up.

What makes it such a good story? Or, at least, a story that I really like?

There’s the humor, of course. There’s also an irreverence to it, a sort of healthy disdain for institutions and bureaucracy, I suppose.

And, I guess it works out ok in the end, because what’s at stake is ultimately not much – just a music exam.

The Three Billy Goats Gruff

The Three Billy Goats Gruff

A few years ago, my dad told me, like he was realizing it for the first time, “You know, I don’t think I’ve ever finished reading a book in my life. Isn’t that kind of crazy? I got through all of high school, graduated from college, got a lot of decent jobs…”

As I’m reminiscing, I have to admit this is indeed kind of remarkable. But then I realize it’s not true. Another bedtime story my dad used to tell me was The Three Billy Goats Gruff, and I know he read that whole book to me many times.

I really like the idea that this is the only book he ever read. I like this idea even more than I like the lobster boat story.

Physio Control Defibrillator

Physio Control Defibrillator

When I was growing up in New Jersey, my dad had a bunch of sales jobs for medical equipment companies. He was on the road a lot. When he was good, he brought home plaques for things like Top Regional Sales Rep – but he never held one of these jobs for very long, a few years at most.

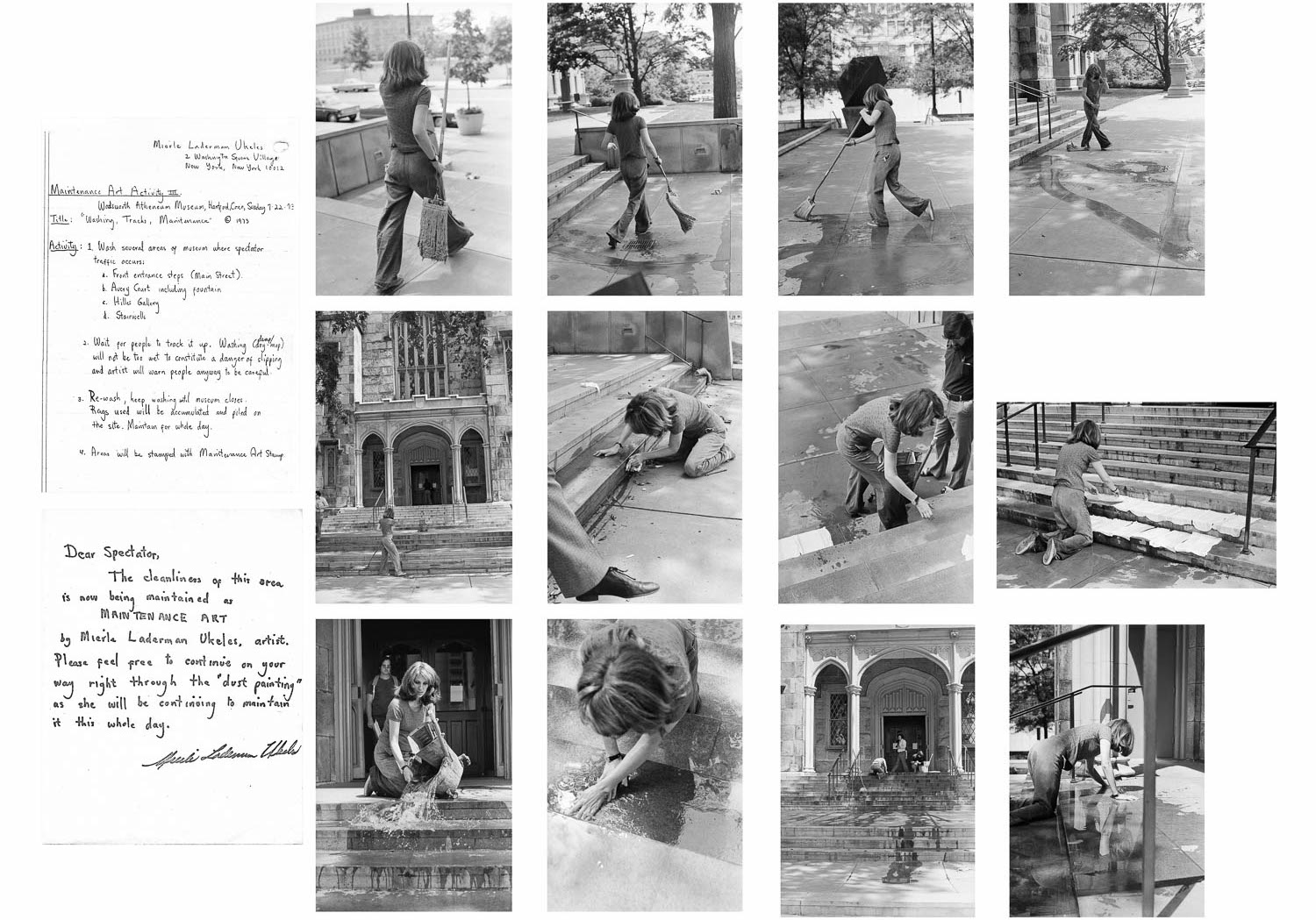

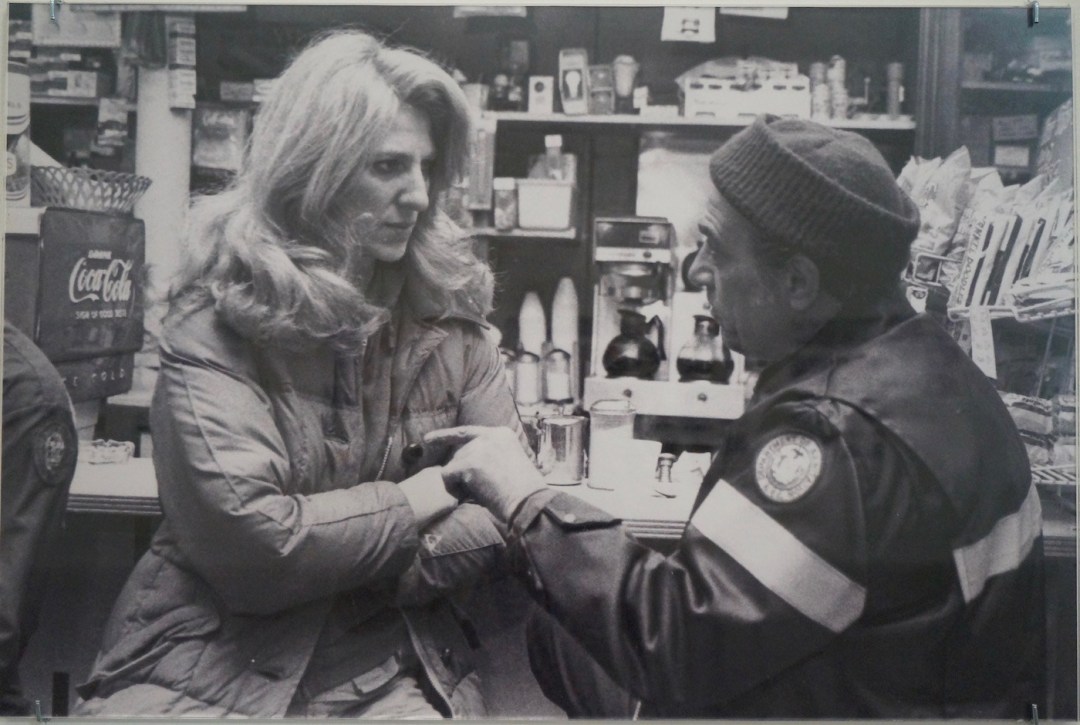

Mierle Laderman Ukeles via feldmangallery.com

Mierle Laderman Ukeles via feldmangallery.com

My mom worked two jobs. She had a nine to five job doing office admin work at Merck, and a few nights a week and during the day on weekends she worked a cash register at Sterns, a clothing store at the Bridgewater mall.

On her nights “off,” she would cook stuff like meatballs or beef stew, and we could heat the meals up on the nights that she worked at Sterns.

