Update: see also my follow-up to this post, Principles for Radical Tax Reform.

In Kinky Labor Supply and the Attention Tax, Namrata and I explored why a state might levy a tax on the sale of human attention to stimulate economic productivity. Here, I’ll explore how a tax on the purchase of human attention might resolve one of the key issues at stake in the ongoing debate about how the government should regulate free speech: the purchase of mass distribution and the conversion of financial capital into social/attention capital and political capital. The proceeds of this proposed tax on the exercise of power would be distributed pro rata to citizens, so that exercise of economic power would directly result in redistribution of that power.

Background

The US government has long sought to mitigate the imbalances that result from the fungibility of financial capital and social capital. For example, because candidates that get the most tv and radio airtime will have an advantage in political campaigns, the FCC regulates Political Broadcasting, requiring that broadcasters provide reasonable access to all candidates for federal office to purchase airtime, that they provide equal opportunities to all candidates in purchasing airtime, that they charge all candidates the same rates, etc.

There also has been much political debate around campaign spending more broadly, under the premise that allowing unrestricted spending on political campaigns gives an unfair advantage to the wealthier candidates competing in an election. In an attempt to remediate this concern, the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 required disclosures of contributions to federal campaigns and an amendment to it placed limits on campaign contributions and expenditures. Subsequent supreme court cases citing the first amendment, however, found some of these restrictions unconstitutional. Buckley v. Valeo ruled expenditure limits contravened the first amendment because they restricted “quantity of expression,” Citizens United v. FEC held that restrictions on corporate spending on “electioneering communication” were unconstitutional, and McCutcheon v. FEC held that aggregate limits on political giving by an individual are unconstitutional. These rulings all protect the ability to trade financial capital for political power.

In the age of the internet, where every citizen is equipped with a device that allows them to freely publish content accessible to the entire world at any moment, you might wonder whether the balance of power has shifted back towards the people, away from the wealthy and large corporations. This has not proved to be the case: while it is cheaper and easier than ever for individuals to publish, it is also still possible to pay for increased distribution, so mass audience still tends to mirror the distribution of financial capital, where those that spend the most money garner the most attention.

