This is the strap of a backpack, which wore out from several years of everyday use.

The rest of the bag was in pretty good condition, and I really liked the backpack, so instead of buying a new one, I tried to get it fixed.

I took the backpack to several tailors, and they all said the strap was too thick for their sewing machines. They suggested taking it to a shoe repair place, where they would have machines that are heavier duty because they typically work with leather.

So I headed to Jacks’ Shoe Repair Service, where I’ve gone to get holes patched and re-soles done for a few pairs of sneakers.

I asked the guy behind the counter about the backpack. He looked at it kind of sadly, said almost apologetically, “I don’t think we can help you. I don’t have this material, I’d have to use leather.”

I don’t mind using leather.

“Well, the thing is, it’s just the cost.”

How much would it cost?

“Forty-five dollars. It’s not the leather. It’s just the time for the labor, you know.”

That’s fine, I like the backpack, and the rest of it is still in good condition.

“Well, you know, if we do it, I’ll also add some stitches to the bottom here where it’s starting to come apart a bit…..”

Forty-five dollars is five dollars more than the cost (to me) of buying the backpack new. This was a completely irrational transaction in terms of the dollar cost to me, but it would feel kind of grotesque to throw away a perfectly good backpack in need of minor repair in order to save five dollars.

I got to thinking about the economics behind this transaction.

First of all, the backpacks are manufactured in the Philippines and Jack’s Shoe Repair is in downtown San Francisco. Labor is far cheaper in the Philippines, and so is real estate. Both of these factor into the cost to me.

Next, consider the production process for making a new backpack vs the average process at Jack’s Shoe Repair. The factory production process for new backpacks is far more refined, goes through thousands more ‘reps’ of a uniform operation every day than Jack’s, where each day customers bring in different objects with different issues that require different, bespoke repair operations. The factory production lends itself to far greater specialization for each operation performed by a human, and the uniformity also presents a greater opportunity for machine automation.

Another feature of mass production which is related to (but distinct from) process refinement is the way it lends itself to QA. The factory can define a set of tests that measures when the new backpack is done and whether it meets quality standards. What’s more, the firm can take on the cost of this process and efficiently scale it. This means the firm can provide better guarantees that poor work will not reach a customer, which is more difficult to do at Jack’s Shoe Repair.

As a customer at Jack’s, unless you’re a regular, you might feel more at risk of being ‘burned’ by a local repair service than when you buy new from a large corporation. And, with a really intangible and complex service such as legal advice, you essentially have no way to verify ‘good work’ and no recourse when things go wrong. But, when material goods are the output of a production process, they can serve as ‘proof of work’ for the labor that went into them in a far more easily measurable way than with intangible services.

Yet another one of the nifty features of material goods is how they can serve as a durable store of the value of labor that allows it to move through space and time.

Consider food production, where stockpiling grains in a durable form makes us more resilient to natural disasters – like droughts, floods, blights, and fires – which would otherwise create food shortages by compromising crops.

For most of us here in California today, we’re not worrying about whether a fire next season is going to lead to famine, which is a testament to how well our society has taken advantage of this shelf life property.