On weekends, she would leave us lists of chores written on little scraps of paper, each assigned to me or my sister – vacuum the living room, sweep the kitchen floor, mow the lawn, wash the windows in the bedrooms, clean the garage, etc.

We probably didn’t even do half of the chores, though – my mom did all the cooking, the grocery shopping, the laundry. She cleaned the bathrooms.

In her Manifesto for Maintenance Art, Mierle Laderman Ukeles juxtaposes:

B.

Two basic systems: Development and Maintenance. The sourball

of every revolution: after the revolution, who’s going

to pick up the garbage on Monday morning?

Development: pure individual creation; the new; change;

progress; advance; excitement; flight or fleeing.

Maintenance: keep the dust off the pure individual

creation; preserve the new; sustain the change;

protect progress; defend and prolong the advance;

renew the excitement; repeat the flight;

show your work—show it again

keep the contemporaryartmuseum groovy

keep the home fires burning

Development systems are partial feedback systems with major

room for change.

Maintenance systems are direct feedback systems with little

room for alteration.

C.

Maintenance is a drag; it takes all the fucking time (lit.)

The mind boggles and chafes at the boredom.

The culture confers lousy status on maintenance jobs =

minimum wages, housewives = no pay.

clean you desk, wash the dishes, clean the floor,

wash your clothes, wash your toes, change the baby’s

diaper, finish the report, correct the typos, mend the

fence, keep the customer happy, throw out the stinking

garbage, watch out don’t put things in your nose, what

shall I wear, I have no sox, pay your bills, don’t

litter, save string, wash your hair, change the sheets,

go to the store, I’m out of perfume, say it again—

he doesn’t understand, seal it again—it leaks, go to

work, this art is dusty, clear the table, call him again,

flush the toilet, stay young.