Distribution of Power in Networks

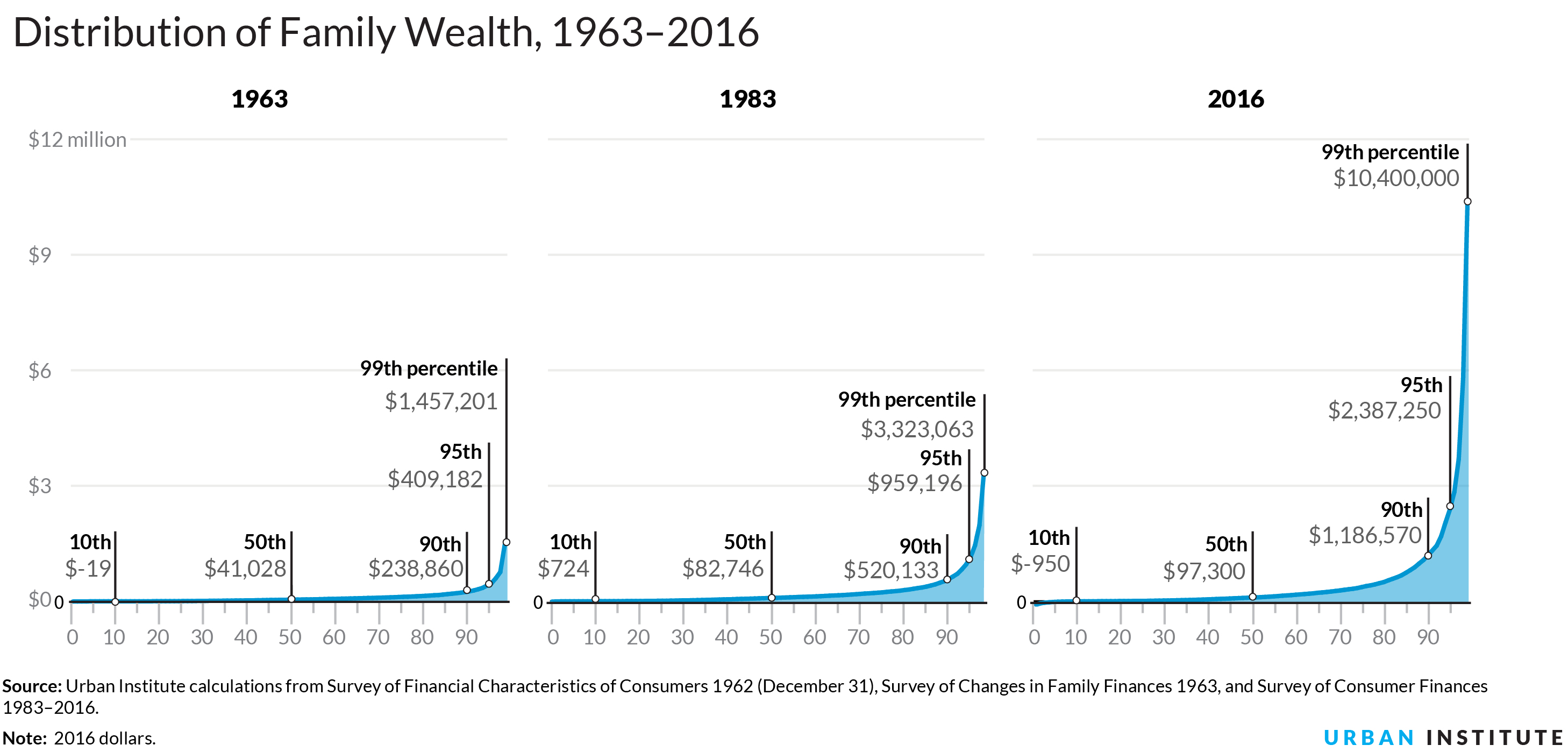

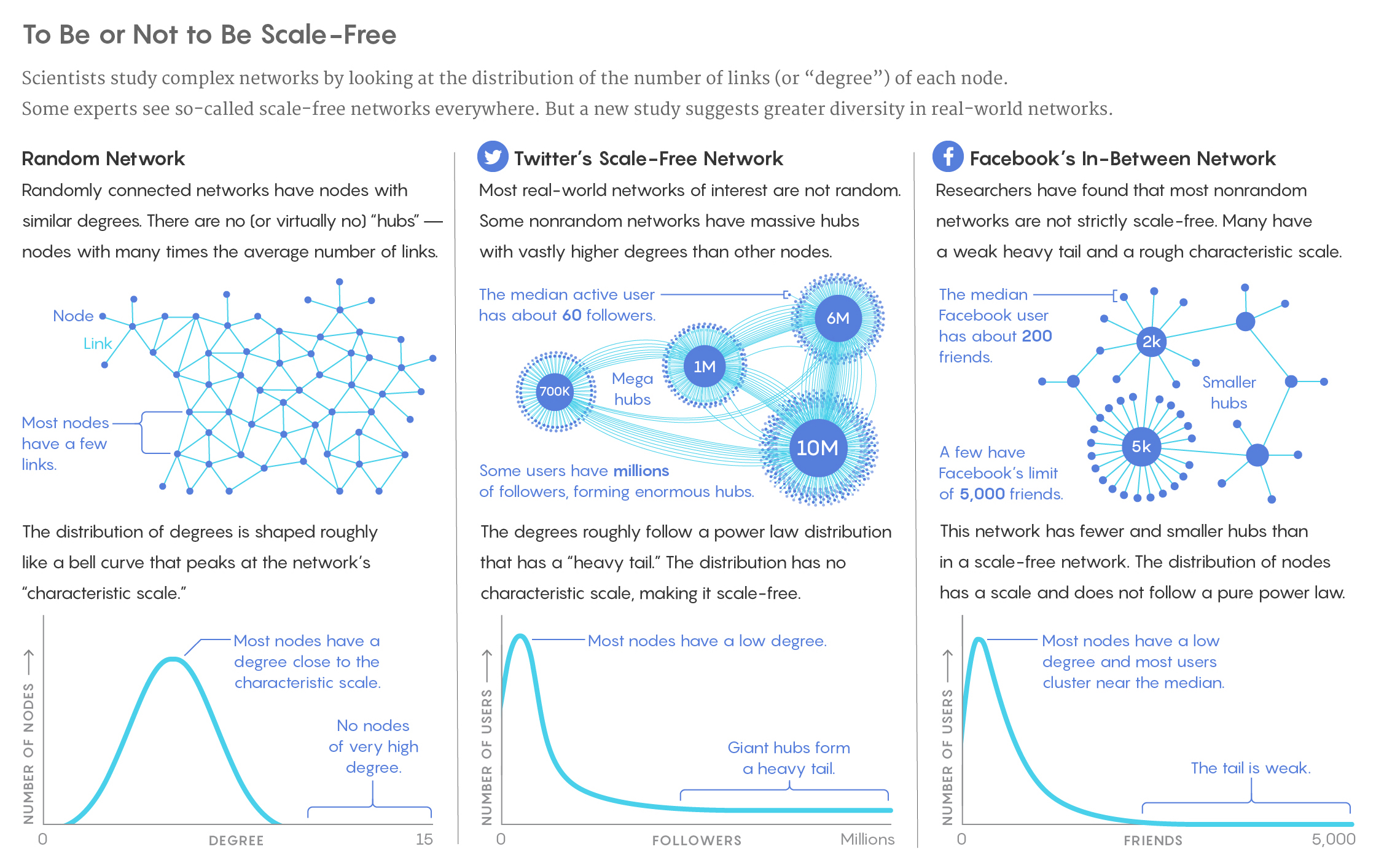

The distribution of power across networks tends to follow Pareto distributions (colloquially “power laws”), with the classic example being that “80% of the wealth of a society is held by 20% of its population.”

The distribution of social capital (ie follower count) in social networks reflects similar network dynamics and results in a similar distribution of power: while there certainly are cases of outliers organically building massive followings on the new distribution platforms enabled by the internet, a disproportionate amount of the cumulative attention is commanded by only a small number of participants with massive followings (or, by those that spend the most on boosting their reach via advertising):

The compounding nature of capital in each of its forms drives these distributions. Wealth compounds by earning interest on itself. Social followings compound as your followers share your message with their own networks, and then those networks re-share, etc.

