A talk prepared for UC Berkeley’s Build the Future speaker series in Oct 2018.

Thank you all for coming this evening. I want to preface this talk by warning you that it’s quite possible you’ll interpret much of this talk as cynicism. It is not my intention to be cynical. My goal is to treat you with respect by speaking to you honestly, without any grand illusions.

I don’t do a ton of these types of events, because I am afraid of producing something like a TED talk – a narrow, one sided picture of a thing, without any consideration for nuance or complexity. Despite your best efforts, these sorts of talks can often go that way…

I also don’t want to do anything that could be construed as “giving advice.” I once heard somewhere you should ask for stories not for advice. This seems like good advice… and probably applies to responding as much as it does to asking.

When people occasionally ask me who my mentors are, I get a puzzled look on my face. I picture some sort of formal engagement, like the one Beatrix has under “The Cruel Tutelage of Pai Mei” in Kill Bill Vol. 2. Pai Mei is the type of mentor I would want to have (and the type of mentor I would want to be).

But, since I do not have the privilege of having a formal mentor like Pai Mei, I try to learn from everyone I encounter.

The last person to ask me about my mentors was either a college student or a venture capitalist. I remember telling the venture capitalist that my mentors were: Iqram (my co-founder at Venmo), Stevie Wonder, Feynman, Aristotle….

Many of my favorite conversations have been with “mentors” who have been dead for over a hundred years. I often think about this when I’m at a dinner party.

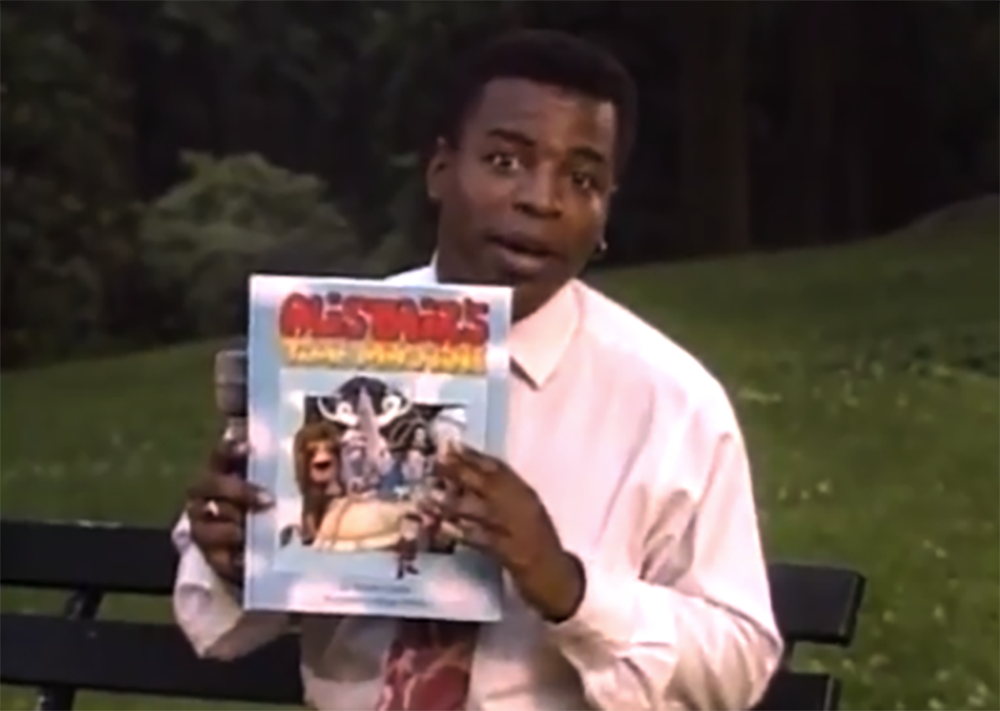

Before I continue rambling, another caveat, one that I learned as a kid watching Reading Rainbow. At the end of every episode, Levar Burton would give his opinion on a book, then remind you: “But you don’t have take my word for it.”

Levar was encouraging you to read the primary sources and confirm things with your own observation and judgment.

As a kid, a lot of my best memories are of building things. When my sister and I got into mountain biking, we spent more time building miles of trails in the woods near our house than we did riding our bikes on these trails. We’d cut down trees, clear underbrush, dig up roots (this was one of the hardest things), build jumps and obstacles.

I remember we built this one bridge over a stream with a 12 in x 12 in x 10 ft piece of lumber that we scavenged from someone’s leftover deck build materials, a log of the same diameter, and the slats from a wooden pallet we took apart.

This is my friend Dennis – rather, a drawing based on a photo of him, which I used in a story I wrote a few years ago. Looking back at childhood, I think my mom was my biggest influence on my work ethic, and Dennis was my biggest influence on my creative interests. I’m very grateful to both of them.

Dennis and I were great friends from preschool through eighth grade, always working on projects together – writing stories, making comic books, building forts. He lived on a farm.

Somehow, Dennis always had some sort of intel on the next cool music or the counterculture from another era or things like auteur cinema. I really don’t know what his sources were back then, because we didn’t really have the internet. Yet, he’d always be turning me on to some new bit of interesting culture.

When we were younger, we played with legos a lot. I loved legos. I pretty much always asked for legos whenever I thought I might have the opportunity to get a toy for some sort of gift.

My mom would really only get us toys on our birthdays and on Christmas. Although our family didn’t have a ton of money, I think we had enough to get occasional gifts throughout the year. But we didn’t get them. I think this was a really good lesson in self-restraint, anti-consumerism, and not indulging every impulse you have, even if you can. This was pretty cool, in retrospect.