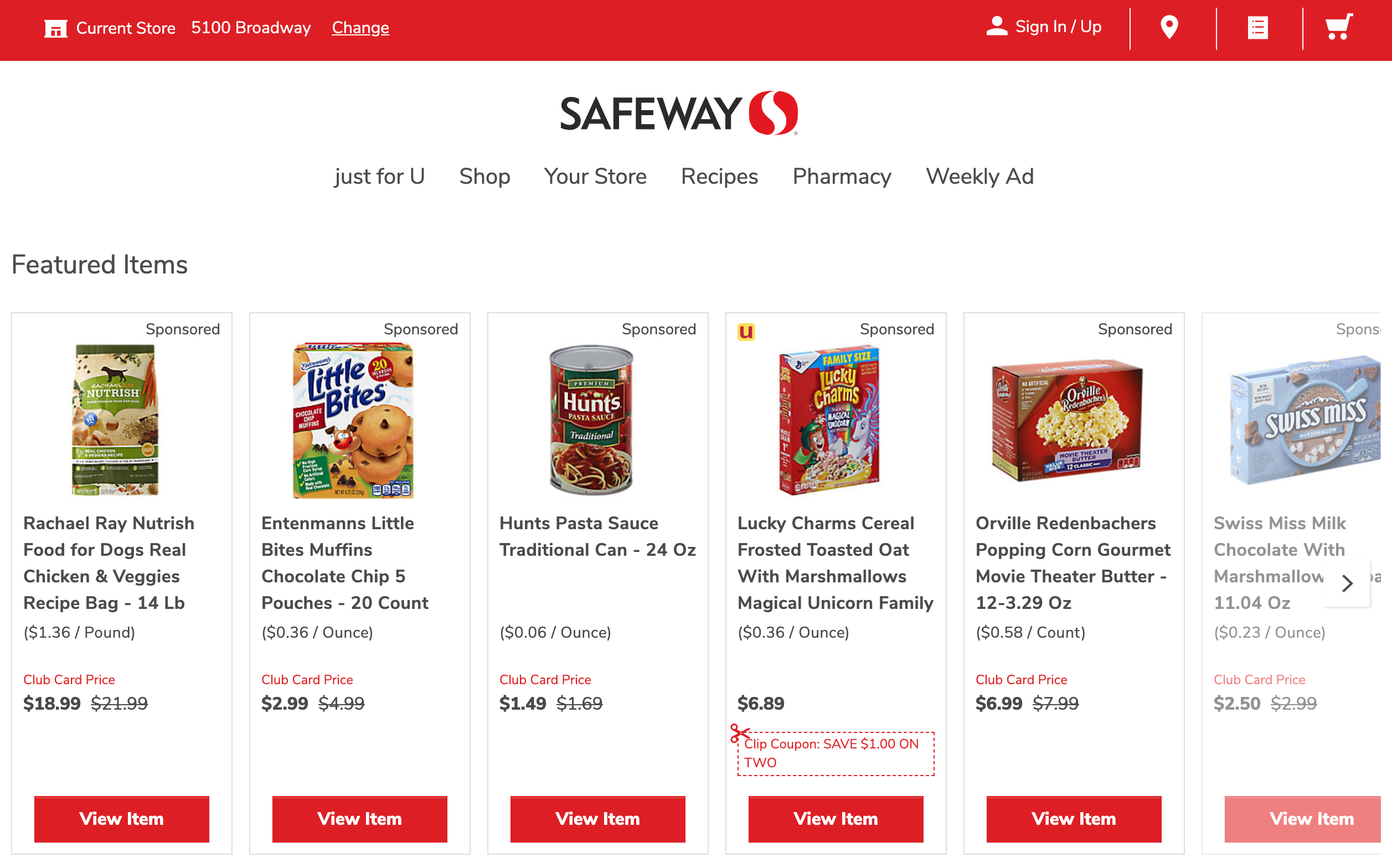

But, it is a similar optimization of inventory that explains why the grocery store is so tilted towards packaged goods, away from fresher items that have a much shorter shelf life – it’s just easier to stock preserved foods than to predict customer demand.

Now, consider a labor intensive services business – like Jack’s, or Starbucks. On-demand service is the ‘product’ with the shortest shelf life of all. (This is why services business are suffering so much so soon after the issue of ‘shelter at home’ policies.)

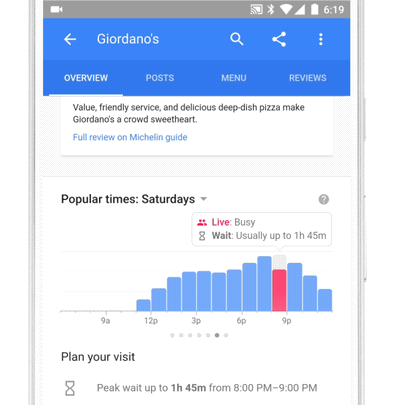

Whenever you ‘stock’ (or staff) an hour of human labor and customers don’t show up, you’re losing money. And every hour where there are more customers than workers can service, you’re losing business.