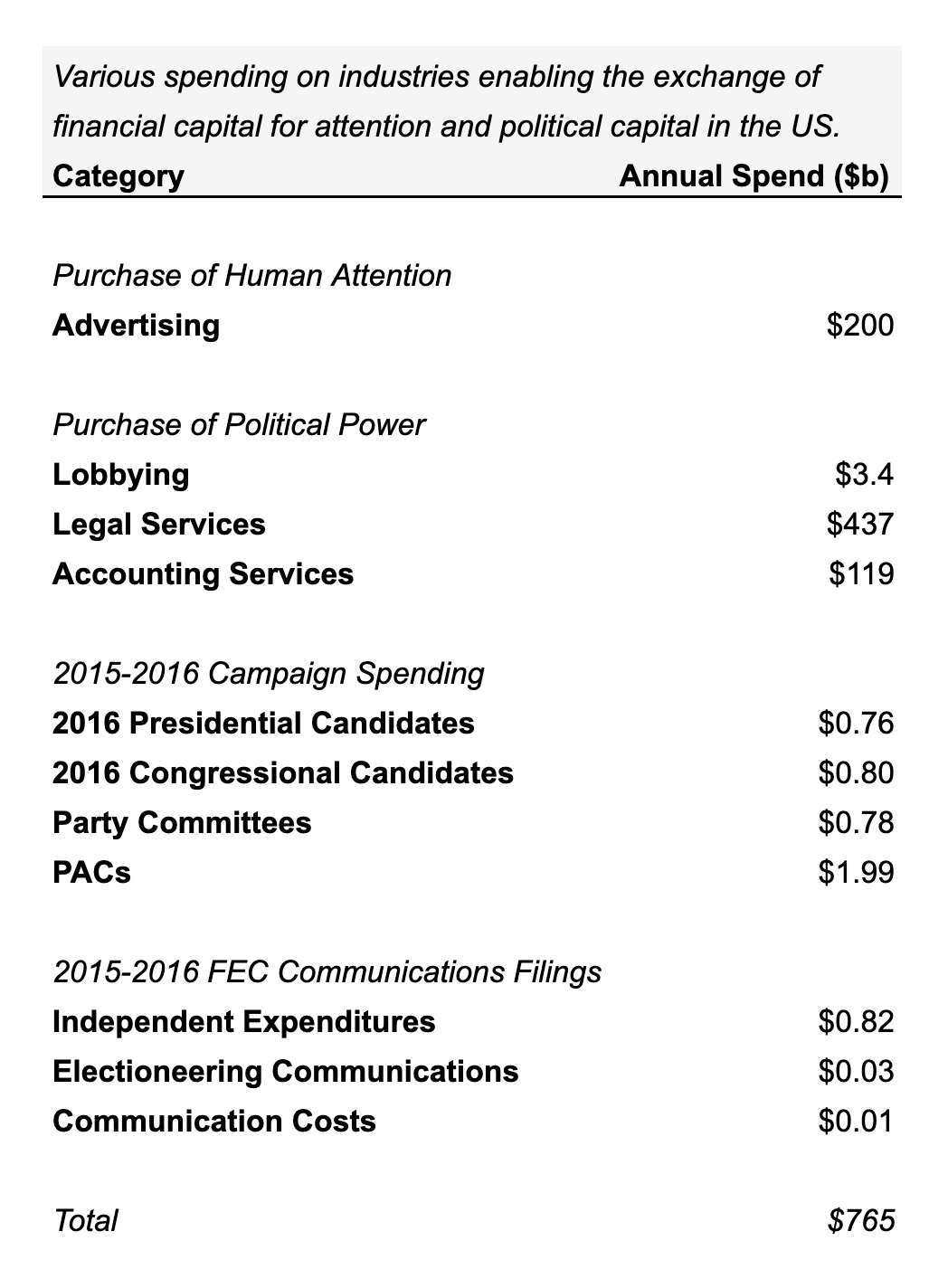

To get a sense for just how much money is deployed each year converting financial into social and political capital, a good proxy for the lower bound of direct purchase of political capital is the $3.4 billion annual spend on lobbying in the US, while the total amount of financial capital converted to all forms of social / attention capital is the ~$200 billion annual spend on advertising in the US.

A “Power” Tax on the Purchase of Human Attention

An idea for counterbalancing the power laws that arise in networks that has been on my mind since reading Posner and Weyl’s Radical Markets and related papers on quadratic voting involves the word play in their use of “radical.” In politics, “radical” is commonly used to describe movements promoting dramatic overhaul of the current structure; in math, however, the “radical” is the root function (eg, square root x), which inverts a power function (eg, x squared, the “quadratic” function).

Posner and Weyl propose quadratic voting as an alternative to one-person-one-vote that might enable a more accurate expression of group preferences and guard against tyranny of the majority by allowing voters to purchase multiple votes with “voice credits” where purchasing more votes becomes quadratically more expensive with each additional vote purchased.

As a category, however, I think radical functions present a fertile area to explore for counterbalancing all of the power dynamics that naturally occur in networks.

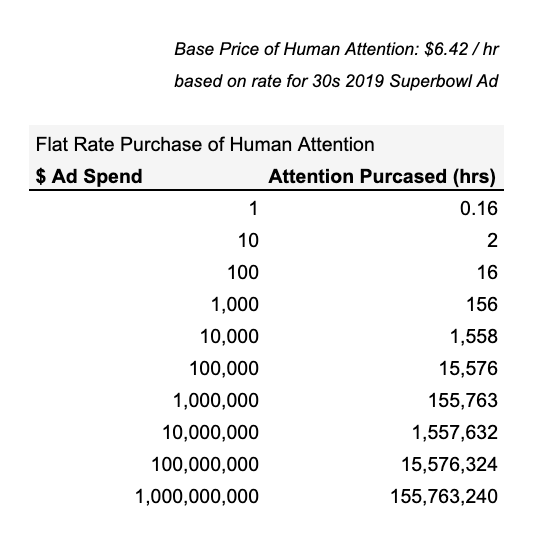

Consider the sale of human attention during the 2019 Super Bowl. CBS charged $5.25mm for each 30s ad aired to 98.2mm users. This works out to a rate of $6.42 per hour of human attention purchased.