Whenever I got a new lego kit, I’d first build the model according to the instructions. Then, the next day, I’d take it apart and build everything from the photos on the back of the box with no instructions. Then, I’d take it apart and build random stuff, combining pieces from sets with totally different themes.

Dennis and I would make up our own worlds and characters and backstories. But we never really played with the legos once things were built. It was all about creating the worlds and the characters.

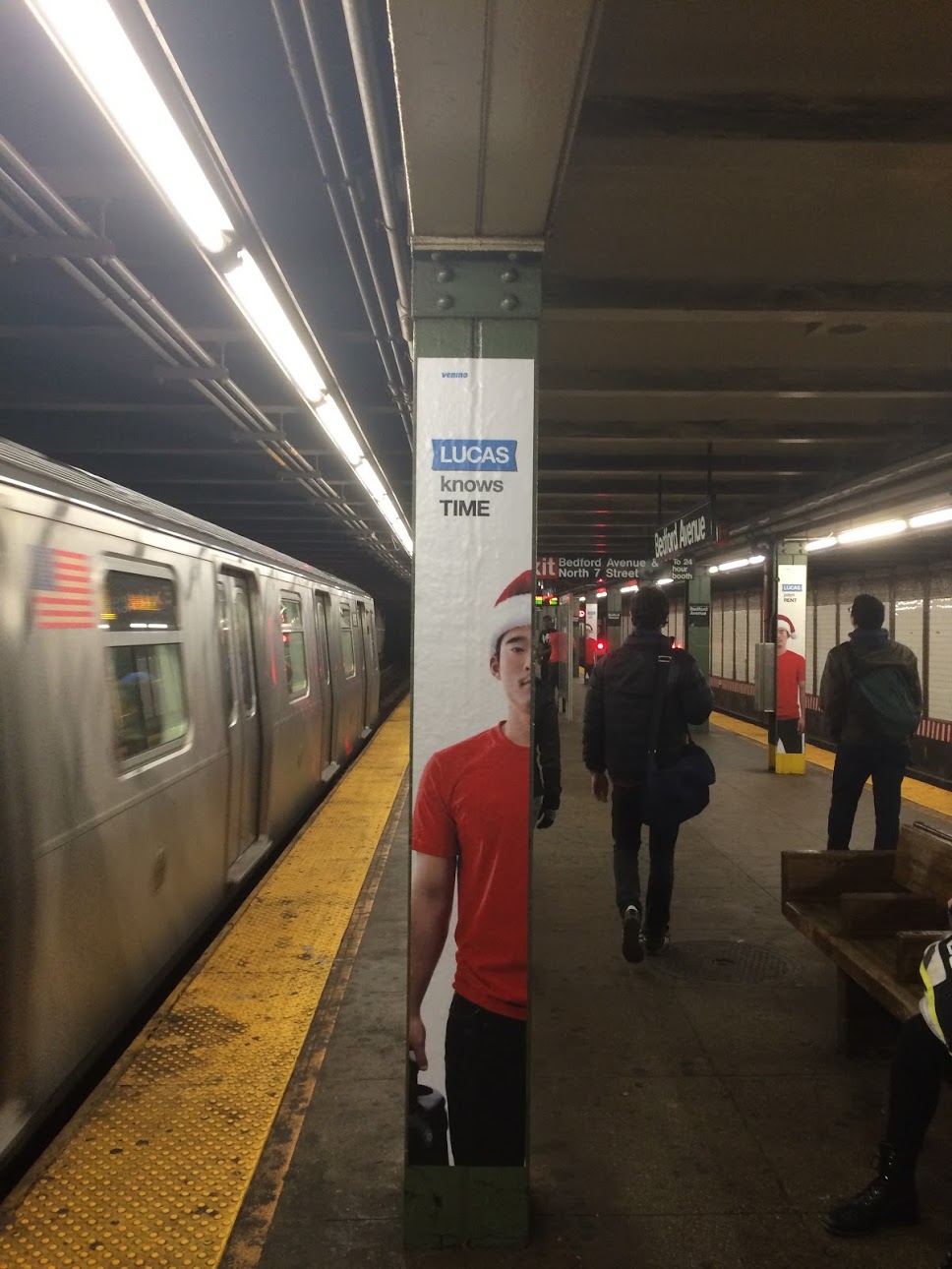

This picture here is a pasting I saw in New York.

I really love street art, for many reasons.

(a) It’s embedded into the drudgery of everyday life – can you think of any time when art is more essential than during your daily commute?

(b) You don’t need any tickets to see street art – it’s a public good. It’s not locked up behind some commercial experience in a museum that most people can’t afford to get into.

(c) There’s no credentialing for street art. Something I’ve noticed whenever I encounter anyone in the professional art and museum scene is there’s a huge amount of credentialing and name dropping, maybe just to convince everyone that the emperor is indeed wearing clothes and that’s why it’s all so expensive.

But this is one of the key lessons I learned from Venmo – money is pure fiction, database transactions, only valuable because people believe it is valuable. This is true of art, as well, and of many other things people value.

I think most people overvalue most things, however. A lot of people I talk to in the Bay Area are terrified of the idea that they could be making slightly more money somewhere else – and these people are all making a ton of money.

Maybe if you came from an upper middle class family, went to a great school, got a great job right out of college – maybe the idea of not having as much money as you have always been accustomed to is kind of scary.

Growing up, my family had a pretty modest amount of money, so I can’t say for sure.

I was lucky to attend good schools, but never really imagined I’d join corporate America. Instead of summer internships I worked construction jobs, because I liked building things. But, I learned on these jobs I didn’t want to work construction as a full time job.

The week I was graduating from college, my mom was visiting me. I remember she asked me what I was going to do after college.

I told my mom I didn’t have to move out of the dorm room for another two weeks, so I had plenty of time to figure things out.

