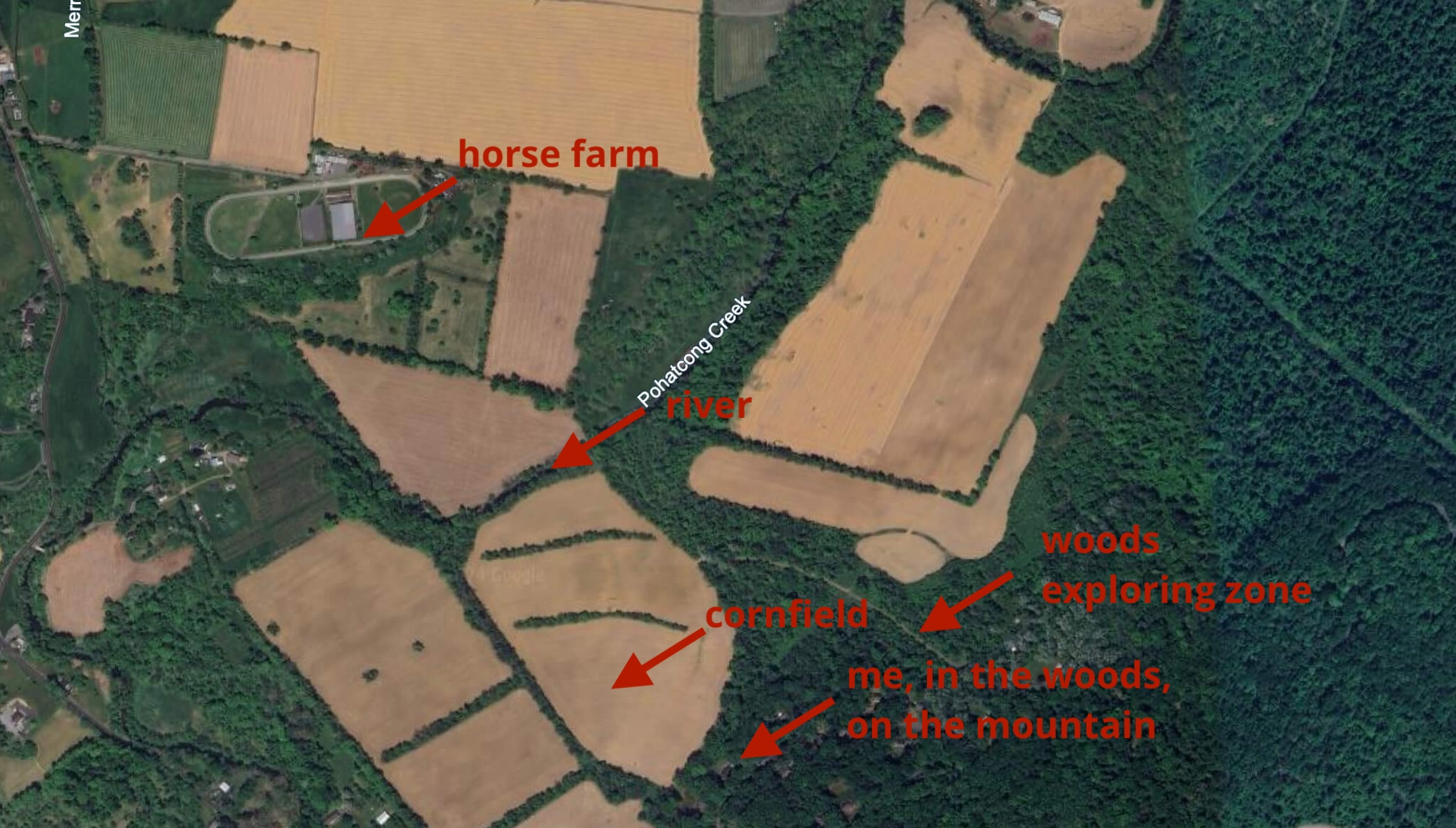

Map of Stewartsville, NJ.

Map of Stewartsville, NJ.

I grew up in a rural part of northern New Jersey in a small town named Stewartsville. In my elementary and middle school there were about twenty kids per grade. We had teachers who called water “wooder.”