At flat rate pricing, a single individual or corporation could buy attention according to the following schedule:

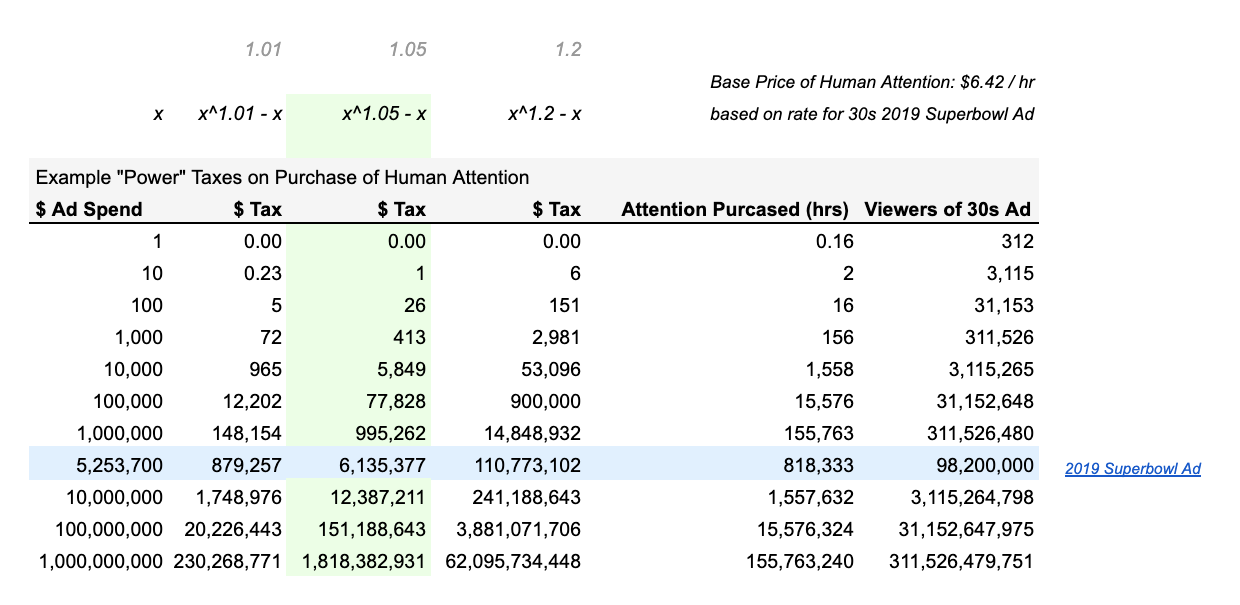

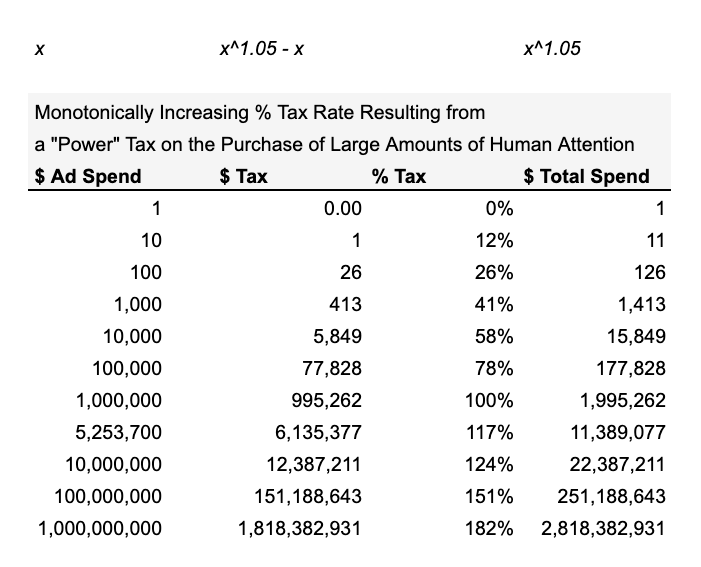

Now, let’s imagine a tax where we markup every dollar spent by a single buyer using a power function, such that when your annual spend on advertising is $x, a tax of $x ^ 1.05 - $x increases the fully loaded annual cost (including tax) to you to $x ^ 1.05.

To see how this is a radical tax, consider the inverse: when you spend $y on advertising + tax,

you only receive $1.05√y worth of human attention at market rate (the

radical in this formulation is 1.05).

This use of 1.05 as an exponent / radical is a somewhat arbitrary one I chose after comparing a bunch of different exponents for the power function, where the marked up price is x ^ exp (and the tax or surcharge is x ^ exp - x):

My only methodology for the setting exp to 1.05 was that I kind of liked the way works out, where when you spend ~$5mm you pay an additional ~$6mm in taxes on top of that. (I have a hunch that hunting for exp in the 1.05 to 1.2 range might make sense, but I’m sure there is a more rigorous way to arrive at the appropriate exponent based on factors like the current population, level of economic disparity, interest rates, and magnitudes at which you want the purchase of human attention to start to become prohibitively expensive).