Mierle Laderman Ukeles via feldmangallery.com

Mierle Laderman Ukeles via feldmangallery.com

Everyone has heard the story about how the profit motive was supposed to lead to progress: because there is apparently no intrinsic motivation to take the risk of creating something new, we had to come up with a way to reward people for the various risks and costs inherent in the process of innovation.

Against this backdrop, the starving artist sort of seems like a miracle, an anomaly – a crazy person willing to take risk without any promise of profit.

I guess this is why I always thought of art, the avant-garde, and counter culture as acts of defiance – they serve as counterexamples to the story that justifies profit. They help us imagine a possible world without it.

But what Ukeles made me realize is that the profit motive and the art world both tend to favor the new, the creative act, development. Her art is radical and profound, because it instead celebrates maintenance.

Make no mistake: Ukeles is not opposed to progress and development of the new. The point is that development and maintenance are both essential, but these complementary systems are out of balance, because our culture biases toward mechanisms for recognizing and rewarding only one side of the equation. Here’s Ukeles again:

This is 1968, there was no valuing of ‘maintenance’ in Western Culture. The trajectory was: make something new, always move forward. Capitalism is like that. The people who were taking care and keeping the wheels of society turning were mute, and I didn’t like it! – (ARTnews)

JCPenny via bloomberg.com

JCPenny via bloomberg.com

When I was in high school, my mom moved down near Atlanta so that she and my sister and I could live with her parents. She thought maybe we could spend the money she saved on rent paying for college.

She got two jobs again, one working in an accounting department at the trucking company Ryder, one working on weekends at JCPenney.

My mom went to grad school (for psychology), so these jobs didn’t really put to use her education. One time I asked her if she regretted this. She said, “All I ever wanted was for you kids to be happy.”

The Wolf of Wall Street, 2013

The Wolf of Wall Street, 2013

My dad also eventually moved down to Atlanta – to live closer to me and my sister – and he came up with a clever scheme for making cash. He found this car repair place, and asked them how they advertise – in newspapers or whatever, when newspapers were more of a thing.

He proposed to them that he would print “vouchers” for 3 free oil changes and sell them to people for $30 in cash.

The oil change would cost the shop like $10, and serve as a loss leader. Once the car was in the shop, they would upsell the customer on a tune up, a tire rotation, or some other sort of fluid change, and recoup the marketing expense of bringing someone in for the free oil change.

So my dad would go to a restaurant, talk to everyone, explain he was saving them like $15 or $20 on every oil change (they were essentially getting a $30 value at $10 a pop), and if he got 5 people to buy one, he’d pocket $150 in cash, which he could do in like an hour.

What is really interesting about this is that although my dad had the shop’s permission, he was just designing and printing the vouchers at home – on an Epson inkjet printer – and then selling the printed pages for cash. The shop never touched any of that money, had no idea how many vouchers were printed – it was all totally abstracted.

The Alchemist via metmuseum.org

The Alchemist via metmuseum.org

According to wikipedia:

In alchemy, the term chrysopoeia (from Greek χρυσοποιία, khrusopoiia, “gold-making”) refers to the artificial production of gold, most commonly by the alleged transmutation of base metals such as lead…. [T]he making of gold and silver remained one of the defining ambitions of alchemy throughout its history, from Zosimus of Panopolis (c. 300) to Robert Boyle (1627–1691).

Goodfellas, 1990

Goodfellas, 1990

One of my dad’s favorite movies – and one of my favorite movies – is Goodfellas.

The first part of the movie is similar in tone to that lobster boat story.

But the stakes escalate. It’s a different story arc. It’s a rise and fall, a tragedy.

Maybe the lobster boat and oil change vouchers were just early episodes.