This is the way I have been telling this story for years, James Dean cool. I eventually did say this to my mom, but I remembered as I was preparing this talk that before I said that, I cracked up. I interpreted the question with an existential gravity that got me crying just like I did when my mom told me Santa Claus was a lie that parents told kids. The idea that you figure out “what you are going to do” with your life when you become an adult and enter the “real world” was another fairy tale from childhood.

I ended up getting a part time job at an IT help desk. It paid fifteen dollars per hour, and I worked twenty hours per week. The rest of the time I went door to door trying to sell websites to restaurants, bars, and barber shops.

I had a dirt cheap apartment I shared with my friend Iqram, which barely had enough room for two full size mattresses which we threw directly on the floor. I wish I had a picture of this apartment I could show you. The bathroom was so small that when you sat on the toilet, your leg would be pressing into the wall next to you. It was one of my favorite apartments I’ve ever had. The rent was $425 per month, which we split down the middle, and the location was fantastic.

I had enough money to go to Ten Stone – this bar you see here – and drink beer and play pool every night. On the way home from the bar we’d sing Harry Belafonte songs on the streets. I don’t think I ever had as little income or as many laughs.

The thing I really like about “pool table bars” – as opposed to any other kind of bars, like “cocktail bars” or “dancing bars” – is that they’re really conducive to talking to random people from all walks of life. Most bars you go to, people either all come from a single socio economic class or they have their guard up (probably rightful to be wary of predatory behavior).

But at “pool table bars” – which are often what I also would refer to as “jukebox bars” or “cold beer bars” – the game of pool is the shared interest that gives you the spark of a conversation with anyone.

We met some crazy characters at Ten Stone. We used to play pool til all the bars closed at 1am with this Gulf War vet, then a bunch of us would hop into the bed of his pickup truck with his dog and zoom over to Chinatown to see if we could get the waiter at David’s Mai Lai Wah to indulge us with an after-hours night cap of Black Label and soda (or, at the very least, if he could do us a favor, just some Tsing Taos) with our plates full of long beans and crispy pan fried noodles.

I still love going to pool table bars – they’re some of the few places I think I can go in the Bay Area where I can hear a perspective that someone is not regurgitating from the front page of hacker news. If you have the same information as everyone else, you have no edge.

Eventually, I left that part time job in Philly to join a startup in New York City. The whole time I was working part time, I was also working on a bunch of different startup ideas with Iqram, and eventually we realized we didn’t know anything about building a startup so maybe we should go work at one to see how it was all done.

I had a lot of trepidation about joining a corporation, even a startup corporation.

Every corporation is a machine that is built with the goal of generating predictable returns. The method for accomplishing this is to make the demand for a product and the manufacturing process for supplying it predictable, by systematically eliminating uncertainty and reducing variance.

If this sounds horribly boring and conformist to you, you are right, it is. But using process to eliminate uncertainty is how we achieve stable civilizations. We can build up crop surpluses to avoid famine in the event that a year’s harvest gets destroyed by a hoard of locusts or enable specialization of labor so that scientists can research and develop treatments for diseases.

But most of the benefits of corporations are abstract and removed from the day to day process of the corporation, which in reality can be just as bleak and absurd as the glimpses of it that you get from the outside. My own picture of corporate America – which was only confirmed by what I witnessed at a prestigious undergraduate institution – was based on a few images from my younger years.

There is a priceless scene from the movie The Graduate, where Benjamin gets pulled aside by one of his dad’s friends for an inside tip, some career advice.

Mr. McGuire: I want to say one word to you. Just one word.

Benjamin: Yes, sir.

Mr. McGuire: Are you listening?

Benjamin: Yes, I am.

Mr. McGuire: Plastics.

Benjamin: Exactly how do you mean?

Mr. McGuire: There’s a great future in plastics. Think about it. Will you think about it?

This may sound all too familiar if you substitute “search,” “social,” “local,” “mobile,” “P2P marketplace,” “DTC,” “blockchain,” or “AI” for “plastics.”

