The Dying Achilles, Ernst Herter

The Dying Achilles, Ernst Herter

When Odysseus visits the kingdom of the dead in Book 11 of The Odyssey, he comes upon Achilles, greatest of all the Greek warriors who fought in the Trojan War, and he congratulates the hero:

Time was, when you were alive, we Argives

honored you as a god, and now down here, I see,

you lord it over the dead in all your power.

So grieve no more at dying, great Achilles.

Achilles immediately dispels any illusions:

No winning words about death to me, shining Odysseus!

By god, I’d rather slave on earth for another man –

some dirt-poor tenant farmer who scrapes to keep alive –

than rule down here over all the breathless dead.

This is one of my favorite bits of poetry, and I used to think this passage from The Odyssey represented a revision of the attitude toward glory Homer takes in The Iliad, where Thetis pleads with Achilles not to take the battlefield, laying two fates before him:

Mother tells me,

the immortal goddess Thetis with her glistening feet,

that two fates bear me on to the day of death.

If I hold out here and I lay siege to Troy,

my journey home is gone, but my glory never dies.

If I voyage back to the fatherland I love,

my pride, my glory dies …

true, but the life that’s left me will be long . . .

Achilles ultimately ignores the pleas of his mother and returns to battle with full knowledge of this prophecy – evidence, I thought, that he regards the short, glorious life as more virtuous than the long, domestic life.

Homer’s reversal is a favorite talking point of mine, and I’ve had the passage from The Odyssey saved in a notebook for years. My only reference to The Iliad was Thetis’ prophecy – which is a bit lackluster – so I finally decided to hunt down an equally beautiful passage celebrating war and glory in The Iliad.

I was surprised how difficult it was to find what I was looking for.

I remembered discussing the passage from The Odyssey with one of my college professors – Anne Hall – and I thought she might have ideas on where to look in The Iliad, so I emailed her. She replied with a few contradictory passages and said:

One cannot find in The Iliad a clear stance on anything….

A little concerned I’d been peddling a bogus theory for over a decade, I did some more digging.

When Achilles finally accepts his fate and decides to re-enter the battle, he does say “for the moment, let me seize great glory,” but the brunt of his speech in this climactic moment suggests that his primary motivation is not glory, but guilt:

Since it was not my fate

to save my dearest comrade from his death! Look,

a world away from his fatherland he’s perished,

lacking me, my fighting strength, to defend him.

But now, since I shall not return to my fatherland …

nor did I bring one ray of hope to my Patroclus,

nor to the rest of all my steadfast comrades,

countless ranks struck down by mighty Hector –

No, no, here I sit by the ships …

a useless, dead weight on the good green earth –

And far from celebrating the battle, Achilles laments that gods and men alike cannot seem to escape violence and the anger that motivates it:

If only strife could die from the lives of gods and men

and anger that drives the sanest man to flare in outrage –

bitter gall, sweeter than dripping streams of honey,

that swarms in people’s chests and blinds like smoke –

If anything, The Iliad is a warning against the pursuit of glory on the battlefield.

Where, then, does virtue lie?

For one answer, we can look again to Achilles, as he prepares to enter battle:

Now, by heaven, I’ll arm and go to war.

But all the while my blood runs cold with fear –

Menoetius’ fighting son … the carrion blowflies

will settle into his wounds, gouged deep by the bronze,

worms will breed and seethe, defile the man’s corpse –

his life’s ripped out – his flesh may rot to nothing.

Achilles stares, unflinching at the fate that awaits all warriors – and all men, eventually – death and a corpse that rots to nothing. And his “blood runs cold with fear.”

Yet – despite his wish that war (and death) would die, despite his yearning for a long life in the fields, and maybe even an eternal one – he does not turn away. He accepts his fate, putting his duty to his friends and countrymen above his own desires.

Man Push Cart, Ramin Bahrani

Man Push Cart, Ramin Bahrani

Every once in awhile, I get asked to speak to a group of students – like the Northeastern University Entrepreneurs Club – and I think, Why is it always an entrepreneurs club? The only thing anyone seems to think I’m qualified to talk about is business…

Ah, but for years, you yourself missed the point of The Iliad. “No winning words about death to me, shining Odysseus…”

It’s not that I’m against business, or entrepreneurship – to the contrary, I’ll often go out of my way to support a small business rather than shopping at a global mega-corporation. We could use more small businesses, in my opinion.