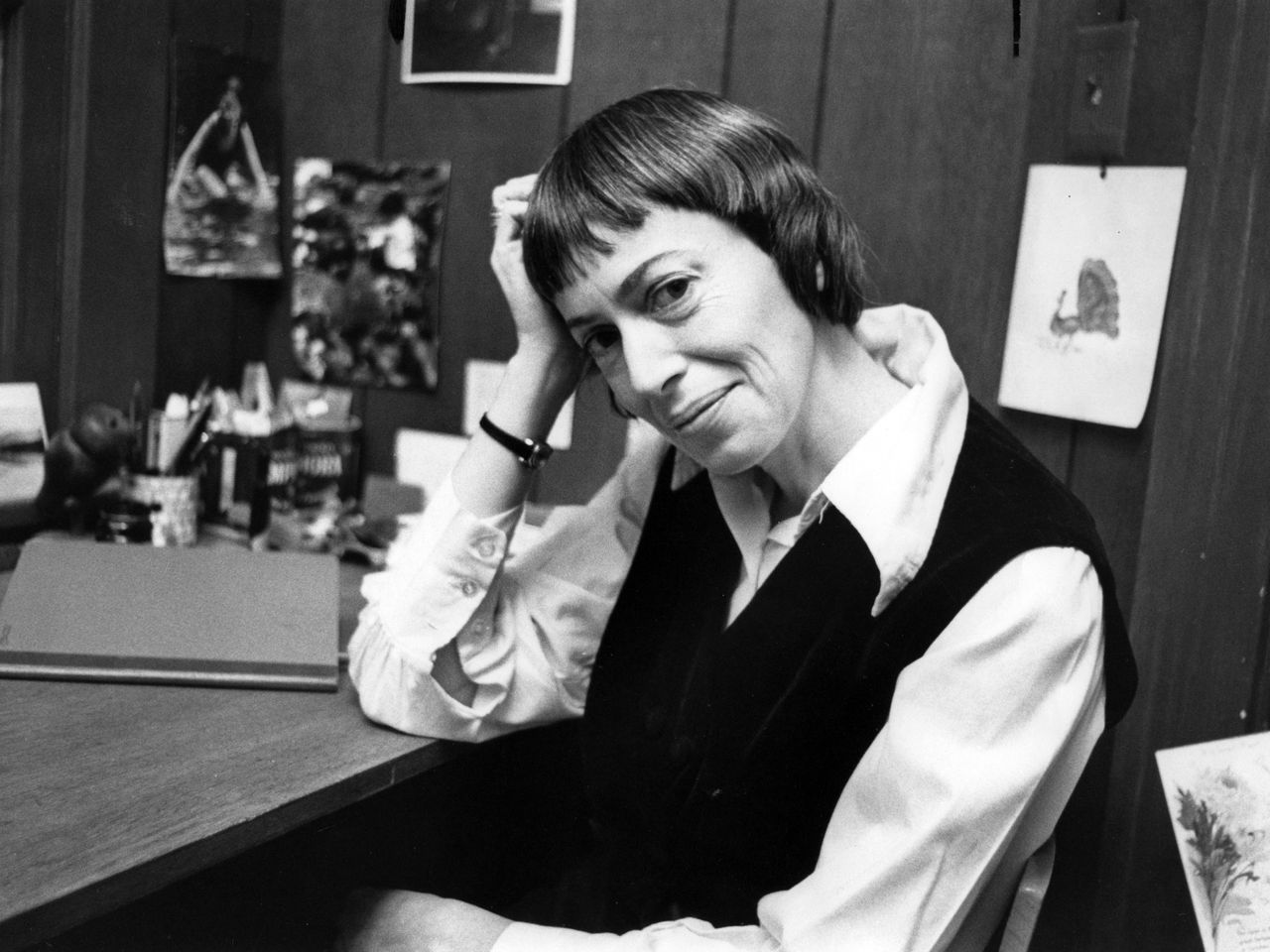

Ursula K. Le Guin via broadway.org.uk

Ursula K. Le Guin via broadway.org.uk

In the temperate and tropical regions where it appears that hominids evolved into human beings, the principal food of the species was vegetable. Sixty-five to eighty percent of what human beings ate in those regions in Paleolithic, Neolithic, and prehistoric times was gathered; only in the extreme Arctic was meat the staple food. The mammoth hunters spectacularly occupy the cave wall and the mind, but what we actually did to stay alive and fat was gather seeds, roots, sprouts, shoots, leaves, nuts, berries, fruits, and grains, adding bugs and mollusks and netting or snaring birds, fish, rats, rabbits, and other tuskless small fry to up the protein.

So begins Ursula le Guin’s essay, The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction. She goes on:

It is hard to tell a really gripping tale of how I wrestled a wild-oat seed from its husk, and then another, and then another, and then another, and then another, and then I scratched my gnat bites, and Ool said something funny, and we went to the creek and got a drink and watched newts for a while, and then I found another patch of oats…. No, it does not compare, it cannot compete with how I thrust my spear deep into the titanic hairy flank while Oob, impaled on one huge sweeping tusk, writhed screaming, and blood sprouted everywhere in crimson torrents, and Boob was crushed to jelly when the mammoth fell on him as I shot my unerring arrow straight through eye to brain.

That story not only has Action [with a capital-A], it has a Hero [with a capital-H]. Heroes are powerful. Before you know it, the men and women in the wild-oat patch and their kids and the skills of makers and the thoughts of the thoughtful and the songs of the singers are all part of it, have all been pressed into service in the tale of the Hero. But it isn’t their story. It’s his.