My house was up in the woods, on the side of a mountain road. We had about an acre of property. Behind our woods was a cornfield. Behind the cornfield was a river. And behind the river was a horse farm.

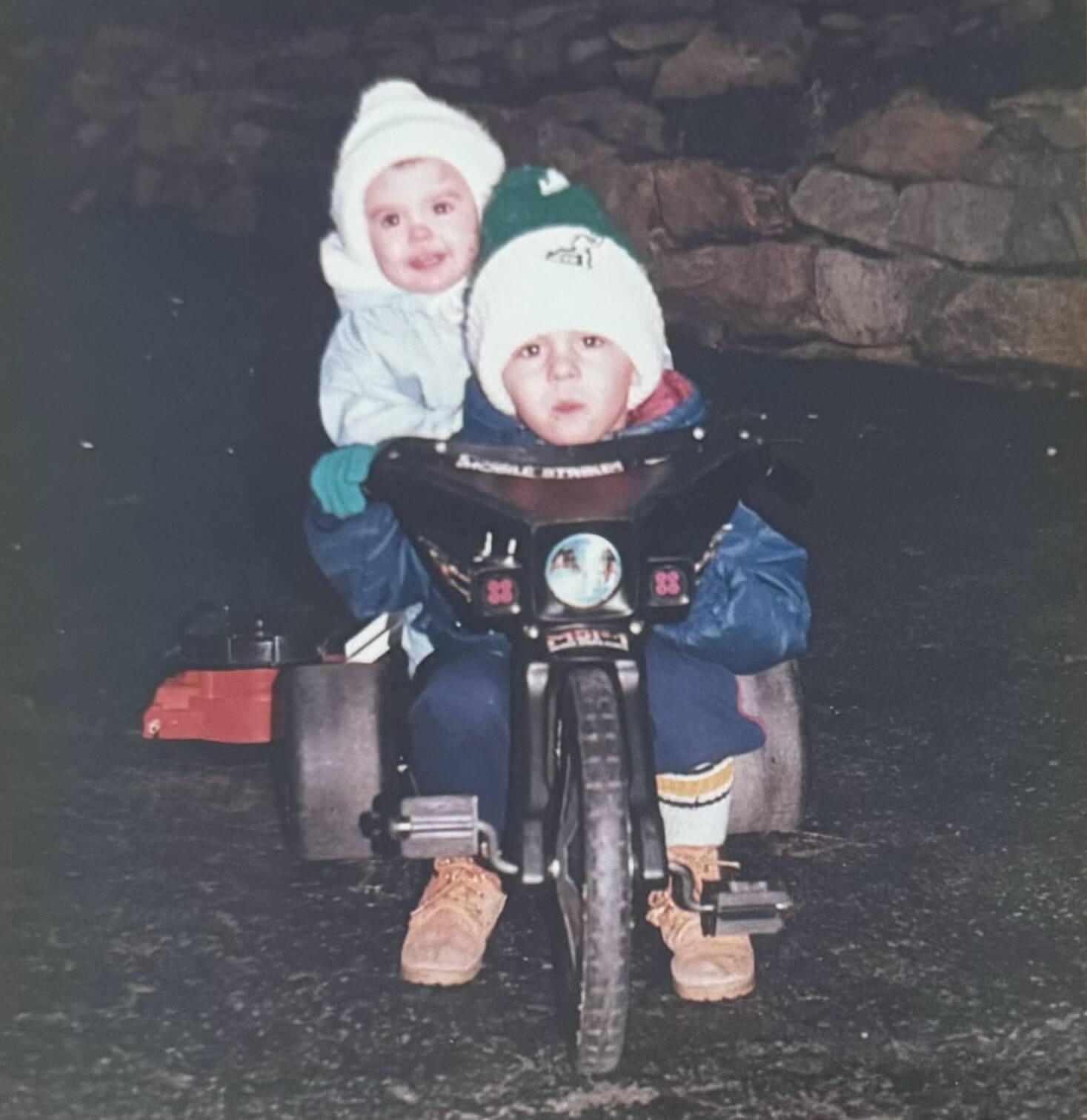

Me and Jenny.

Me and Jenny.