What makes me uncomfortable, I suppose, is that there is a certain agenda or expectation that I read between the lines of any invitation – that there’s a set of institutions and cultural mores that my career would suggest that I will endorse – that I’ll inspire others to work within a framework where a particular set of values is implicit.

How to Start a Startup Lecture 5: Competition is for Losers

How to Start a Startup Lecture 5: Competition is for Losers

The aptly titled Competition is for Losers Lecture 5 of the Stanford CS 183B class How to Start a Startup offers this advice to aspiring startup founders:

[I]f you’re starting a company, if you’re the founder, an entrepreneur starting a company, you always want to aim for monopoly, and you want to always avoid competition….

[T]the basic idea of when you start one of these companies [is] how do you go about creating value? And this question, what makes a business valuable? And I wanna suggest that there’s basically a very simple very simple formula – that you have a valuable company if two things are true. Number one, that it creates X dollars of value for the world. And number two, that you capture Y% of X.

I don’t think this is the wrong strategy.

And the bold honesty is refreshing. Most conversations venture capitalists deploy turns of phrase like “competitive moat” or “defensibility” or “network effects” or “proprietary algorithm” or “race to capture the market” or “intellectual property” – all of these are really just code for “monopoly” that can both put your own conscience at ease and maybe even slip past the cautionary ears of your in-house general counsel, saving you a few stern attorney-client-privileged reprimands (but don’t bet on this if your GC is any good).

Stonks Only Go Up, makeameme.org

Stonks Only Go Up, makeameme.org

If your goal is profit – and as an entrepreneur, your goal (and your fiduciary responsibility to your shareholders) is to maximize profits – then, indeed, “competition is for losers,” because competition sucks all the profits out of a market.

The simplicity is clarifying, and it’s part of what makes capitalism so successful. But, as with many things, the greatest strength is also the greatest weakness.

We yearn for ways to reduce complexity, and business promises us a clear definition of value that we can then break down into all sorts of KPIs and metrics for success we can optimize – it’s all very seductive.

And it works – if you constrain your field of view to the right spreadsheet. But, this entails closing your eyes to what we fondly call “externalities” – things like pollution or environmental impact or public health or human dignity.

But wait, you’ll say, what about positive externalities? And doesn’t a rising tide lift all boats?