One way a place like Jack’s can handle a demand surge is asking customers to bear the burden, by having them drop off their shoes for repair and come back later. At Jack’s, this is not terrible (unless you need the shoes on your feet repaired immediately), but for other businesses – like a barbershop or restaurant – this may be less of a real option for customers.

Demand modeling, staffing to meet demand, yield management – all of these can get incredibly complex very quickly if you’re trying to deliver service with both low cost and low latency, and ultimately businesses will need to mark up the price of the service a bit to absorb some of the variance in demand by paying to have workers available and knowing they’ll go idle some portion of the time.

With durable material goods – ie, new backpacks – you have to worry far less about this supply and demand coordination problem.

So, we can explain why the brand new backpack is cheaper than the minor repair by looking at all of these ‘hidden efficiencies’ – and I put ‘hidden’ in scare quotes because they are sort of hidden from you as a customer at the counter at Jack’s Shoe Repair, not so hidden if you’re the one optimizing mass production.

Now, onto the hidden costs, which are very real.

Most of the hidden efficiencies ultimately all boiled down to minimizing the cost of labor in production as firms pursue profitability. Some of these – specialization of labor, innovative processes – are pretty pure efficiency wins with little externality (although you could argue the specialization of labor via repetitive process imposes the externality of a ‘boredom cost’ on the worker).

One cost of the new backpack (vs the repair) is the material resource waste. This is the main thing that makes the idea of a wholesale replacement over minor repair so grotesque, particularly when you think about how this trade scales up.

This photo (above) does not really look to me like a picture of efficiency.