Growing up, my mom worked two jobs, and I spent a ton of time playing with my sister, Jenny. Whenever it was even close to nice weather outside, my mom – if she was home – would say to us:

You don’t get many days like this one. Go outside and play.

So we’d go out to the woods, which were great for adventures – building forts, climbing trees, exploring the forest. We played Robin Hood and cops and robbers and Indiana Jones and games I’m forgetting.

I remember days when I was very young, when someone in the neighborhood would throw a potluck party for the Super Bowl or a Mike Tyson fight or something like that. Five or six families – all with kids – would be there. And after dark, all the kids would go outside to play capture the flag.

I loved playing that capture the flag (1) because it was a pretty fun game, and (2) because it was rare we got together that big of a group for any sort of game.

Co-op bike – er, trike – ride.

Co-op bike – er, trike – ride.

As my sister and I got older, a lot of people with kids moved out of the neighborhood, and the two of us got really into mountain biking.

Beater bike, falling apart.

Beater bike, falling apart.

This pic is a little before we got “real” mountain bikes, but even with these little beater bikes – which I think we had until I was at least in sixth or maybe even seventh grade – we started carving up our property into some pretty serious bike trails.

We cleared huge swaths of undergrowth and trees. We built ramps and jumps out of dirt and wood. We found an old twelve by twelve – leftover from someone’s deck build – and a fairly straight piece of tree that was also about the same diameter. We combined these with some old plywood and boards we cut out of an old wooden pallet to make a very serious bridge over a very dainty little creek at the bottom of the hill where all the sewer pipes from the road ultimately drained.

I don’t remember how much time we spent working on these trails, but it was a lot – I would say we spent well over fifty percent of our time building the trails versus actually riding on them.

I think that’s because a lot of the fun was in building the trails. We got to design them, and once we started building them, surprising and unique problems would interrupt us and call for a novel solution. Once, a tree blocked our way. I thought it would take a few hours to remove it, but it took a few days.

Riding the trail was fun, too, of course, but just not engaging in the same way.

Sleddin’ time.

Sleddin’ time.

We had a similar routine with sledding. Whenever it snowed, we’d build what my dad fondly recalls as “the bobsled run.”

There was a very steep hill down one side of our property, and we would clear a run from the street at the top of the hill all the way down to the bottom of the hill below our house. About three quarters of the way down the hill, there were some Rhododendron bushes planted along the side of the house. In front of these bushes, a little stone wall elevated the garden. We’d pack a ton of snow against this wall to build a “bank turn.” And just to make sure it was nice and fast, my dad would usually give the wall a little spray of hose water to really ice the thing up.

Red-orange sled.

Red-orange sled.

We’d take one of these red-orange plastic sleds up to the street, and then barrel down the hill, hit the bank turn at top speed, and head for the final feature of the run – a five foot cliff that launched you into the woods and pretty much right into some huge trees.

If you slammed into a tree – which we did every season – the front tip of your plastic sled would get damaged. It would fold down and bend underneath the sled in a way that really began to hamper your top speed, so we had to get new sleds from Laneco every season. Looking back, I’m a little surprised it also didn’t land us in the hospital or the morgue.