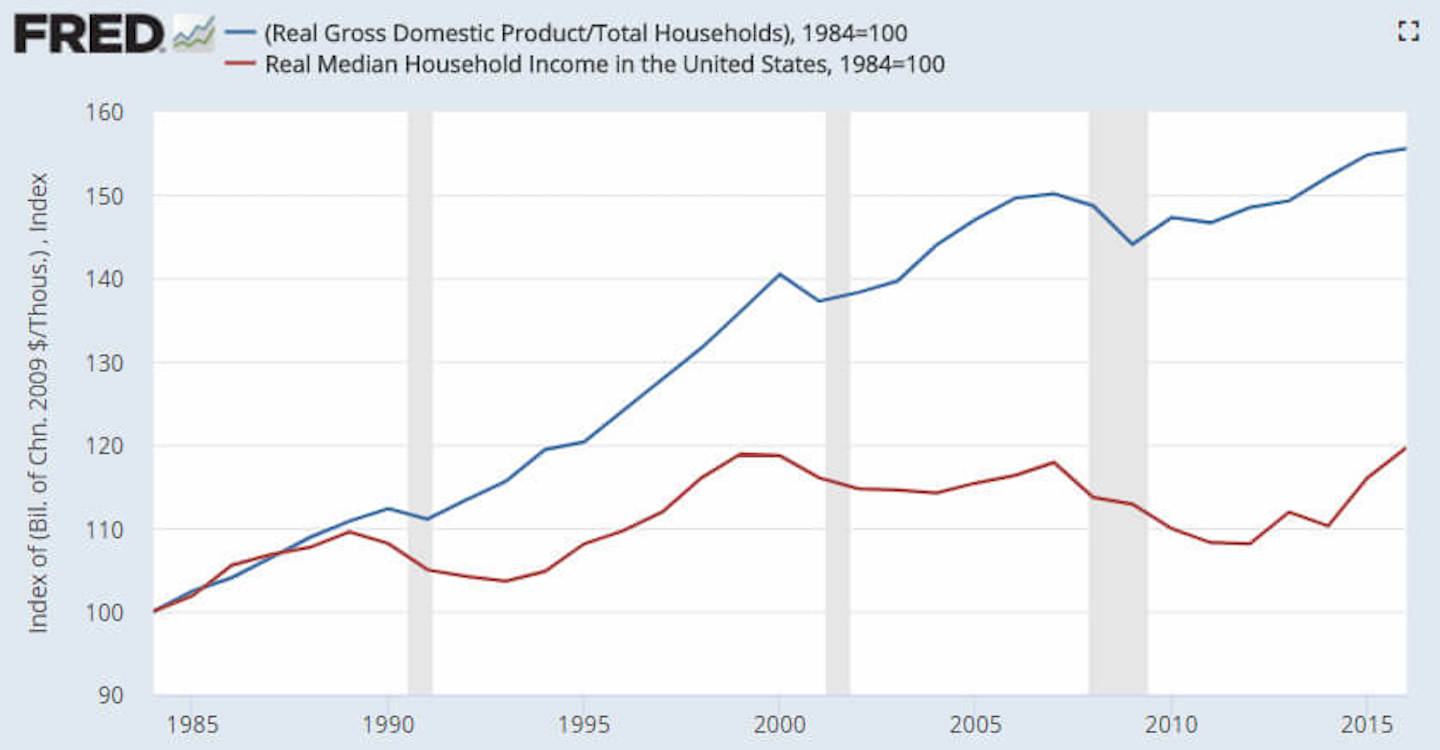

One of my favorite illustrations of the rising tide lifting all boats is this chart comparing US Median Household Income with Per Capita GDP:

US GDP per capita vs median household income

US GDP per capita vs median household income

It shows two ways you might define “all boats.” (1) The “average boat” / GDP per capita (or per household) GD. (2) “most boats” / median household income.

I like to always remember this chart the way Achilles recalled unflinching the image of the carrion blowflies and worms seething in the rotting flesh of Patroclus’ corpse.

Another myth is dispelled, and it’s back to the old questions. I suppose this is why Anne Hall retains such a place of reverence for me.

I first met her in the fall of 2004 when I took her class on Poetry and Political Philosophy in Ancient Greece.

Her syllabus suggested we direct our reading, discussion, and writing with the following questions in mind:

The questions we will be asking about The Iliad will persist throughout the course. What is human happiness? What is human wisdom? Wherein lies human dignity? What political arrangements address these notions of dignity, happiness, wisdom?

Who Still Believes in the American Dream?, Chris Arnade

Who Still Believes in the American Dream?, Chris Arnade

“Wherein lies human dignity?” A great teacher knows how to ask great questions, and the questions from this syllabus are worth asking not just of the poetry and histories of ancient Greece, but also of all the literature and art and film and music you encounter.

And they’re worth asking of yourself.

And they’re difficult to answer – especially when you are honest – especially when you know deep down you don’t like your answer.

But asking great questions is asking hard questions. One of my old computer science teachers, Max Mintz, used to slip unsolved math problems into our homeworks, for example.

“Wherein lies human dignity?” is kind of like that.

I used to think that there was some sort of “right” answer to this question – or, rather, that there was some sort of argument or rational line of thinking that would justify some of the things we intuitively consider good or dignified – and – like so many other discoveries of science – the formulas explaining the true nature of things were just not broadly known.

That may sound naive to you – but is it any more naive than accepting the assumptions built into the dominant cultural definitions of “success” and “progress” and “fairness” without doing a rigorous and honest analysis?

Tout est pour le mieux dans le meilleur des mondes possibles – Candide

A clever retort here might proceed as follows: perhaps these dominant cultural values emerged from the absence of any firm answer. Our broadly agreed upon values bow to the limits of human understanding. Far from naivete, this represents a pragmatic embrace of reality.

Perhaps.

It was this sort of response, I think, that motivated the urgency of Anne Hall’s teaching.