A few points of interest. (i) Because this is a sales tax, not an income tax, there’s no reason it can’t exceed 100%. (ii) Unlike a graduated progressive tax where the % tax increases at certain steps or thresholds, every marginal dollar spent under this scheme results in an increase in the % tax:

The more capital a single entity deploys in advertising, the higher the effective tax rate. I think this is a pretty elegant way to offset the advantages of compounding interest.

As I envision this scheme,

- All of the tax proceeds generated would be distributed per capita to citizens (so the govt wouldn’t have to do all the work to figure out how to effectively deploy this capital… think of it as a way to bootstrap basic income)

- The spend,

x, for each entity, would be calculated annually by summing the total amount spent that year on advertising, marketing, lobbying, political contributions, and any other sort of trade of dollars for eyeballs or political power. Addendum: I realized after writing that all legal fees and accounting services should be included as purchasing political power, as these are essentially the ways that you can pay to de-risk chances of getting caught breaking the law (eg, reduce odds you get caught cheating on taxes).

So more power you exert by trading wealth for attention, the more you simultaneously redistribute wealth.

You might think either think of this as a sales tax on the purchase of human attention, or as a new kind of tax levied on the exercise of power (vs a tax on the accumulation of power, like an income tax).

Here is a brief summary of some of the various spending happening in the US, facilitating the exchange of economic power for attention and political capital:

Takeaways

The right to free speech is essential to the functioning of a healthy democracy so that citizens can critique the inequities and failures of the existing regime and laws, but the ability to trade money for attention presents a real threat to democracy, particularly under conditions of extreme (and increasing) economic disparity.

Given the deluge of recent problems stemming from our relatively unregulated rights to free speech on the internet, the natural reaction of many will be to swing the pendulum away from free speech, clamping down on these rights. But it is dangerous to address the challenges that free speech poses to the maintenance of public order in a democracy by conceding too much power to the state to regulate free speech, because this may lead to the state’s ability to silence critics (and, ultimately, to the loss of the sovereignty of the people). So, when we seek to place limits on the fungibility of economic for political power, rather than transferring the reclaimed power to the state, we should engineer a solution that bypasses the state and transfers power directly back to the citizens.

A few words of wisdom from history to mull over in closing…

IAM PRIDEM, EX QUO SUFFRAGIA NULLI / UENDIMUS, EFFUDIT CURAS; NAM QUI DABAT OLIM / IMPERIUM, FASCES, LEGIONES, OMNIA, NUNC SE / CONTINET ATQUE DUAS TANTUM RES ANXIUS OPTAT, / PANEM ET CIRCENSES

Already long ago, from when we sold our vote to no man, the People have abdicated our duties; for the People who once upon a time handed out military command, high civil office, legions — everything, now restrains itself and anxiously hopes for just two things: bread and circuses.

-- Juvenal, Satires

The steam engine, the multiple press, and the public school, that trio of the industrial revolution, have taken the power away from kings and given it to the people. The people actually gained power which the king lost. For economic power tends to draw after it political power; and the history of the industrial revolution shows how that power passed from the king and the aristocracy to the bourgeoisie. Universal suffrage and universal schooling reinforced this tendency, and at last even the bourgeoisie stood in fear of the common people. For the masses promised to become king.

Today, however, a reaction has set in. The minority has discovered a powerful help in influencing majorities. It has been found possible so to mold the mind of the masses that they will throw their newly gained strength in the desired direction. In the present structure of society, this practice in inevitable. Whatever of social importance is done today, whether in politics, finance, manufacture, agriculture, charity, education, or other fields, must be done with the help of propaganda. Propaganda is the executive arm of the invisible government.

-- Edward Bernays, Propaganda

QUIS CUSTODIET IPSOS CUSTODES

Who will watch the watchers?

-- Juvenal, Satires

Beware that, when fighting monsters, you yourself do not become a monster… for when you gaze long into the abyss, the abyss gazes also into you.

-- Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil

Update: see also my follow-up to this post, Principles for Radical Tax Reform.