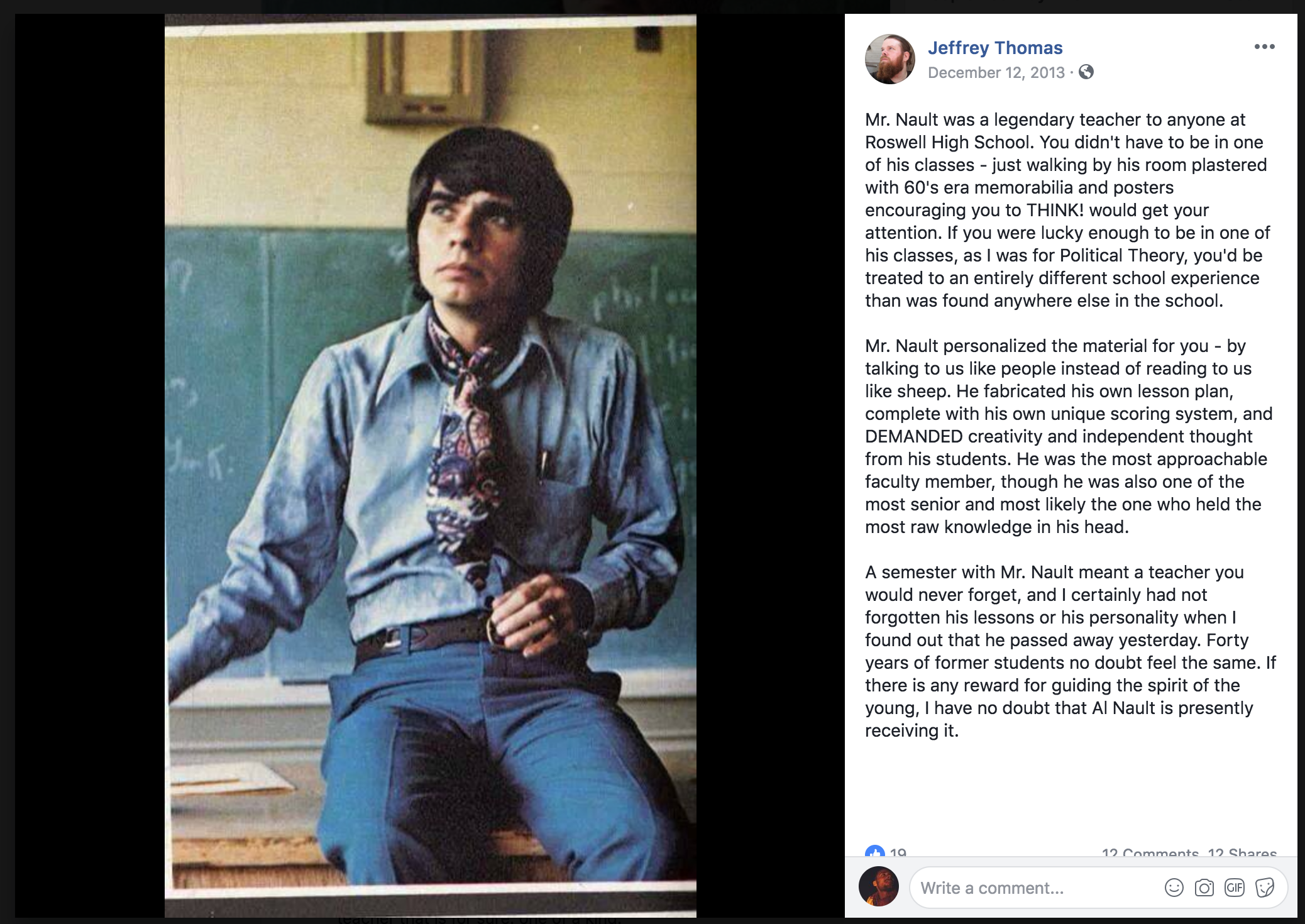

The other knowledge I had about working life came from Mr. Alfred Jay Nault, who taught a Political Theory class I took in high school.

Mr. Nault was my introduction to Nietzsche and to Marx. In his lectures, he would quote passages like this one from Marx:

[T]he raising of wages gives rise to overwork among the workers. The more they wish to earn, the more they must sacrifice their time and carry out slave-labor, completely losing all their freedom in the service of avarice.

When I learned what Marx had to say about labor and capital, I thought to myself, it is better to own the means of production than to work for wages. This has always stuck with me.

The other really important idea I have carried with me from Marxist economics – and this is where I promise I’ll bring it back to the topic at hand – is technological determinism [*].

This is the idea that technology is a force more powerful than any individual participating in building or inventing technology. Technological progress will continue independent of the individuals involved, and things which are efficient and productive will eventually be invented by someone, whether or not it’s you.

Take Venmo, for example. If we had not built Venmo, would there be some other way to easily exchange money with your friends using your mobile phone? Almost certainly.

If you subscribe to technological determinism, and you like building things, it can be a little deflating. Why go through all the effort if someone else would just do this stuff anyway?

None of the companies trying to convince you to work for them will mention technological determinism. They will confirm what your parents and teachers told you, that your work and contribution will be totally unique and significant.

Let’s do a little tour of a few jobs pages of technology companies that I screenshotted last week to see what I’m talking about.

https://www.airbnb.com/careers/departments/engineering

Craftsmanship.

Airbnb makes an appeal to engineers with discerning aesthetics, pitching the virtue of craft.

It is somewhat surprising to see Airbnb taking this angle, because you typically see companies with less scale or a more intangible product or mission pitching the opportunity to learn from experts and master your craft.

While I appreciate craftsmanship, I have always found the obsession with it–like you see in the documentary Jiro Dreams of Sushi–somehow offputting, like the escapism of creating sand mandalas. While my critique of craft is its self-absoprtion, Charlie Kaufman, in this incredible speech I came across a few years ago, argues it’s even more depressing when the product of craft is something you share with others:

I think craft is a dangerous thing. I saw a trailer for a movie, I don’t want to say what the movie is, but it’s coming out soon. And it was gorgeous, it was… gorgeous. And it made me really depressed, and I was trying to figure out why.

I think there was an amazing amount of craft and skill on the part of the filmmakers in this movie. And yet it was the same shit. I know that this movie is going to do really well, and I know that the people who made it are going to get rewarded for it, and so the cycle continues. So I think the danger of craft is that it needs to be in second position to what it is that you’re doing.

It’s seductive to put it in first position, often because what you’re doing is meaningless or worthless, or just more of the same. So you can distinguish yourself by being very, very good at it. I think you need to be willing to be naked when you do anything creatively in film or any other form, that’s really what you have to do because otherwise it’s very hard to separate it from marketing.

Because I recognize that the meditative aspect of craft is an excellent way to cope with meaninglessness, I grow terrified when I start to enjoy a particular type of work that what I’m doing is “just more of the same.”

Build for Everyone.

If you work for Google, you’ll be promoting equality, one of the most popular virtues in the United States.

Help us build the universal payments infrastructure of the internet.

Stripe is selling equality, as well as the allure of working at scale.

https://www.facebook.com/careers/

Do the most meaningful work of your career.

Facebook is selling meaning, but you need to take their word for it, because they don’t mention any specific virtue you’ll manifest when you work there.