The journalist Frank Bruni – also a student of hers – wrote an op-ed arguing that “in a democracy, college isn’t just about making better engineers but about making better citizens,” where he remembered her urgency with reverence:

I saw a woman named Anne Hall swooning and swaying as she stood at the front of a classroom in Chapel Hill, N.C., and explained the rawness and majesty of emotion in “King Lear.” I heard three words: “Stay a little.” They’re Lear’s plea to Cordelia, the truest of his three daughters, as she slips away. When Hall recited them aloud, it wasn’t just her voice that trembled. It was all of her.

I remember her speaking with the same gravity when she recounted how Priam begged Achilles for the body Hector with the unimaginable grief of a father who outlives a son – how this grief evoked such compassion from Achilles that he agreed to return the body of Hector – the man who had slain his best friend – to the the grieving Priam.

And I remember when a flippant student dismissed the possibility of a serious conversation about an idea as romantic as human dignity with a Postmodern scoff. I saw this deep sorrow in the eyes of Anne Hall – ah, dear child, I know it’s difficult, but do you not grasp the implications of the nihilism you are embracing?

Le Rayon Vert, Eric Rohmer

Le Rayon Vert, Eric Rohmer

When you give up on the idea of human dignity, it is easy to land in cynicism, nihilism, madness, despair – any of which might be a sort of perverse relief from the soul-wrenching, hopeless search for answers.

Anne Hall understood that she was leading us to the brink of the abyss – where the natural response was fear and trembling – where it was easy to lapse into nihilism and despair.

And yet…

If you have not walked here, how can you have confidence in your own beliefs and actions?

If you have not walked here, how can you aspire to help others?

If you have not walked here, how will you earn the respect of those who have asked these questions with unflinching honesty?

There’s this refrain in Cormac McCarthy’s The Road about “carrying the fire” – the boy asks a stranger he encounters on the road:

How do I know you’re one of the good guys?

You dont. You’ll have to take a shot.

Are you carrying the fire?

Am I what?

Carrying the fire.

And it’s really not that complicated – you know – this imagery of light and darkness. It’s kind of childlike – and I think that is part of the point.

For me, “Are you carrying the fire?” is like “Wherein lies human dignity?” – a kind of shorthand, a set of neurons that fire with a host of associations – light and being one of the good guys and refusing to submit to nihilism.

So I’m always sort of asking people I meet if they’re carrying the fire – not in these words – but asking if they’ve confronted the darkness – because I think honestly confronting the darkness and refusing to dismiss such confrontation as naivete is a sort of prerequisite to being one of the good guys. And I’m trying to find the good guys.

A few weeks after I graduated from college, I was having tea with Anne Hall, and she said to me:

I was about your age when I realized that I was not going to have enough time to do all of the things I wanted to do in life…

Imagine how quickly whatever remained in my memory of the commencement speech I heard a few weeks earlier must have disappeared in the face of the gravity and honesty of this chat, over tea.

I respect people who don’t shy away from the truth in conversation, in art – because it implies a respect for me and my ability to handle the truth, however tragic it may be.

“No winning words about death to me, shining Odysseus!”

No Time for Despair Toni Morrison mural, Pasteur Mudende

No Time for Despair Toni Morrison mural, Pasteur Mudende

Ah, all this talk of death and despair and nihilism – tragedy, is I guess the name for it – I appreciate the honesty, but it’s kind of depressing – and these days what truly inspires me is when I find someone who has gazed into the abyss and emerged with a light step. Consider Toni Morrison:

Good is just more interesting, more complex, more demanding.

Evil is silly. It may be horrible but at the same time it’s not a compelling idea. It’s predictable. It needs a tuxedo; it needs a headline; it needs blood; it needs fingernails; it needs all that costume in order to get anybody’s attention.

But the opposite, which is survival, blossoming, endurance – those things are just more compelling intellectually, if not spiritually…

She’s saying, Yea, I know there’s not really a good argument for being good and not being evil, but I’m gonna give you one anyway. And her matter of fact justification is a pretty good one. Good is “more interesting, more complex, more demanding.” Evil is “silly” and “predictable.”

I love imagining Toni Morrison making one of those what I like to call “MBA spreadsheets” where you list – in neat columns – the pros and cons of your options when making a difficult decision. And I smile, because she is probably the only person in the world who would put “more demanding” and “more complex” in a pros column and “predictable,” “headlines,” and “attention” in a cons column – completely alienating the marketing people, the finance people, the ops people, the engineering people. Pretty much everyone would balk.