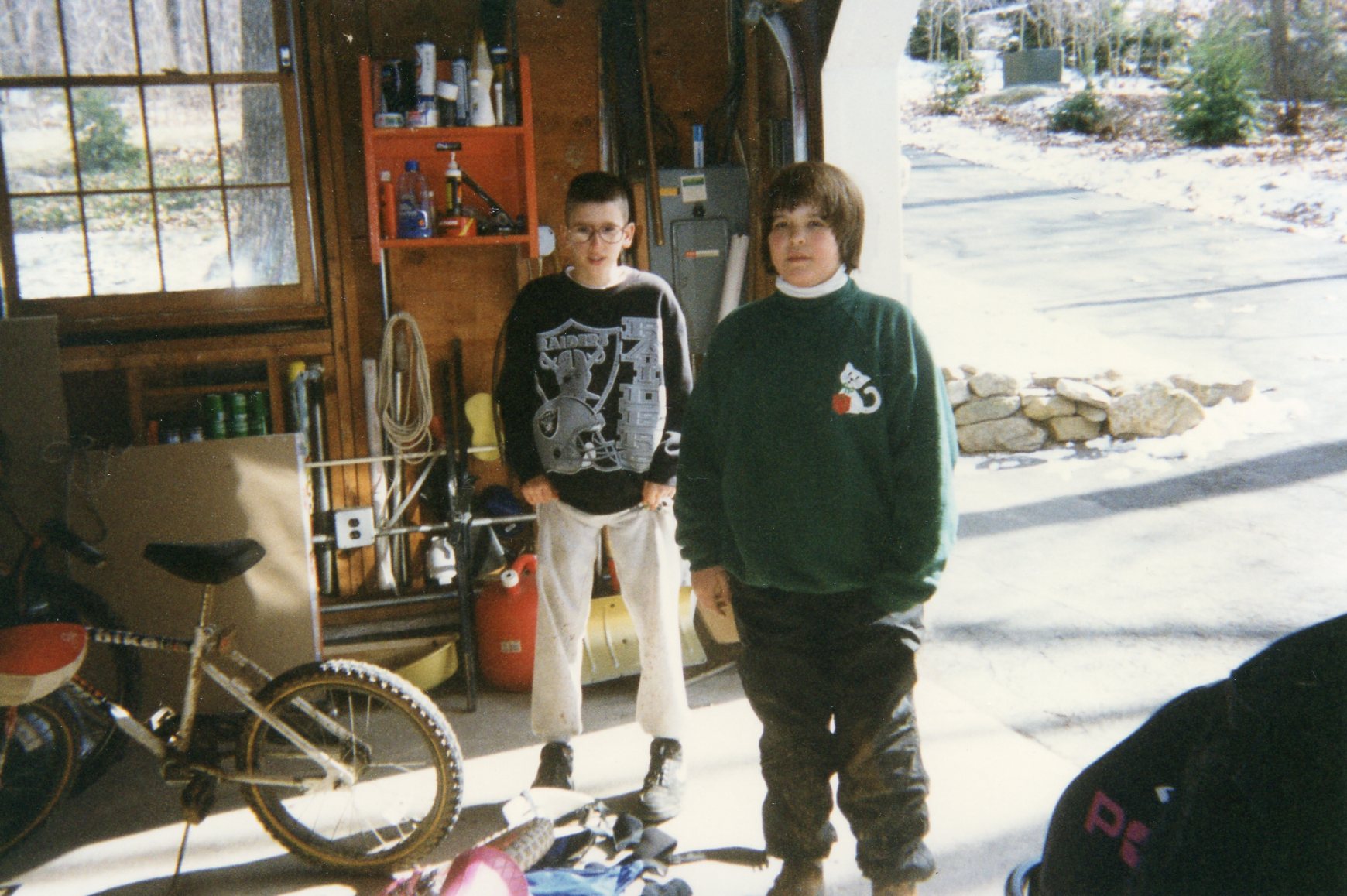

Bike repair time with Robert and Jenny.

Bike repair time with Robert and Jenny.

Other than my sister, there were two other kids in the neighborhood that I played with: Kevin Haney and Robert Spears.

Robert was a year younger than me. He lived two houses down the street, and our bike trail connected into more trails behind his house.