IMPACT is another word you hear all over Silicon Valley, in performance reviews and job posts, especially if you’re an engineer. It’s a euphemism for power and another code word corporations use to convince you that your work is meaningful. Silicon Valley’s obsession with power and celebration of impact always seemed to me a little disrespectful to school teachers, single parents, and anyone else working on a smaller scale.

So am I saying that none of these corporations offer opportunities for meaningful work? These things are probably all just as meaningful–or, perhaps more accurately, just as meaningless–as any other things that I or anyone else has ever done.

And while I find the marketing of meaning distasteful, because I don’t think it is something that someone else can give to you, I haven’t worked at any of these corporations, so I can’t really say for sure whether or not they deliver meaning.

What I can talk about is what I have worked on. I can talk about what may turn out to be “my” magnum opus.

That phrase is hard to say, because it is a depressing reminder that my magnum opus is quite likely behind me.

But, it will be difficult to do something more significant than Lucas.

I put “my” in air quotes earlier, because I play a pretty minor role in this story – a facilitator, an editor, or a producer. And, I take some comfort knowing that I am OK with playing a supporting role in what I consider to be my magnum opus thus far.

It was fall of 2013. Venmo had already been acquired by Braintree, and our new parent company was at that moment in talks with Paypal about another acquisition. Braintree had hired this hotshot creative agency to do a big branding / PR / advertising campaign, repositioning the company as the developer centric operating system for payments, or something of that nature.

They had some extra budget and were talking about doing a holiday advertising campaign to promote Venmo. At this time, Venmo had spent zero dollars on paid advertising, and all the growth had been word of mouth.

This agency came back to us with a few proposals, and the leading contender was to buy banner ads on bestbuy.com that prompted you to use Venmo to get paid back when you bought gifts as a group.

I was in our office with Iqram and Neil, our creative director at Venmo. Everyone was dejected and sulking because this ad campaign proposal just didn’t feel right. Iqram said, “If we are going to spend a ton of money on ads, at least we should do something fun, like billboards or taxis.”

Yea, that would be fun, we agreed.

He continued, “Something dead simple. Look at Lucas over there. He makes coffee. Lucas uses Venmo.”

Neil and I looked at each other, excited.

That would be pretty cool.

Neil grabbed Lucas’s photo off of the Venmo team page and photo shopped a Santa hat onto him–I don’t remember at all why. As soon as we had a “Lucas uses Venmo” comp, we hit the streets and started tapping people on shoulder, showing it to them, asking them what they thought. “What the heck is Venmo?”

Bingo.

Our colleague Shira called the MTA on Black Friday to get pricing for the subway ads. There happened to be some inventory available in December, and it was not totally out of the realm of what we were planning on spending on the agency proposal that no one loved.

Since we were in the final stages of acquisition talks with Paypal, we had to get every budget item over one hundred thousand dollars approved. I remember sending Paypal the final assets for approval – they responded, “Where is the rest of it?”

I told my boss, Bill, the CEO of Braintree, that if the company didn’t fund the campaign, I would put it on my personal credit card. I had to see it happen. “You really don’t think we should explain what Venmo is a little bit? … OK, I don’t really get it, but I trust you guys.”

The first ads to show up were the taxi tops. These were expensive, rare to find, and had little effect.

A few weeks later, the subway ads rolled out, a bunch of subway cars and a Bedford Ave station takeover.

I remember walking onto the train platform, down the stairs underneath the huge “Lucas takes the stairs” pasting, and seeing rows of Lucas on the i-beams down either side of the platform: “Lucas loves NYC,” “Lucas runs a mile,” “Lucas pays rent,” “Lucas knows time,” (this last one a head nod to Dean Moriarty and one of the only lines that I contributed).

For me, it felt like walking into a street art cathedral. It was completely unnecessary and uncompromisingly absurd. People found it puzzling, infuriating, hilarious.

Everyone was asking on Twitter and Facebook and Reddit “what the fuck is Venmo?” There were news articles with titles like, “Reviled Venmo Ads Explained.” There were fan sites like lucasloves.com. There were even Lucas meme generators where you could make your own Lucas ads. Some random person hosted a meetup and did a presentation on Lucas. Someone from our team vacationed in Puerto Rico for the holiday and came back reporting people in the pool at his hotel talking about Lucas.

Was any of this meaningful? It’s tough to say, but it was certainly not technologically determined–no one else would have done this except the small group of people behind it. I look back on it fondly and am very grateful to have been a part of it, happy that it brought laughter to many people during their daily commute for a few weeks.

Almost everything about Venmo is surreal to me. For many years many people didn’t even understand what we were trying to do or why you would possibly need to send money to a friend using your phone. They told us to stop wasting our time and move on to something else that people actually wanted.

There are so many moments I can point back to – and many others I cannot recall, I’m sure – where if things had gone slightly differently, there would be no Venmo today. There are many people who did not work at Venmo, people that worked at banks or other partner institutions, who bet on us when every protocol and process in their book said not to, just because they believed we were good people. Venmo would not exist without any of them.

With all of this luck on the one hand, and this idea of technological determinism on the other hand, it is tough to look back with any emotion other than gratitude.

What I am most grateful for, however – more than any of Vemo’s success as a product – is the friends I worked with at Venmo. Some people say don’t work with your friends – this seems crazy to me. I worked with friends at Venmo, and I’m working with friends right now at The Fin Exploration Company. I always want to work with my friends.

We worked really, really hard – 24x7 for many years. We basically lived in our tiny office on 7th Ave, working, eating, drinking, playing, sweating together, sunrise to sunset (often to sunrise again). There’s nothing I know that forms stronger bonds than a hard sprint-marathon of co-working and co-living with a small group of people.

So, I try to spend as much of my time working hard on projects with friends, in my “real” job and outside of it, for fun. And, I’m always wary of these projects regressing to “just more of the same.”