Fitzcarraldo, 1982

Fitzcarraldo, 1982

I love stories. Many of my favorites are feature films, and I especially love films that changed the way I think about the world.

It’s almost like magic, the way a story can change your mind about something, get you to see someone in a new way, get you to have more compassion.

I like the idea of a world with more compassion – it seems important right now – so I’ve been studying how storytelling works, how cinema works.

Hero With a Thousand Faces, 1949

Hero With a Thousand Faces, 1949

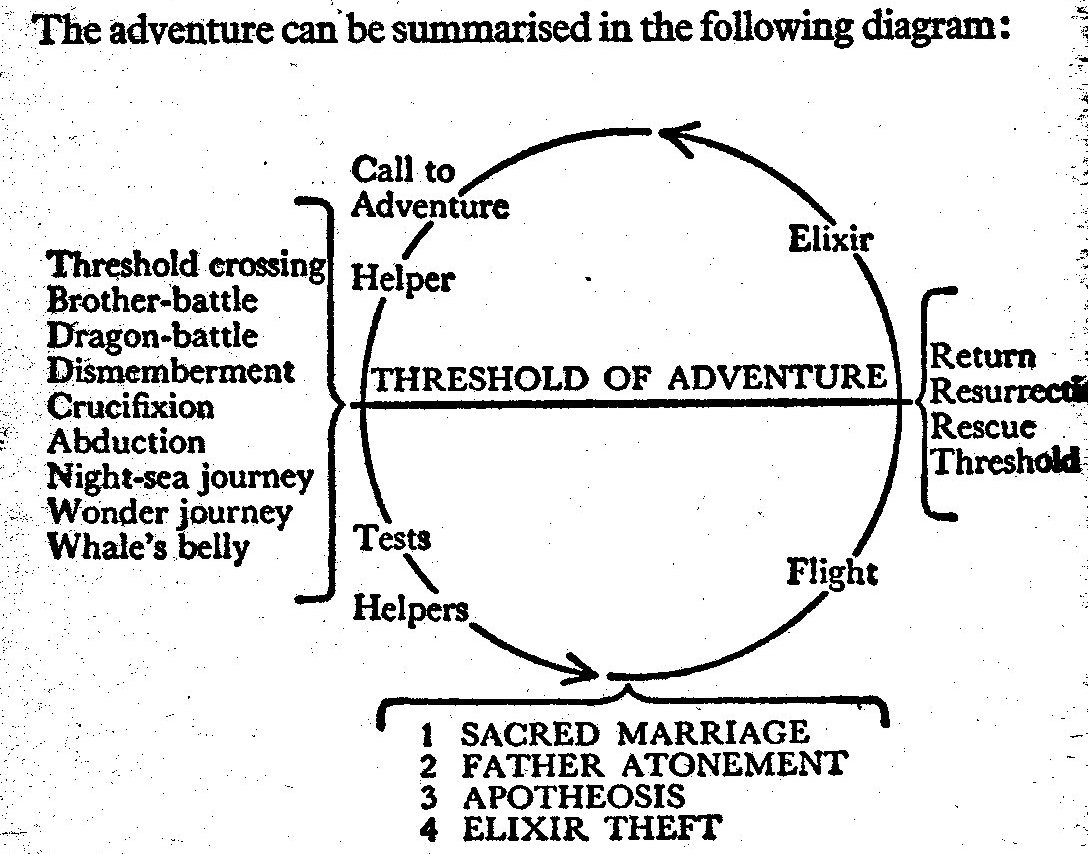

Memos have been written, books have been written, classes and entire film education tracks have been designed around Joseph Campbell’s “monomyth,” The Hero with a Thousand Faces, this idea that the universal narratives share the fundamental structure of a Hero’s journey.

In an infamous memo to the writers and story analysts at Disney, Christopher Vogler said that the ideas in Campbell’s book can help you “compose a story to meet any situation, a story that will be dramatic, entertaining, and psychologically true…. The ideas in it are older than the Pyramids, older than Stonehenge, older than the earliest cave painting.”

(Vogler sent this memo in 1986. Le Guin wrote The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction in 1988. Maybe Le Guin was responding to his memo, or maybe cave paintings were just a hot topic among writers’ writers in this decade.)

Vogler argues that Campbell’s monomyth supplies “a major tool for dealing more effectively with a mass audience.” And, the formula seems to work. Basically all the Disney and Pixar movies – and many (most according to many) Hollywood box office successes – follow the hero’s journey formula.

I suppose all the capital-A Action of the hero’s journey – threshold-crossings, brother-battles, dragon-battles, dismemberments, crucifixions, abductions, night-sea journeys, wonder journeys, whale’s bellies – all this keeps the audience “engaged.”

Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels, 1975

Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels, 1975

Yet the film that most demanded my active “engagement” has almost no capital-A Action.