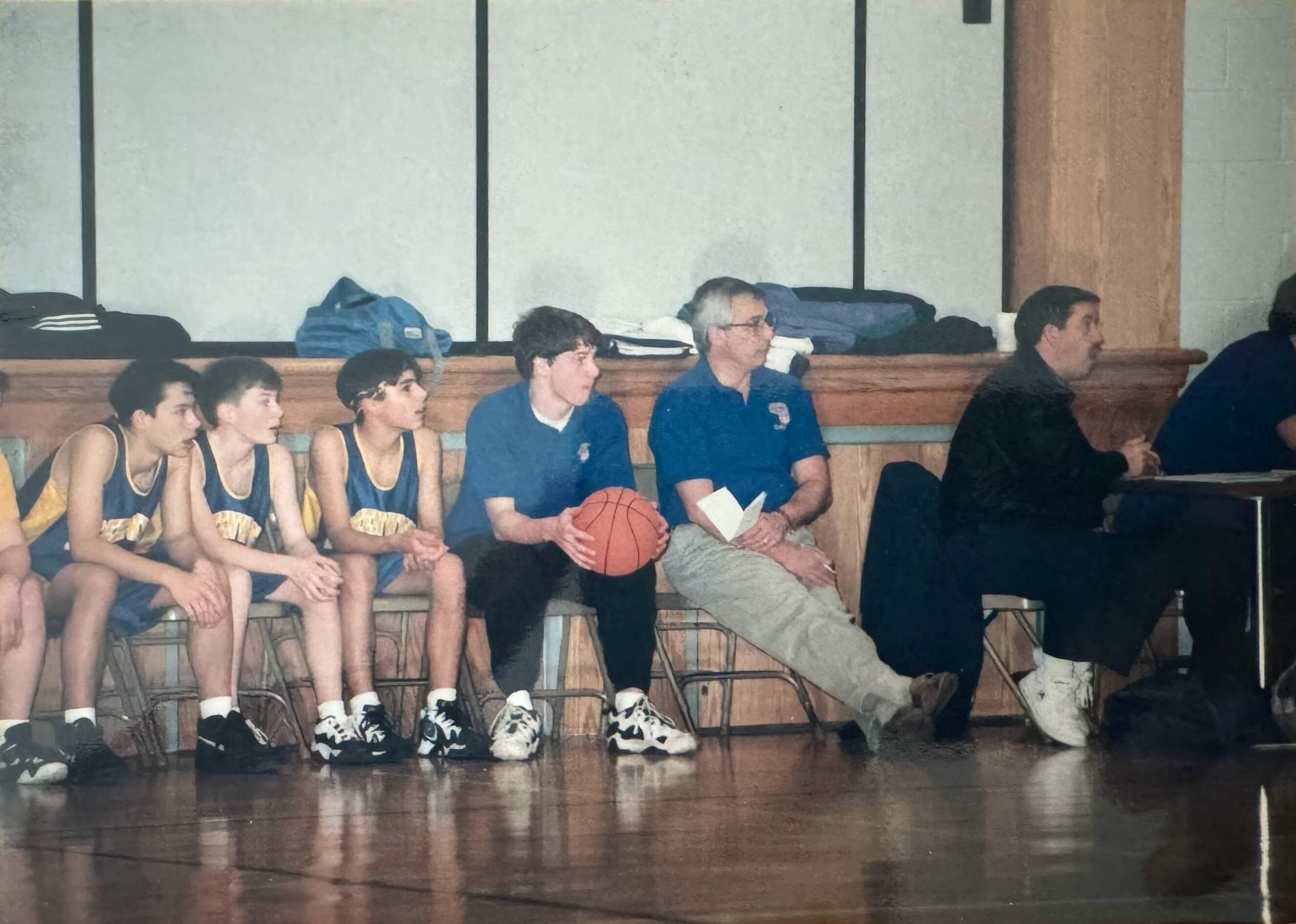

Kevin assistant-coaching my middle school basketball team.

Kevin assistant-coaching my middle school basketball team.

Kevin was two years older. He assistant-coached my middle school basketball team.

Kevin, Jenny, Robert, and I liked to play touch football in the street, but it was a little tricky to scrape together “fair teams” given our age and gender differences. If there were four of us, we usually split two on two, Jenny and me against Kevin and Robert. Sometimes my dad might step as an all-time-quarterback. The best scenario, however, was when one of us had a friend over, because then we could play two on two with Kevin as all time QB. But most of the time, there was only three of us to play.

There were also many days when it was just two of us – and of these, the ones I remember the most were the ones when it was just me and Kevin – cause I loved to “play up” two grades.

We usually played basketball – one-on-one (usually with odds that would give me a chance), twenty-one or twenty-one with tap backs, and HORSE or a variant on HORSE called MAZDA (inspired by the brand of Kevin’s dad’s pickup truck that parked in the driveway).

All of these were a ton of fun, but I actually don’t remember them as vividly as I remember our one-on-one wiffle ball games.

Wiffle ball bat, with backwards grip.

Wiffle ball bat, with backwards grip.

To fully appreciate our one-on-one wiffle ball games, you need to understand some very specific systems.