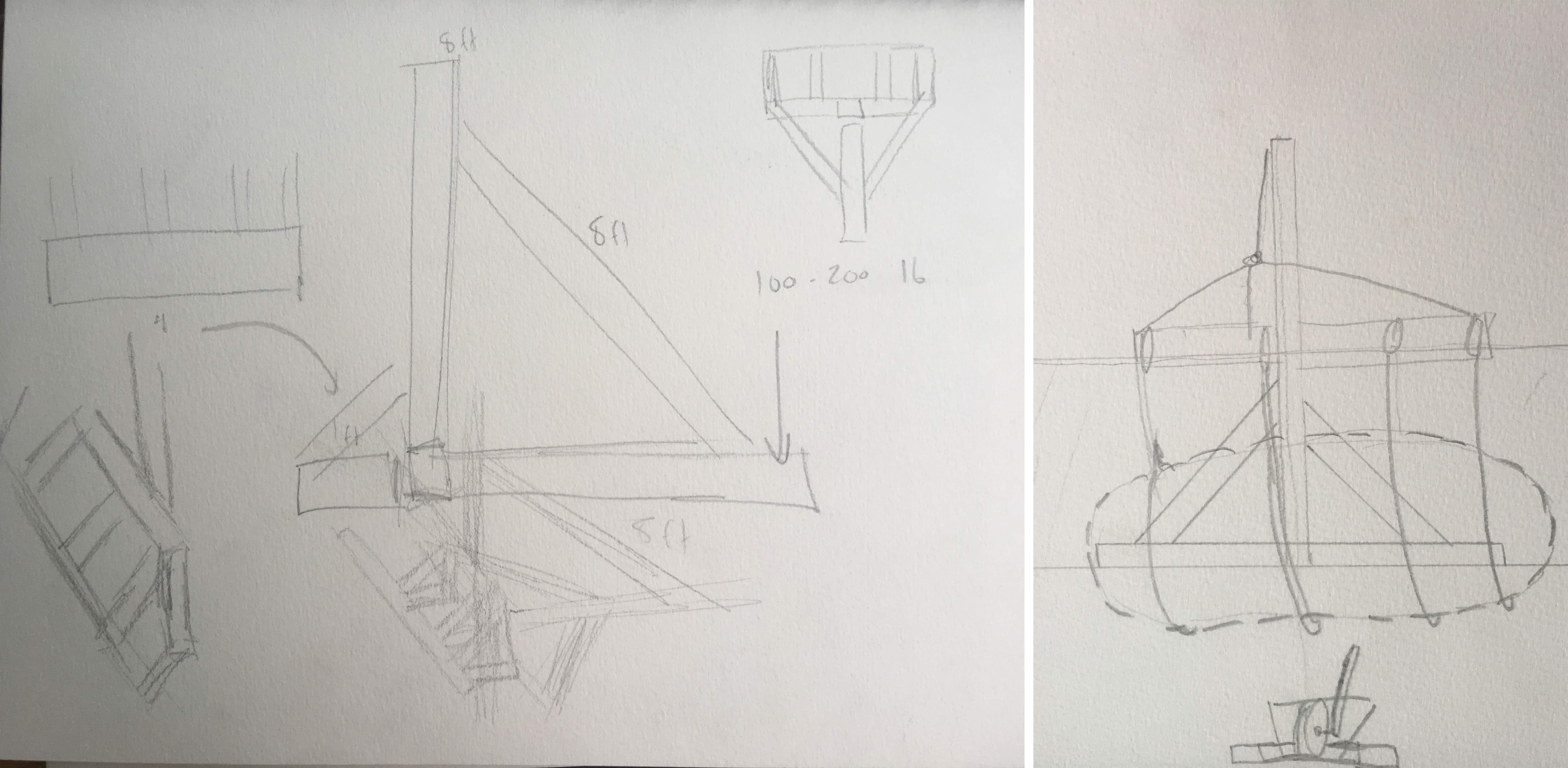

A little while after I moved to California, I was living in a house with 4 friends. In the last week of June, we learned that someone had a friend who made these concrete benches that had radiant heating. My friend Rob and I decided that we must have one on the roof to watch the fireworks on the 4th of July.

The guy who made the benches said the way you would typically do this would be to rent a crane and lift the bench onto the roof from the street. He came to check out the house. Because of the way the roof was peaked in the front, we wouldn’t be able to use a crane.

There was a tiny spiral staircase from the top floor to the roof. He took measurements, and the bench wouldn’t make it up that way either.

Rob and I told him to drop off the bench in our garage the following morning and we’d figure it out. He looked very skeptical, reminded us that the poured concrete bench weighed 300 lbs. He asked us several times if we were sure. “Maybe you can just put it in the backyard,” he texted us after he dropped it off.

We went to Lowe’s that weekend to get supplies: a bunch of decking lumber, ropes, ratchet straps, and one item that was not in our original sketch but which we knew we wanted as soon as we saw it in the ratchet strap aisle: a winch. This proved to be critical.

Here is a diagram of the crane we built. We didn’t buy enough lumber at Lowe’s, so we scavenged some 4x6s we had seen on the street a block away earlier that day.

Once we had it set up, we called a few friends to ask them to come help out with the guide ropes we attached to either end of the spreader bar. (A spreader bar, we learned from the bench guy, is a beam that distributes the weight of the bench evenly, so the load does not all get born at a single point.) Our friends would also have to use these ropes to pull the bench away from the house in order to clear the bottom lip of the second floor window – this would be one of the riskiest parts of the operation.