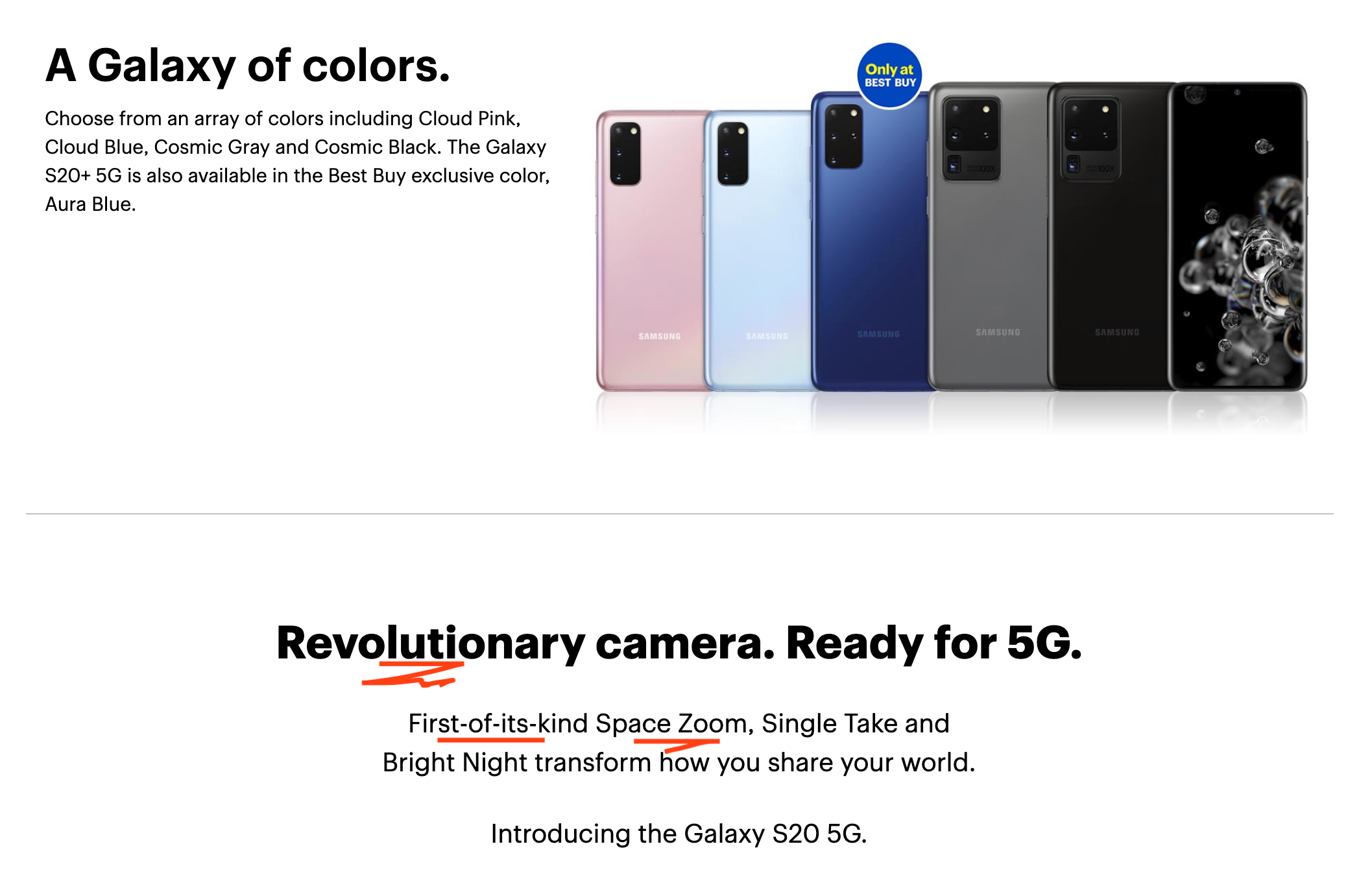

And, the profit motive is not simply about cost reduction – it is about profit maximization: the same incentive structure that rewards products with a long in store shelf life will reward products with the shortest possible lifetime and expiration after purchase. This is how you get the perverse phenomenon of planned obsolescence.

It’s also how you get things like ‘point release’ innovation features, new skins, fashion, etc. Perhaps the original iPhone was a revolutionary new product, but does a marginally better camera merit discarding an old version and upgrading to a new one?

The answer probably depends on how much disposable income you have and how much you care about photo quality – and maybe also how much you care about the signalling utility of a shiny new phone – but in any case, neither the manufacturer nor the consumer is bearing the full cost of material waste in the ‘upgrade’ transaction.

While consumer electronics are notorious for taking advantage of this tactic – I suppose because the veneer of innovation is built into the entire industry – you will see other industries which are less setup to exploit this upgrade cycle seize onto durability as part of their brand ethos.

The manufacturer of my backpack, for example, offers a sort of warranty, to communicate to me the alignment of their values with my own (for a durable product).

If you’re thinking about sustainability policy, one idea might be to require warranties like this one for all material objects. This would force companies to internalize the cost of goods that wear out quickly and incentivize them to create more durable products.

I had a hunch the manufacturer of my backpack would have some sort of warranty like this, so before I went to Jack’s Shoe Repair, I emailed to ask if I could ship the backpack to them for repair. They responded:

Typically we’d like to get those repaired so we can reduce, reuse, and upcycle those materials. However since [we] don’t have the tools and material necessary for a fix… I have included a $40 gift card code which is equivalent to the price of the pack when you purchased it back in 2017, feel free to use that towards the purchase of a new pack or another piece of gear from our website.

This is great from the perspective of my individual need for a functional backpack, but does not quite satisfy my demand for less material waste.

So, even when a warranty is in place and there is an incentive to create more durable products, due to all the efficiencies of material production, it still may be cheaper for the firm to produce the material waste and offer a replacement.

Perhaps moving upstream and tackling the demand side of the problem will offer some more feasible solutions…

A large amount of consumption is driven not by product wear and obsolescence, but by fashion, conspicuous consumption, and the positional signalling we are constantly doing through the products we buy.

On the one hand, it is tragic to think of the amount of waste generated by conspicuous consumption, but on the other hand, perhaps this presents an opportunity to eliminate a huge amount of waste from the demand side by shifting cultural values. What if for example, upgrading to the latest gadget or item from the fall line came to be regarded not as a sign of status, but as selfish and grotesque?