For example, we needed a system to define different types of hits – a home run fence, along with designated “hit zones” that qualified automatic singles, doubles, and triples. At Kevin’s house, there was a tree or a lumber pile in the back, and if you hit the ball over that it was a home run. There was a grassy area in right field for triples. And left field was pretty truncated with trees, so that was a double zone.

Now, suppose you hit a double – since there was only one person per team, this would put a “ghost runner” on second base.

Ghost runners operated by a second system of specific rules – eg, a ghost runner only advances if forced to – so, if you have a ghost runner on second, and you hit a single, the ghost runner on second would not push to third. Then, you’d have ghost runners on first and second, and then if you hit a home run, you’d score three runs.

Not every hit went to a hit zone, however – some hits got fielded “live.” Suppose you have ghost runners on first and second, and you hit a single to the pitcher. When the pitcher catches the ball, he then has several options:

(1) Throw the ball at the batter. If you hit him, he’s out, but the ghost runners would advance to second and third.

(2) Hit a “base target” at first, second, or third base BEFORE the batter reaches first base. This would get the runner going to that base out.

The system of base targets designated areas where an infield covered each base. At Kevin’s house, the first base target was a rock, second base was a tree, third base was a little gully at the top of the hill, and home base was a firewood cage.

If you threw at a base target and missed, there was a penalty, and each ghost runner would advance by one base, even if they were not forced.

Batter up.

Batter up.

Another system Kevin invented was the “batter lineup.” Each of us had a full lineup of nine distinct batters, each with a unique name and set of batting attributes.

Kevin had a batter Slammer Jammer. Slammer Jammer was really excellent at hitting pitches way inside the strike zone – so Slammer Jammer tended to really crowd the plate during his at-bats.

But there were also batters good at hitting outside balls that batted WAY away from the plate, batters who loved low pitches, batters who were good at stealing bases. (Stealing bases was another thing we had a system for, but I don’t remember how it worked.)

Another batter we both had batted with hands crisscrossed. Normally, a righty bats with left hand on bottom, and if you crisscross and put your right hand on bottom, you run the risk of breaking your wrists. I think (hope?), however, that this wasn’t a problem for us since the wiffle bats were extremely light weight.

If you think this whole batter lineup thing sounds excessive, you’re not wrong. But it’s also the kind of thing that made hours and hours and hours of one-on-one wiffle ball really fun. It made every game into a kind of story:

Slammer Jammer is on second base. You’re down by one in the bottom of the ninth, with one of your slugger batters at the plate…

Firewood cage “strike zone.”

Firewood cage “strike zone.”

We of course also had different pitchers each with unique specialty pitches, and at Kevin’s house, the same round firewood cage that we used as the home base target also served as our strike zone – if you pitched a ball inside this metal ring, it was a strike.

There were two really fun things about this.

Wiffle ball.

Wiffle ball.