I started manning the winch, and there were a bunch of those squeaks and pops that happen as a wooden structure settles under full load for the first time. Nothing snapped (which was comforting, as we had not done a free body diagram to ensure it would handle all of the forces, tensions, torques, and such).

As we slowly hoisted it up, some neighbors adjacent to us came outside and yelled, “What are you doing with that winch there?”

“Bringing this cement bench up onto the roof. It’s heated!”

“Oh…” They went inside, came back out with beers and lawn chairs, sitting down to watch. I got the feeling they were watching for the same reason you might watch NASCAR.

The rope on the winch was not long enough for the haul, so we had a second climbing rope attached to the bench which was knotted every 15 ft, with a carabiner at each knot. This worked sort of like a drive train, and each time we got a carabiner up to the peak, we had to do this shimmy where I attached a ratchet strap to the carabiner while the winch was also attached. Then I connected the ratchet strap to the deck railing, took all the load onto the ratchet, released the winch, lowered the end of the winch rope down to the next carabiner, attached it, took the load back onto the winch, released the ratchet strap, then wound the winch again to lift up the next segment.

We had to do 4 or 5 iterations of this.

When we finally got the bench over the edge of that glass wall at the edge of the roof without destroying anything or seriously injuring anyone, the neighbors cheered and toasted us with their beers.

I think the only time I sat on the heated bench was the 4th of July and maybe one other time after that.

It wasn’t until years later that I saw Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo, the story of a man who wants to build an opera house in the jungle of Peru.

He first needs to make a fortune to pay for the opera house, so he hatches a plan to harvest rubber from the only remaining parcel of unclaimed land with rubber trees. This land has not yet been farmed, because it is cut off from boat access by a long section of rapids. He gains access to the virgin forest by portaging the massive steam ship over a mountain with a small army of natives, some railroad tracks, and a winch.

I, of course, loved this story.

I don’t love when technologists brand their products as “magical experiences.” This language is disempowering to the recipients of the “gifts of technology,” warning them to not even attempt to understand how things actually work. This tactic, long used by priests, shamans, witch doctors, and mystics, has now been adopted by technology corporations.

My friend Sam has this saying that, to the contrary, “Nothing is rocket science, even rocket science.”

This is one of those things I think you learn as you get a bit older. The same people that told you stories about Santa Claus are the people doing rocket science, the people running the largest corporations, the people running the government, the people shaping much of the world.

They’re probably not any more capable than anyone in this room – in fact, many of the people running the world are probably less capable than most of the people in this room.

Now, I don’t want to knock the rocket scientists – they are smart, and they work really hard. But I think it mostly comes down to hard work, grit, and lots of luck.

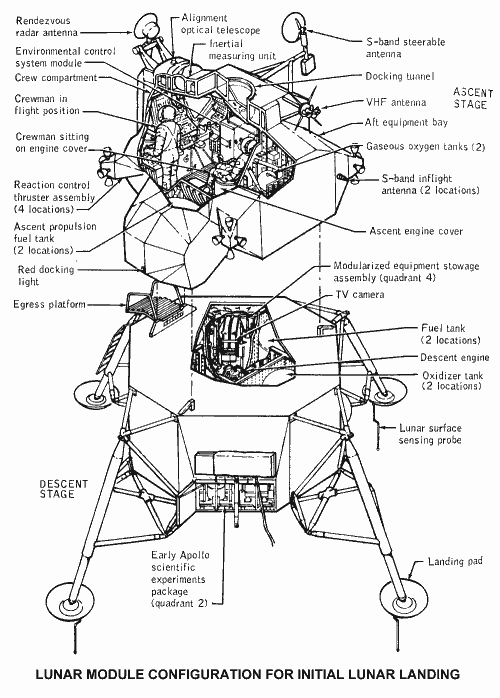

I recently saw a film you could say is about rocket science – First Man. It’s the story of Neil Armstrong and the Apollo 11 Mission to land on the moon.

I just heard an interview with the director, Damien Chazelle, where he says that demystifying space technology was part of his intention with the film:

It was one of the big things I wanted to try to get across because I think we almost take the moon landing for granted today. And maybe it’s because the sort of image of NASA at that time and that we’ve lived with since was this sort of high-tech image you describe and this kind of image of sort of the epitome of technology and the epitome of individuals, this idea of superheroes, basically, walking among us, who did these deeds that were almost easy for them because they were just so super-heroic. And I think it’s much more interesting to think of these people as ordinary human beings working with the limited technology that they had, you know, scrounging things together, figuring stuff out, fixing things with Swiss army knives, doing calculations with pencils and paper.

All of Chazelle’s films are in a way about the pursuit of the sublime. Engineers and astronauts in First Man pursue the technological sublime. The characters of Whiplash and La La Land pursue the artistic sublime.

Unlike the jobs pages we looked at earlier, which tell you that you can get there while enjoying the most cushy benefits packages in the world, Chazelle’s films show a path to the sublime that involves extreme sacrifice, typically the sacrifice of all of your friend and family relationships. Chazelle rings more true to me.

There’s this scene in First Man where one of the practice missions starts going wrong, so NASA kills the live radio broadcast, which the families of all the astronauts were listening to.

Janet Armstrong (Neil’s wife) storms into the NASA control room, demanding they turn back on the radio broadcast so the families can continue getting updates. One of the program directors tells her they have everything under control, and she spits back:

“You’re a bunch of boys making models out of balsa wood! You don’t have ANYTHING under control.”

If you see the equipment that these guys used to get to the moon, this balsa wood analogy is not too far from the truth.

Many critics of space exploration expenditures would agree with her caricature of NASA as “boys making models” – you could argue that space exploration does seem a bit like gratuitous boys’ play when there are still so many problems unsolved back on earth.