I was looking for historical examples of this sort of shift in cultural values, and one that came to mind was littering.

If you and I were walking down the street, and I just threw a phone I bought last year on the street like a piece of trash, you’d probably be shocked and say to me, “What the fuck is wrong with you? That’s not cool.”

And, yet you would probably not be shocked if I were to just create the garbage, upgrade to the new iPhone, buy the new jacket, use the plastic bottle, take the flight to Bali with a crazy carbon footprint that dwarfs that of all the consumables I’ll use this year just so I can take some exotic vacation pictures – you wouldn’t react the same way to all of these things.

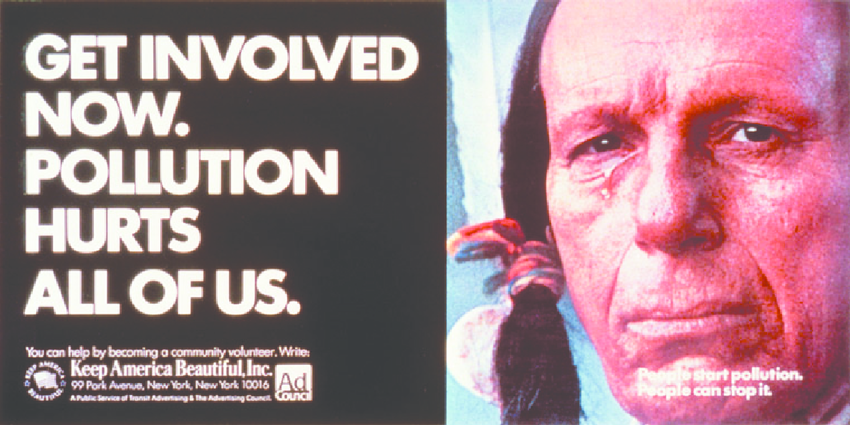

Did we always have this reaction to littering? I did a bit of research and learned about a non-profit called Keep America Beautiful, which was started in the 1950s. It ran public service announcement campaigns on litter prevention, waste reduction, and recycling, and did a pretty decent job of making littering morally unacceptable.

It was funded, however, by companies like Philip Morris, Anheuser-Busch, PepsiCo, and Coca-Cola, and it’s goal was to “confuse the public narrative regarding waste, and distract from the corporations and manufacturers creating the litter and waste” (wikipedia).

(Sigh.)

Update on this quote from Wikipedia which has apparently been removed due to lobbying...

Thanks to abjKT26nO8 on hacker news for digging into these wikipedia edits. Apparently, the original quote I had from the page was removed / re-added / removed a few times:

I looked for this part on the linked wikipage and didn’t find it. I looked at the edit history and it turns out that this wikipage is subject to a PR fight and the account DoBeautifulThings keeps removing parts that may be too critical and adding things that put it in a positive light. The source for the quote was this recording: https://www.npr.org/2019/09/04/757539617/the-litter-myth

Here is an edit from them that removes this part (2019-10-03): https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Keep_America_Beautiful&diff=919471408&oldid=919457645

A revert of the change (2019-10-03): https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Keep_America_Beautiful&diff=919473497&oldid=919471765

The change is back in (2019-10-04): https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Keep_America_Beautiful&diff=919612502&oldid=919473497

Another change that reverts some lobbying edits (2019-09-12): https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Keep_America_Beautiful&diff=915371004&oldid=914154035

If you want to see the wikipage version which contained the quote, here it is: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Keep_America_Beautiful&oldid=919473497

Lobbying on Wikipedia is real.

I was first researching Keep America Beautiful in Sep 2019, so this makes sense.

I tend not to be a conspiracy theorist because I think they usually give too much credit to large institutions and overestimate their competence in execution, but this story might qualify as my favorite actual conspiracy theory from history. Of course the only example I can think of for a cultural shift towards more sustainable values turns out to be the result of profit motivated corporate lobbying and advertising.

I can see why many people give up in despair.

Up next, the rest of this essay in 2 more parts:

Subscribe to get notified when I post more essays.