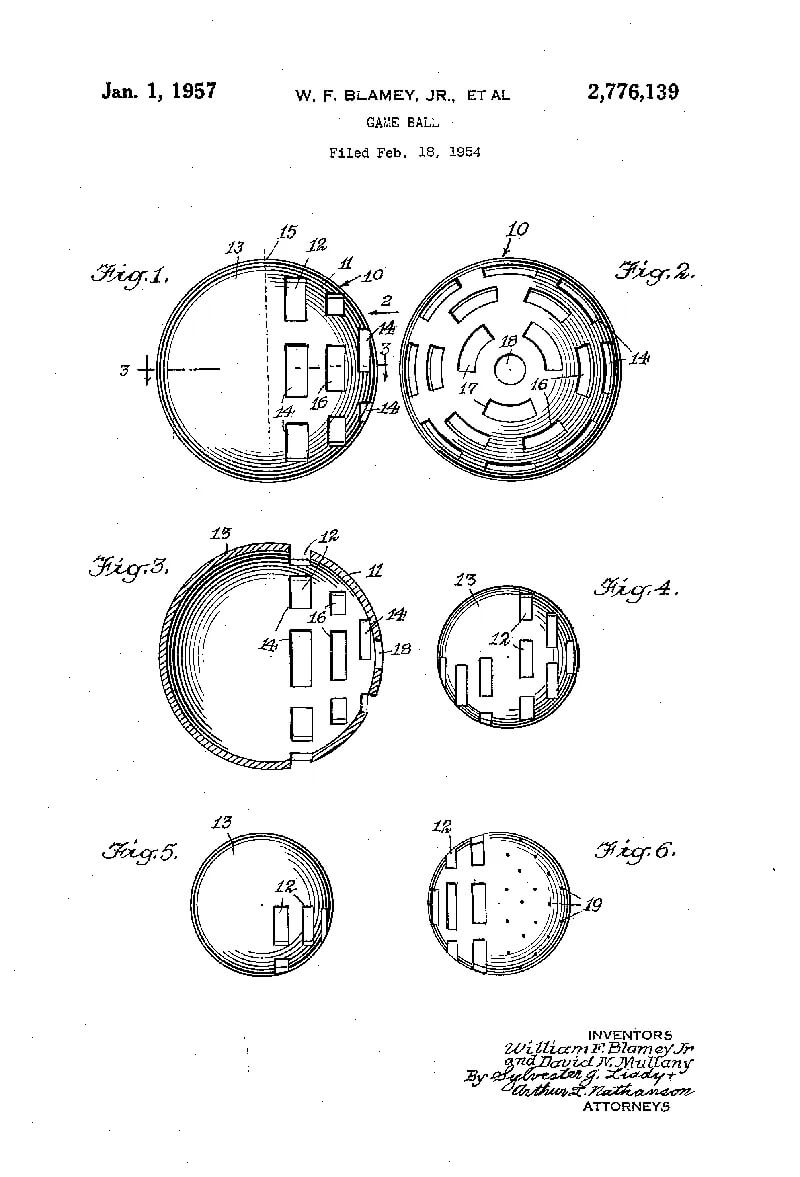

(1) We got VERY good at throwing crazy pitches using the slots in the wiffle ball – curve balls, sliders, knuckle balls, rising and falling pitches, rising and falling curves and sliders, etc. So, there was a whole game to trying to get the ball to be as far from the batter as it crossed the plate as you could while still getting the ball to ultimately land in the strike zone.

William F. Blamey, Jr. and David N. Mullany’s “Game Ball,” patented on January 1, 1957 U.S. Patent 2,776,139.

William F. Blamey, Jr. and David N. Mullany’s “Game Ball,” patented on January 1, 1957 U.S. Patent 2,776,139.

And (2) the ball did not even have to cross the plate in front of the batter. So, you could theoretically throw an extreme curve ball that landed in the strike zone but went BEHIND the batter This was an especially a good move if the batter batted way inside, like Slammer Jammer.

All these systems made one-on-one wiffle ball very, very fun.

Post-soccer handshake lineup.

Post-soccer handshake lineup.

As a kid, the team sport where I won the most MVP-type awards was soccer.

I found this picture of us doing our post-game lineup in the middle of the field where we’d shake hands and say “good game” to everyone on the other team. It’s the type of thing that sounds like a real “Sportsmanship™” poster when I say it out loud, but I can’t help getting a little emotional just looking the good vibes in this photo.

Third grade-ish soccer.

Third grade-ish soccer.

Early in my soccer career – about third through seventh grade-ish – I was really, really good at soccer. And although I was a good athlete, I think what really made me so “good” was that I could reliably kick the ball really hard. And when I kicked the ball really hard, this was just the right amount of power to put the ball in the top of the net. And when you’re young, the goal keepers had a hard time defending the top of the net cause they’re not that tall yet.

By the time I got into eighth grade, a really hard kick required a lot more aim to hit the top of the net, and goal tenders were taller, so I noticed a relative decline in my play.

In ninth grade, I moved to Georgia, and I was honestly a little worried I might not even make the high school soccer team in the spring. I’d spent all my fall afternoons practicing basketball, but then I only made the junior local traveling soccer team in the fall, and I didn’t even make the freshman basketball team that winter.

Santos traveling soccer.

Santos traveling soccer.

The spring soccer tryouts were a slog, but I did manage to make the team. In a recent conversation with an old friend I learned:

You didn’t make it because of your skill – it was your heart.

It was a dramatic departure from the MVP days of my youth. But I guess it’s kind of cool to think that one of the skills you can bring to a competitive team is a level of hard work that just raises the bar for all your teammates.