Here are some bits of JFK’s speech addressing the critics and articulating the justification for the mission:

But why, some say, the moon? Why choose this as our goal? And they may well ask why climb the highest mountain? Why, 35 years ago, fly the Atlantic? Why does Rice play Texas?

I absolutely love that JFK suggests that the motive for trying to land astronauts on the moon is similar to the answer to “Why does Rice play Texas?” This mission will be one of the most significant things mankind has ever achieved, but at the cosmic scale, landing on the moon holds the same significance–and insignificance–as a college football game.

After acknowledging the absurdity of it all, he continues:

We choose to go to the moon. We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win…

He sounds existentialist: “We choose to go to the moon.” Why should we choose to do hard things? “[N]ot because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills.”

In this speech, he also directly addresses technological determinism:

The exploration of space will go ahead, whether we join in it or not, and it is one of the great adventures of all time, and no nation which expects to be the leader of other nations can expect to stay behind in the race for space.

Here, he again suggests that the moon landing is worth doing simply because it is one of the “great adventures of all time.” But, he also warns that if the United States does not pursue the exploration of space, someone else will. He continues,

For space science, like nuclear science and all technology, has no conscience of its own. Whether it will become a force for good or ill depends on man, and only if the United States occupies a position of pre-eminence can we help decide whether this new ocean will be a sea of peace or a new terrifying theater of war.

JFK responds to technological determinism by presenting a moral choice to the individual (not unlike his “ask not what your country can do for you” rhetoric). Because technology “has no conscience of its own,” the reason for good people to participate in its progress is to make sure that bad people don’t master new technology first and use it for ill.

JFK’s moral imperative is brilliant, the best response to technological determinism I have heard.

Some days, in pursuit of technological progress and control of the means of production in Silicon Valley, I like to think that I’d make good decisions and would be a good steward of technology, steering it towards being a “force for good” and not for ill.

Other days, I realize the supreme convenience of this rationalization of the pursuit of technological power.

And other days still, I think about the insignificance of either point of view on the cosmic scale.

I think a lot about this sort of stuff, about what’s a worthwhile way to spend my time. I write a lot about whether there really is any dignity in work, or whether the dignity of work is just a useful myth.

It can be a little maddening, mentally looping through meaning and meaninglessness.

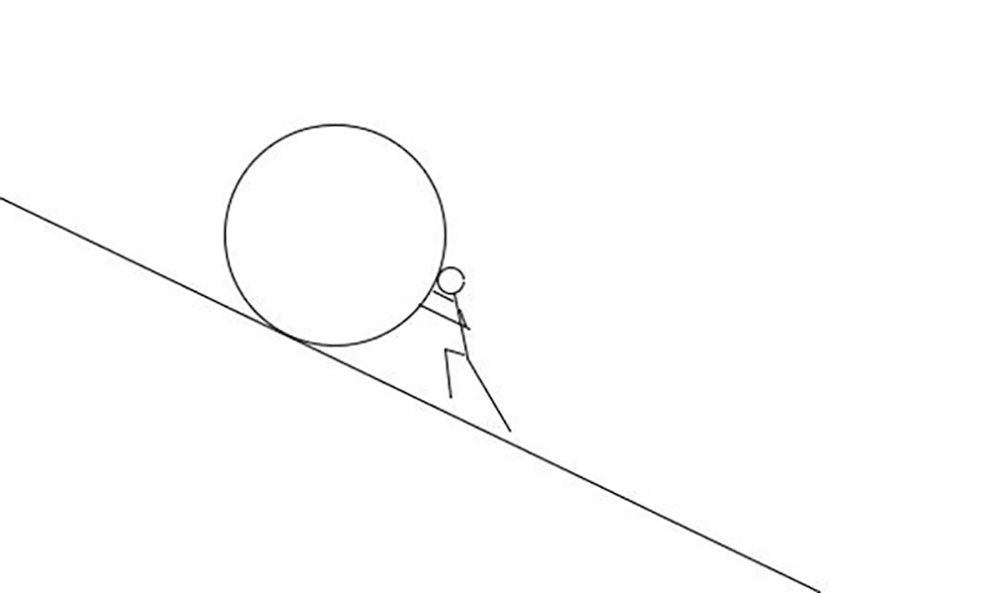

I find myself returning often for comfort to Camus’ The Myth of Sisyphus, his treatise on whether the meaningless of life merits suicide.

I’ll conclude this evening with one of my favorite passages from Camus:

The gods had condemned Sisyphus to ceaselessly rolling a rock to the top of a mountain, whence the stone would fall back of its own weight. They had thought with some reason that there is no more dreadful punishment than futile and hopeless labor.

….

You have already grasped that Sisyphus is the absurd hero…. His scorn of the gods, his hatred of death, and his passion for life won him that unspeakable penalty in which the whole being is exerted toward accomplishing nothing. This is the price that must be paid for the passions of this earth.

….

If this myth is tragic, that is because its hero is conscious. Where would his torture be, indeed, if at every step the hope of succeeding upheld him? The workman of today works everyday in his life at the same tasks, and his fate is no less absurd. But it is tragic only at the rare moments when it becomes conscious. Sisyphus, proletarian of the gods, powerless and rebellious, knows the whole extent of his wretched condition: it is what he thinks of during his descent. The lucidity that was to constitute his torture at the same time crowns his victory. There is no fate that can not be surmounted by scorn.

….

There is no sun without shadow, and it is essential to know the night.

….

I leave Sisyphus at the foot of the mountain! One always finds one’s burden again. But Sisyphus teaches the higher fidelity that negates the gods and raises rocks. He too concludes that all is well. This universe henceforth without a master seems to him neither sterile nor futile. Each atom of that stone, each mineral flake of that night filled mountain, in itself forms a world. The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.