The film is Jeanne Dielman, 23, Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, and watching it for the first time was probably the most profound film experience I’ve ever had.

It’s 3h 21m long. There is almost no dialog. It is mostly composed of long shots of the main character working in the kitchen.

3h 21m is just about how long it would take you to run a marathon at a 7m 30s per mile pace, and watching the film is about as strenuous as running a marathon.

You may try to watch it, if this is the first time you are hearing about it. And, there is a good chance you’ll get distracted, pull out your phone, or maybe even turn it off early – because it doesn’t use capital-A Action to activate your dopamine receptors. But this will be sad, because this film deserves your full attention, and it is well worth watching in its entirety.

Most of Jeanne Dielman’s hours are filled with domestic work, performed alone, in silence. But since this work doesn’t merit compensation under our economic regime, she earns money by turning tricks.

Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels, 1975

Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels, 1975

You will have what feels like as much time as Jeanne Dielman does to mull over this as you watch her cook dinner, alone, in silence – but you won’t really have as much time to think about this as she does, because you are only watching 3h 21m of her life.

We are inundated with stories by our culture, and our culture is optimized for growth, for profits, for sales. Capital-H heroes sell, capital-A Action sells, dopamine sells.

So it is rare to hear a story like Jeanne Dielman’s.

Dr. Strangelove Or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, 1964

Dr. Strangelove Or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, 1964

You were probably hoping to hear a story about a capital-H Hero today, even. Because you want to save the world – and you should want to save the world, because it needs saving.

But it is worth thinking about whether the way to save the world is by being a capital-H Hero.

Some people are trying this. Space exploration, for example.

Maybe some people will escape our planet before we destroy it, and maybe that is the best we can hope for at this point. But if we are honest about it, this seems like a consolation prize, not a way to save the world.