And any government these days would, too.

“More complex, more demanding” – we need something easy, something that scales! We can’t possibly “demand” something from our citizens – we need to be thinking of them as customers! Especially when the other guys are promising to give away everything for free and saying it’s gonna be a completely frictionless experience!

The skeptics aren’t exactly wrong – it’s difficult – if not impossible – for democracy to be demanding. David Foster Wallace devotes a brilliant chapter to this paradox in The Pale King:

There’s something very interesting about civics and selfishness, and we get to ride the crest of it. Here in the US, we expect government and law to be our conscience. Our superego, you could say. It has something to do with liberal individualism, and something to do with capitalism…. We infantilize ourselves. We don’t think of ourselves as citizens – parts of something larger to which we have profound responsibilities. We think of ourselves as citizens when it comes to our rights and privileges, but not our responsibilities. We abdicate our civic responsibilities to the government and expect the government, in effect, to legislate morality…..

…. As citizens we cede more and more of our autonomy, but if we the government take away the citizens’ freedom to cede their autonomy we’re now taking away their autonomy. It’s a paradox. Citizens are constitutionally empowered to choose to default and leave the decisions to corporations and to a government we expect to control them. Corporations are getting better and better at seducing us into thinking the way they think – of profits as the telos and responsibility as something to be enshrined in symbol and evaded in reality. Cleverness as opposed to wisdom. Wanting and having instead of thinking and making. We cannot stop it. I suspect what’ll happen is that there will be some sort of disaster – depression, hyperinflation – and then it’ll be showtime: We’ll either wake up and retake our freedom or we’ll fall apart utterly.

bed bath beyond, google image search

bed bath beyond, google image search

And we’re back to the question from Anne Hall’s syllabus: “What political arrangements address these notions of dignity, happiness, wisdom?”

This is one I think a lot about these days – I guess because I think our current political arrangements leave a lot to be desired in terms of fostering dignity, happiness, and wisdom.

I suppose a similar thought was one of the draws to entrepreneurship – there’s this story you might tell yourself, that big government and big corporations are corrupt and bureaucratic – but the real power today lives with corporations, with money – so if you want to change the world, you should start a new kind of company – free of all the baggage – and seize the power to do things differently.

Sequestered Carbon Sunglasses, Pangaia

Sequestered Carbon Sunglasses, Pangaia

A few weeks ago, I went to go see some talks by this couple in their early 60s. Her talk was on the DIY construction of off the grid homes, his on farming. Thanks to my misreading the timing of her talk and a lack of sufficient attendance to make his talk happen, I ended up just having a more casual conversation with the two of them – about climate change, water usage, solar energy production. It was so wonderful talking to these people from a different generation, who shared a set of concerns about the future, who had been getting their hands dirty and practically taking action.

It was invigorating – and towards the end of our chat, I asked what inspired them, what gave them energy to keep fighting the good fight despite the odds.

And the gentleman proceeded to gush about how he had seen a story about these sunglasses made from carbon sequestered from the atmosphere that cost $400 and when they debuted, they immediately sold out – proof, he said, that people were more aware these days, and willing to spend exorbitant amounts of money on sunglasses to show they cared. Things were changing.

A little shocked that this was his answer, I said I didn’t really find that story very inspiring. He asked why. I said, I don’t think we are going to shop our way out of climate disaster. Hard things are hard.

The woman came to his defense with the same pragmatism of the story you might tell yourself about entrepreneurship – this is how the world works and if you’re serious about saving it (the world) you need to embrace it and abandon your naive idealism.

We were about out of time at this point, so I couldn’t explain – I understand your pragmatism. I told myself the same story, the story I heard in school and in TED Talks. I’m not just another idealist who wants to go backwards, return to the good old days – where we all live on self sufficient little plots of land, don’t rely on the power grid or public infrastructure for anything, live ecologically in harmony with nature, yet retain all the fruits of technology and capitalism.

I know that hard things are hard – not the least of which is expecting people to rise to the occasion, to endure sacrifice, to participate in the change themselves.

So much easier to imagine we can to make it easy and frictionless for them – and to say this is our only hope, because this is how our world works.