Cross Country, doggin it.

Cross Country, doggin it.

Pretty much my whole high school soccer team ran cross country in the fall to keep in shape, and even though I hated the “long-ish” one to two mile runs I had done to train for soccer, I signed up for cross country just to spend more time with my teammates.

Unsurprisingly, I didn’t love cross country – mostly because I had horrible running form. I wish I could go back and tell my high school self a few things about running:

(1) You don’t really “warm up” until you’re about a mile or two into a race. And don’t think that “warming up” is just a thing adults with tight hamstrings need to do!

(2) Don’t heel strike! Heel striking – where you land on your front heel – puts a ton of pressure on your ankle, knee, hips, and back. It’s why most people get hurt “running.”

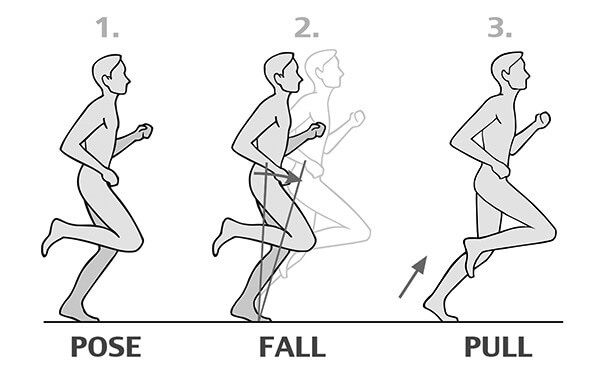

Pose running diagram.

Pose running diagram.

(3) Learn “pose running” instead – where you position your body to just fall forward and land on the ball of your foot with a bent knee. It’s so much softer on all your joints, so much more efficient!

I actually met a runner at an academic summer camp after my junior year of high school who tried to teach me pose running, but I bailed on it after about a hundred meters, because my calve muscles started killing me.

Five Fingers shoes with bloody shins from doing box jumps.

Five Fingers shoes with bloody shins from doing box jumps.

Sadly, I didn’t learn this calf burn was a natural (and brief) part of the learning curve until after college, when I got a pair of these Five Fingers shoes that forced me to land on the balls of my feet.

¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Cross Country race day.

Cross Country race day.

High school cross country practices began in July – the hottest, most humid time of the year. And once school started, practices moved to 330pm – the hottest, most humid time of the day.

We’d do hill workouts, distance runs, speed pace work, and speed ladder workouts where you work your way up – 400m, 800m, 1200m, 1600m – and back down the other side.

Many a 430pm I’d return from a hill repeat workout and stumble with a bunch of teammates to whatever water fountain in the school was closest. We’d take turns guzzling cold water for minutes, trying to cool down.

These brutal workouts weren’t as bad for me as race days You already saw the look of suffering on my face as I heel-striked my way through a course – and the funny thing is that the worst part of the race was not even the race itself – it was the anticipation of the race. At least during the race, every second you ran meant the end of your suffering was one second closer. But before the race, you didn’t have this mental countdown started – and I remember being literally nauseous with anticipation before each race began.

Putting yourself through all of this suffering – which was completely unnecessary and completely voluntary, btw – and doing it with a group of friends…

In retrospect, it was really special. It was almost like a cult. Our coaches made up for their lack of pose-running-knowledge with motivational speeches that inspired the crazy team spirit we all needed to just show up again the next day.

It was also really crazy – because in high school, I was chronically under-slept, in school all day, playing sports and doing all the intramural stuff after school, coming home late after night games, scarfing down dinner, then working for hours on whatever homework I had to get done for the next day…

Crazy – because high school is definitely the hardest I’ve worked in my entire life, and I’ve worked really, really hard most of my life.

It’s weird looking back on this now and wondering why I didn’t immediately quit cross country.

I came up with two answers.

The first answer is that just suffering, together, with a group of friends, is satisfying in itself. It bonds you, creates unity.

The second answer is a bit Sisyphean. It feels good to set a hard (but ultimately meaningless) goal and try to prove to yourself – and to no one else – that you can do it.

And if you can do that for something as meaningless as cross country, you can definitely do it for things you really care about.

thank you

Originally delivered as a talk for the MIT DEAL program in Aug 2024.