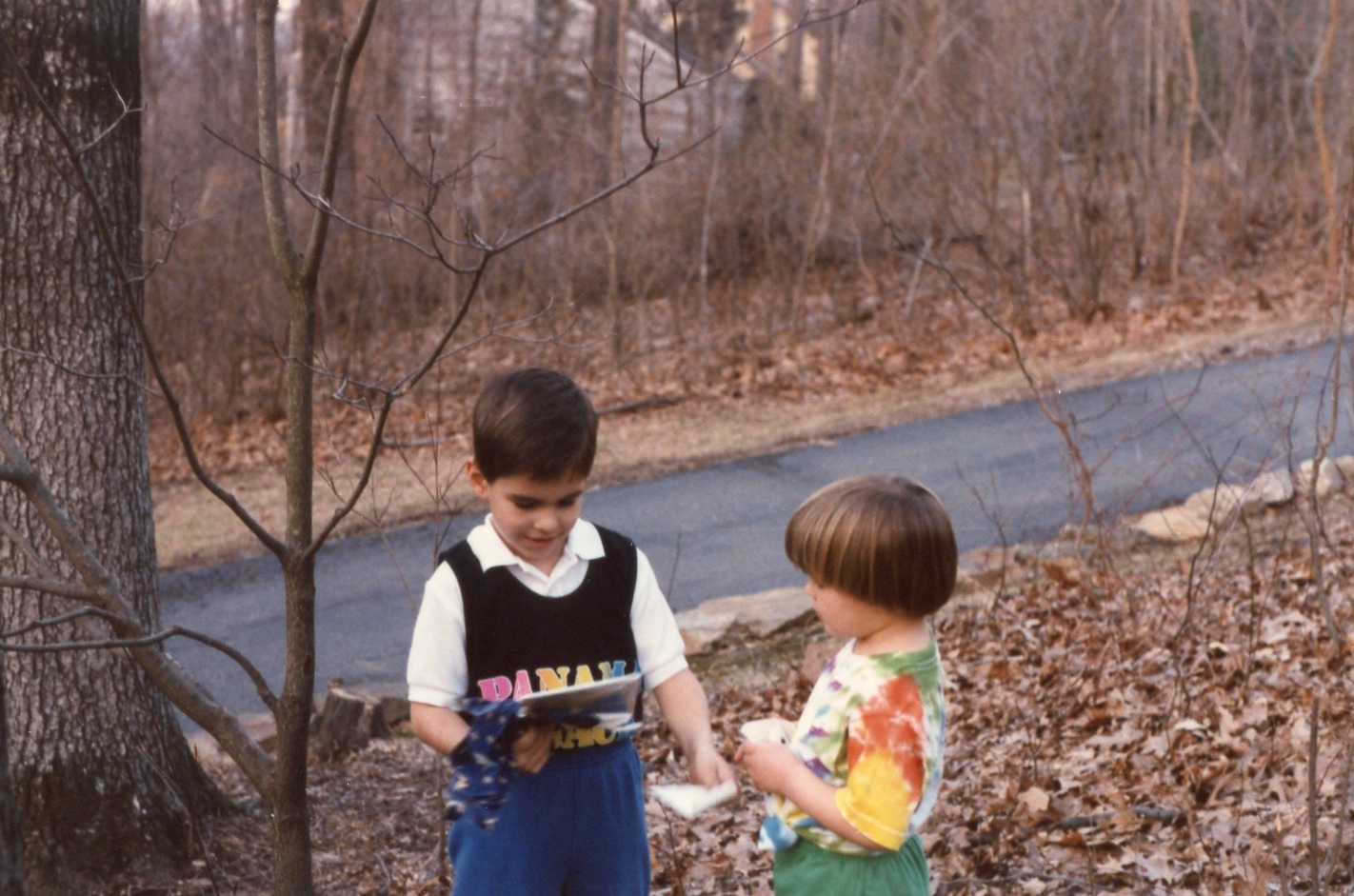

me and my sis via mom

me and my sis via mom

Back when my sister and I were little, on our birthdays, my mom would engineer these treasure hunts. She wrote clues on little scraps of paper – just like our lists of chores were doled out on.

The first clue of the day might be in the medicine cabinet next to the toothbrush – “do we need another cord?”

This would take you to the pile of firewood under the deck, where there would be a present hidden under a blue tarp and another scrap of paper with a clue on it.

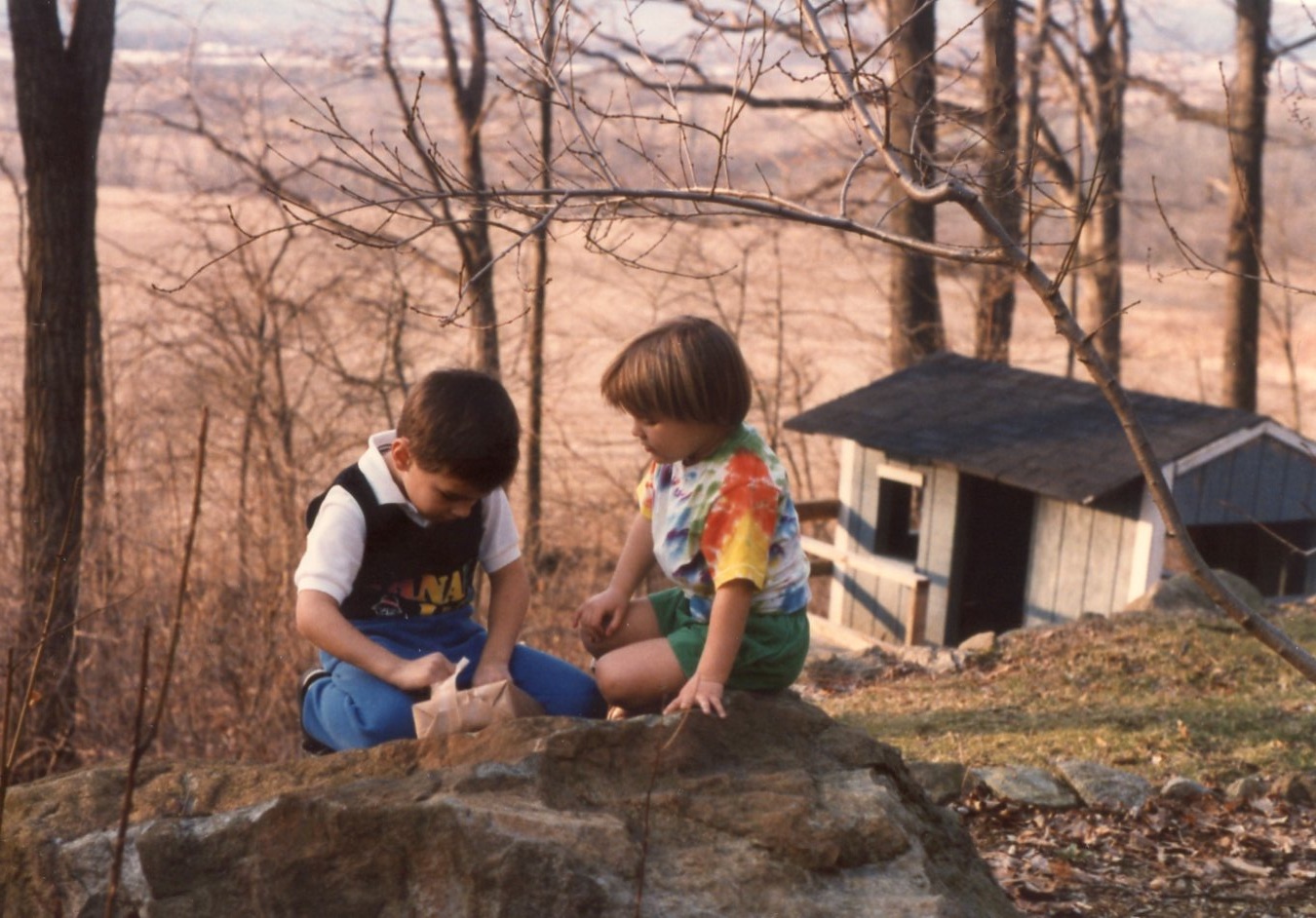

me and my sis via mom

me and my sis via mom

The presents were usually wrapped with brown paper Laneco grocery bags.