The problem is this is short sighted. Maybe you will scale your strategy – your business – faster than something more difficult – something more distributed or democratic – but the more successful you are, the more you begin to adopt the principles that today govern the world – profit maximization, hierarchical power structures, manufacture of false scarcity, demand generation.

There’s an undertone of austerity in “hard things are supposed to be hard” – I know. And maybe asking people to sacrifice personal comfort for some sort of greater good limits their freedom.

But I’m not so sure how much freedom we really have today. Sure, you are free to buy whatever you want, but billions of advertising dollars are spent every year training you to desire certain products – so can you even be sure you have freely chosen what you desire today?

And how much choice do you really have at a fundamental level – for example, is the option of a 10-hour work week really on the table – how much would you trade to live in that world?

How would you spend your time? You’d get back 75% of it – still, maybe not enough to do all the things you want to do in life, but you could do a lot more.

For Anne Hall

What is human happiness? What is human wisdom? Wherein lies human dignity? What political arrangements address these notions of dignity, happiness, wisdom?

I wanted to write something for Anne Hall – to thank her for asking these questions, for meticulously wording these questions, for caring about these questions, for communicating the urgency of these questions, for respecting my ability to grapple with these questions, and for reminding me to always investigate the implicit answers to these questions that are embedded in all of our social relations.

What’s funny is, I’m not sure she will approve at all of what I’ve said.

Her Directions for English 359 - The Tide and Seawood of History (Spring ‘05) begin with this guideline:

An introductory paragraph should state the thesis you are going to argue in the paper…. Discovering your thesis is the hardest part of your paper. It should be a thought that, in the first paragraph, is stated at a high level of abstraction, so high that it may be unclear.

I definitely do not have an introductory paragraph. Is there even a thesis here? If there is one, I don’t think anyone would say it has been clearly stated or argued – evidence, I suppose, that I’m still hoping to discover my thesis.

At the very least, I hope she appreciates my improved understanding of The Iliad.

At the risk of saying absolutely nothing in nearly five thousand words, I’ll conclude by telling you what interests me and how I’m spending my own time trying to do some of the things I want to do in life.

In The Philosophical Baby, Alison Gopnik writes:

Rules allow us to perform complex, coordinated behaviors – they let us help other people in new and powerful ways. But intimate, emotional empathy is a force that can change even the most entrenched rules. If we discover that a rule leads to harm rather than good we can reject that rule. This is especially true if we experience that harm in the rich, intimate way that comes from interacting face-to-face with a real person in real life.

….

Often a return to the intimate empathy of infancy – that immediate sense of how other people feel – can be the most powerful way to change what people do. For example, we dehumanize people in the “out-group” – people who are not like us. This impulse is deep-seated and very difficult to overturn completely. One of the best ways to change it is to actually become intimate with the out-group – to recognize that those people are actually like me. People who come to know someone well who is openly gay are much more likely to support gay rights. Individual stories are powerful agents of moral change – often more powerful than rational arguments.

I appreciate the power of rules that govern the world today, I appreciate the good they have made possible, but I am increasingly convinced they are doing more harm than good – not only to the environment, but to human dignity.

I am also increasingly convinced that rational argument – though maybe necessary as a justification motivating change – will not be sufficient to motivate the change we need.

So I am interested in compassion – because my notion of dignity is inseparable from compassion.

I’m interested in compassion, because I agree with Gopnik that compassion and empathy can change even the most entrenched rules.

And I’m interested in individual stories, because they have the power to evoke compassion.

So I suppose I just hope that my meandering stories about Anne Hall can maybe move things a little bit in the direction of compassion. Her questions have undoubtedly given me a framework for expanding my own compassion, and I hope that posing them to you gives us a better shot at discovering political arrangements that are more aligned with dignity, happiness, and wisdom than those that exist today.

Thank You!

Links:

- Homer, The Odyssey

- Homer, The Iliad

- Arnade, Who Still Believes in the American Dream.

- Voltaire, Candide

- Bruni, College’s Priceless Value

- Kierkegaard, Fear and Trembling

- McCarthy, The Road

- Mudende / Morrison, No Time for Despair

- Morrison, interview

- Wallace, The Pale King

- Gopnik, The Philosophical Baby