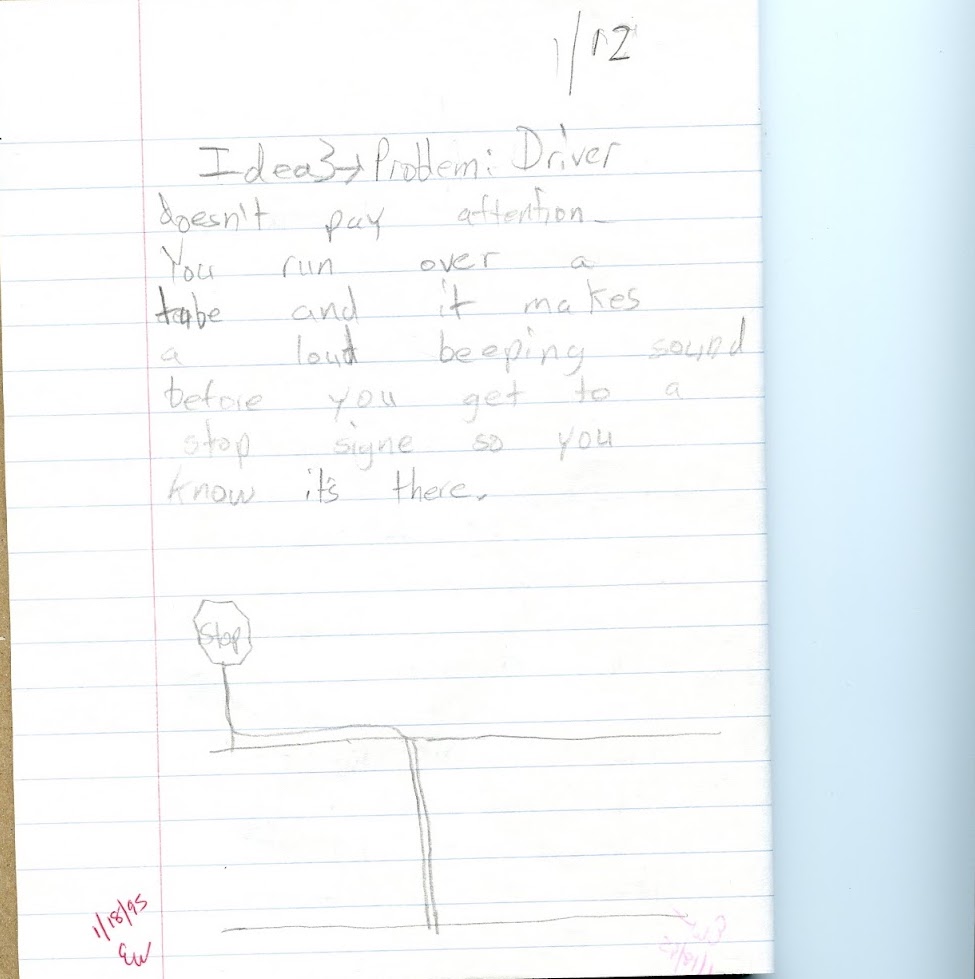

notebook scan via mom

notebook scan via mom

A few years ago, my mom scanned a bunch of artifacts from our childhood.

Many photographs of me and my sister that my mom had shot with a Pentax 35mm camera.

Works of art. Maps of fantasy lands drawn in colored pencil. Science class log books with inventions like this stop sign that beeps at you in case you missed the visual cue.

Journals. Absurd and satirical stories authored by my friend Dennis and me.

Handwriting-class homework assignments, coloring book pages, report cards, yellowed newspaper clippings.

Haikus. Watercolors.

My mom archived and filed these away in bankers boxes. She had the foresight to imagine we might look back fondly on these records of our childhood.

I don’t remember her ever asking me how to use a scanner. She must have bought one and figured out how to use it herself. And then one year on Christmas, she gave each of us a burned CD with a bunch of jpegs on it.

None of the treasure hunt clues survived, however. There was no one to preserve the things my mom made, no one to scan them years later and burn them onto a CD to give to her on Christmas.

A talk prepared for The Berkeley Forum speaker series in Sep 2021.